Welcome to this edition of our Tools for Thought series, where we interview founders on a mission to help us think better and make the most of our mind. Heiko Haller is the co-founder of Infinity Maps, a tool for visual thinking and knowledge sharing that lets you create deep knowledge maps to manage information overload and collaborate on complex ideas.

In this interview, we talked about the unique challenges faced by knowledge workers, the limitations of mind maps and concept maps, the importance of structure, hierarchy, interconnectedness, and scalability, the difference between “finding” and “reminding”, and much more. Enjoy the read!

Hi Heiko, can you start by introducing yourself and give a bit of background about your interests? I saw that you studied computer science and psychology, that sounds fascinating.

I have always been passionate about creating brain-friendly learning media. I nearly studied media technology, but then I thought that I would learn the technical side by myself, so I studied psychology to better understand the brain and design brain-friendly knowledge media.

I then widened my focus to thinking tools and visualization tools. I studied existing methods and had the idea of combining the benefits of all of these methods. That was the topic of my PhD in computer science, where I was able to make a proof of concept.

I have also worked as a consultant for startups and automotive companies, which makes me one of these people who can bridge the cultural gaps between business, technology, and the human side of product design — I speak all three languages.

Between your studies in psychology and computer science, and your work as a consultant, you probably understand quite well the challenges faced by knowledge workers.

There is a great quote by Peter Drucker that goes: “The most important, and indeed the truly unique, contribution of management in the 20th century was the fifty-fold increase in the productivity of the manual worker in manufacturing. The most important contribution management needs to make in the 21st century is similarly to increase the productivity of knowledge work and the knowledge worker.”

But he also adds that the methods to achieve these goals are totally different because manual work and knowledge work are completely different fields. To address the challenges of knowledge workers, like researchers, consultants or students, you need to have a much stronger focus on the psychology of work and on how the brain works. You need to ask yourself: what gets in the way of us thinking really complex or complicated topics?

One of the most basic challenges is that our working memory is very limited — you can compare it to the RAM of a computer. It can only hold like a handful of thoughts at once. We can’t think about many things simultaneously, and that becomes a real problem when we deal with complex topics like we are faced with nowadays.

Another major limitation is that we are often unable to recall certain things. The good news is that our long-term memory is practically unlimited. There’s no lack of space in our long-term memory. When we have forgotten something, it’s not because it’s out of our memory, it’s just that we can’t find a way to get there.

Many knowledge workers have tried to solve these problems using mind maps or concept maps, what do you think about these?

Mind maps have been proven to be really useful whenever we need to deal with more than a handful of things that we want to juggle, for example if you want to do a brainstorming session and then sort these ideas.

When things get too many to grasp, we put them in boxes and we create hierarchies. If you think about geography, we have the solar system, the planets, continents, countries, counties, cities, blocks, houses, flats, rooms.

That’s why we are so used to using folder hierarchies on our laptops. It’s natural for us to think in terms of things that are in other things. We never look at the whole scope. We always focus on a certain level. That’s one major thing that mind maps really cover in a nice way.

What mind maps are bad at is to show how things interact, or what are the interconnections between topics — for example, this leads to that, and that contradicts that over here — because these relationships are simply not hierarchic and they don’t fit in a mind map.

In contrast, concept maps are great for showing interrelations. They are graphs, they are networks. They have nodes and edges. They show not only how things belong together, but also how they interact. But, contrary to mind maps, they’re not so good at showing which is the central topic, where I should start reading to grasp an overview of the whole structure.

Another limitation of both mind maps and concept maps is that they work well if you have something between ten and fifty items; but if you have a hundred or more, the metaphor starts to break.

I have seen concept maps from NASA that were so complex, you would have to follow the arrows with your finger to see where it leads in the end, because they were just too big and had too many connections to actually just grasp the structure with your eyes. So again, they’re good for what they are good at, but they’re not good if it gets a little larger.

What about traditional note-taking apps?

Again, they’re quite good at what they are. They are made for capturing single notes and jotting something down quickly. One trick that they use is that usually you’re only looking at one note at a time, so you can have thousands or millions of notes in your note-taking base, and it can hold that easily.

What’s missing with really most note-taking apps out there is the overview. You never see the big picture, how things are structured, what the clusters are, what leads to what. That’s one aspect that mind maps and concept maps do really well: giving you an overview. Most note-taking apps don’t cover that.

What about some of the newest apps that feature a visual knowledge graph?

I still think there is something essential that is missing there: The visualizations in those apps are not stable. They take the structure of your notes and they generate a nice visualization. But if you add another note, the visual layout changes. And then, you can’t find things where they were before. It means that you cannot use your spatial memory because things look different every time.

And that’s something that I really like to tap into: using our spatial sense of orientation to get some of the cognitive load in our heads away, using a spatial system so we have more brain power left to think about the actual problem at hand.

And that’s basically the iMapping method you have developed as part of your doctoral thesis, right?

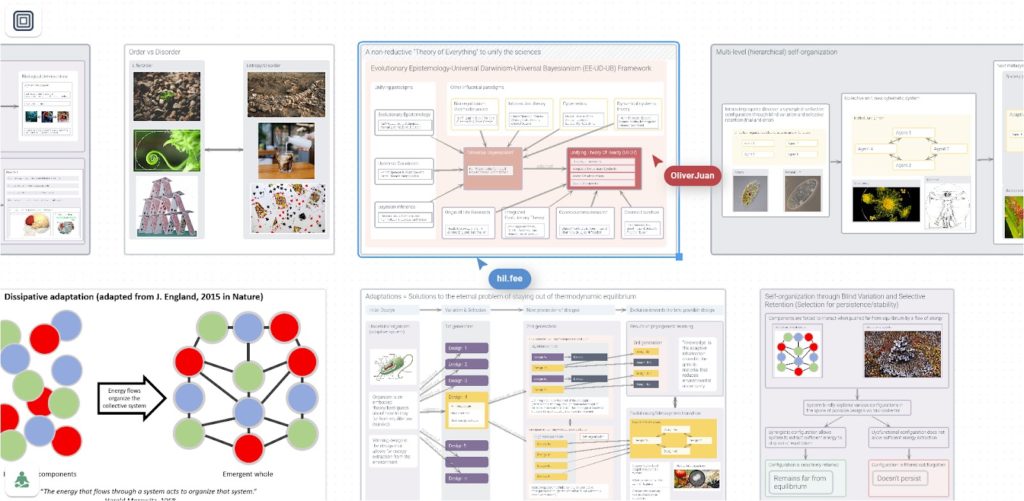

Yes, that’s what I have called iMapping. It is a way of visualizing information structures, that combines these core benefits of other approaches: hierarchy like mind maps, network structure, like concept maps, but also the simplicity of whiteboards. And as a fourth core benefit, it adds scalability in terms of holding really large amount of notes.

The trick was to make the hierarchy not like in mind maps, where it starts in the middle and then it branches from the middle out, but to turn that inside out and to make the hierarchy going from the outside in — which, as I said, is basically like the world is structured, with planets, continents, and so on. You have boxes that are nested inside other boxes, and you can use lines for the connections, but usually I don’t show them.

Many of the visualization tools we have nowadays are still based on the pen and paper metaphor. They don’t make use of all of the advantages of interactive computer systems. With mind maps and concept maps, it can become really overwhelming to see all these arrows at the same time, especially if you have large complex interconnected graphs. It’s like spaghetti.

So what we do with iMapping is that we only show connections on demand, in an interactive way, only when you touch something. And with that nesting of boxes inside boxes or cards inside cards, you can make maps as large as you want, because you never run out of space.

Another reason why we don’t make these connections front and center is because cognitive tools should make it very low effort to jot something down without thinking about the structure and the spatial mapping, without thinking about what this is connected to and where exactly it should go.

Similar to a whiteboard where you can just write or add a sticky note wherever there’s some space where — you just put it somewhere before you know what’s the right place for it — with this kind of canvas space, you can just write or throw things wherever you want and then structure it later.

So iMapping combines the advantages of mind maps, concept maps, and whiteboard, without any of the drawbacks. How did you translate this theoretical framework into Infinity Maps, which is an actual working tool?

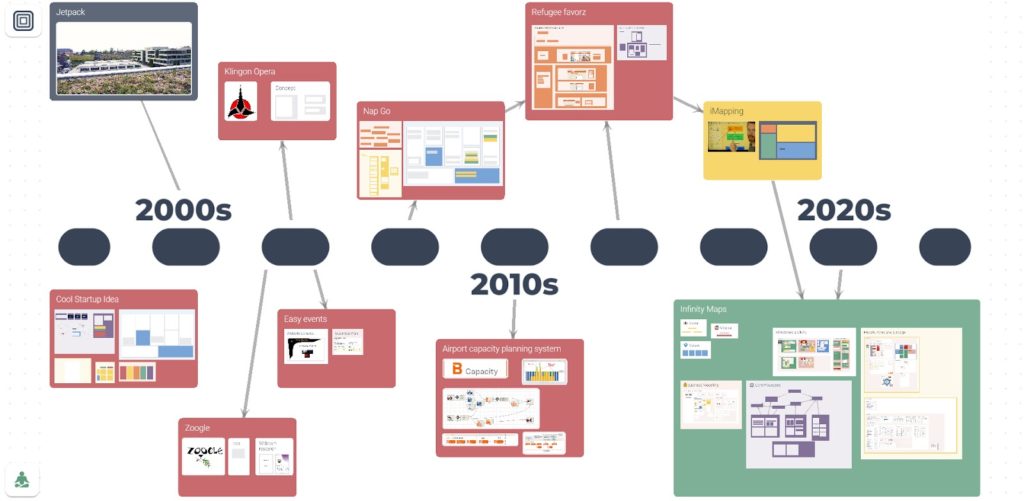

It was a long journey. My master’s thesis consisted in comparing all these visual approaches. I then decided to pursue a PhD to explore the idea of combining these approaches together. Doing a PhD seemed like a great way to have access to an environment where I would get some time and money to evolve the idea, and I could work with computer science students who would implement it.

The first prototype was simply called the iMapping tool. It was good enough to be actually used, so I started putting my notes from my dissertation in the tool and map it all out. It was such a boost in productivity. I could get all these thoughts sorted and structured, and see what is done, what is connected, what is missing, what the next steps are.

If you deal with a certain topic for say, longer than a day or a week, things tend to get so large that it’s really helpful to have everything in one overview.

After that, there was a research prototype which was free out there on the web. A magazine wrote about it and about a couple of thousand people signed up. That’s when I thought that there was some interest, and I decided to hire a couple of students to kind of get that prototype to a product level so people can actually safely use it without any fear of losing data.

It was only a couple of years ago that we really took this to the next level with my co-founder Johannes, who put together a great team. We got an investor and we rebuilt the whole thing. It now runs in the browser as Infinity Maps.

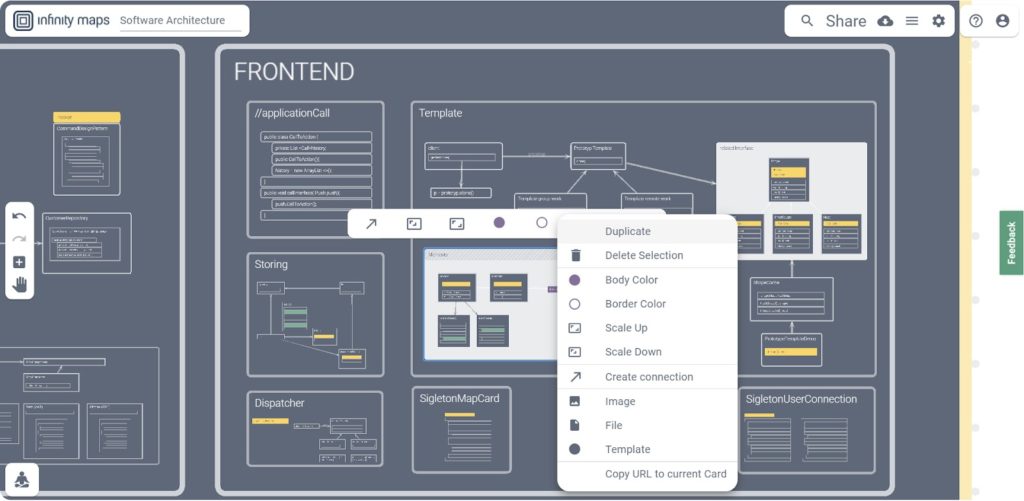

And how does Infinity Maps work exactly?

When you open Infinity Maps for the first time, you will see an empty canvas. You start with making a list of topics, of ideas, of whatever you want to map. As soon as you have more than a handful of things, you usually naturally develop the wish to add some structure. You think, this is two buckets, this goes here and that goes there. And then you have the first level of hierarchy.

As you go on taking notes, the map gets larger and larger — that’s really the way that most maps are made, they grow as you use them. And when you map out your thoughts or your ideas well, it creates additional ways to remember those pieces of information just by creating a visual impression of it. Just because you have built it, it will be easier to remember because you have put some thought into the structure, and you have a mental picture of it even without using the map.

Then if you actually use the map, you can see things that you have thought about next to each other. When you visit one, you notice the other just by passing by, which is different than if you use a search function, and where you get a list of things that have similar names and then you jump right in.

With search, you don’t see the file sitting right next to it in the same folder. You don’t see the file that has a different name, but that is actually relevant, but that you don’t remember and won’t stumble upon because you don’t see your surroundings. With Infinity Maps, you visually go there and you see everything that is related.

There’s a great paper called Finding and Reminding that elaborates on these different thinking modes and how you should always cover both. This reminding aspect of Infinity Maps is something that helps you stumble upon things when you need them, although you don’t explicitly look for them.

That makes sense. You’ve had a long journey already. What’s your vision for the future of Infinity Maps?

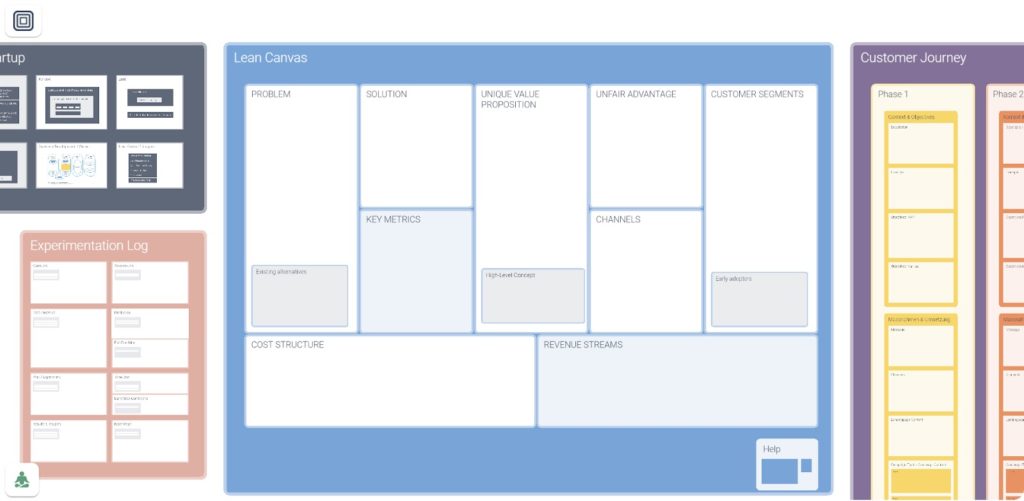

I think this will be the way many knowledge workers will work and think in the future — a cognitive tool that lets you build big maps. But there are so many possibilities to integrate existing tools and approaches. After all, it’s all boxes, and in the box, you can put videos, you can put other apps, you can put other visual content. Infinity Maps will become the wrapper around all the other things.

There are so many tools that are perfect at what they are made for, but what’s missing is something that embraces it all. So you can put things that belong with each other next to each other, although they live in different tools. We want to be the visual knowledge workbench of the future.

Thanks so much, Heiko! Where can people learn more about Infinity Maps?

You can sign up on infinitymaps.io, and follow our journey on Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, YouTube, or Twitter.