Netflix just added an 847th show you might like. And yet, you’re more likely to scroll endlessly than actually watch something. Having infinite choices is supposed to be the ultimate freedom. So why does it feel like prison?

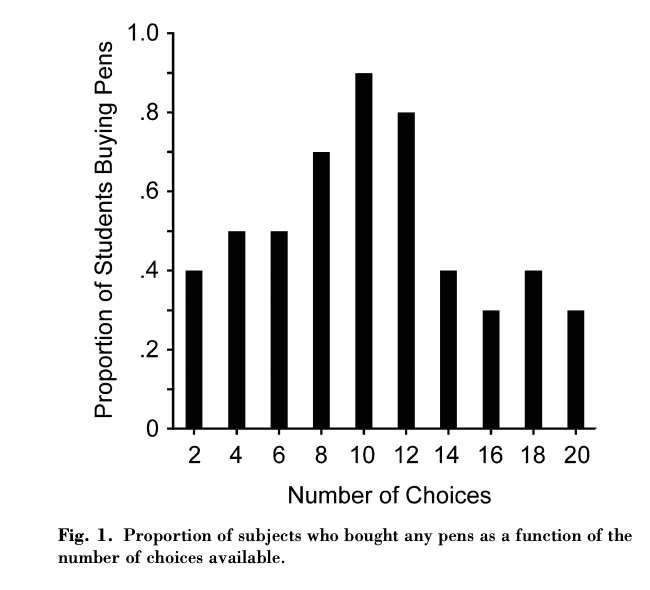

The answer lies in what psychologist Barry Schwartz calls the paradox of choice. When faced with too many possibilities, we don’t feel liberated. We freeze up, delay decisions, or avoid choosing altogether.

This isn’t just a modern Netflix problem. The term “choice overload” was coined by Alvin Toffler back in 1970, long before streaming services existed. Research has since revealed that satisfaction with our decisions follows an inverted U pattern: there’s a sweet spot between too few and too many options that maximizes both our sense of freedom and mental well-being.

With too few alternatives, we feel constrained and frustrated. But pile on too many, and we experience analysis paralysis, fear we’re missing something better, and second-guess ourselves afterward.

We think: was there really no superior option lurking among the dozens we didn’t pick?

Unfortunately, we rarely control how many choices get thrown at us. Grocery stores are said to carry 40,000 more items than they did in the 1990s. Dating apps serve up endless profiles. Even our potential career paths have multiplied.

That’s probably why most of the 35,000 decisions the average American makes daily might feel more burdensome than freeing.

But there’s encouraging news: we can learn to navigate this abundance without drowning in it. The solution isn’t eliminating options but developing better strategies for handling them.

1. Anchor yourself. Before diving into options, define what matters most. This is called expected utility. Laptop shopping becomes a bit more manageable when you’ve already decided portability is more important than performance.

2. Narrow the field. Your brain processes comparisons best with three to five contenders, not thirty. So instead of looking at the options in a vacuum, group them together so they are easier to evaluate. For example, if you’re looking at potential options for a Friday night dinner, you could frame them by types of food, or eating-out vs eating-in.

3. Create a deadline. Extended deliberation will only increase doubt. Create deadlines like ten minutes for lunch choices or two days for major purchases. This kind of artificial time pressure will help prevent the endless research rabbit holes that won’t materially improve your choice.

4. Choose good enough. Studies consistently show that people who settle for satisfactory solutions report greater happiness than perfectionists. As we say in French, “Un tiens vaut mieux que deux tu l’auras” – what’s yours now is worth more than what may come tomorrow.

What we call freedom of choice often becomes its own form of captivity, but applying these simple principles will help free up mental energy for choices that genuinely deserve deeper consideration.

In essence, true freedom isn’t having unlimited options. It’s developing the wisdom to choose confidently from whatever options exist, then moving forward without looking back. Freedom is being able to make decisions that let you actually live your life.

Tiny Experiment of the Week

Ready to put those ideas into practice? This week’s tiny experiment is designed to help you practice choosing with less second-guessing.

I will [limit one daily decision to 5 minutes] for [5 days].

Try it with simple choices like what to eat, what to wear, or what task to start first. This experiment will teach you to trust “good enough” instead of searching for perfect. Want to dig deeper? Get your copy of Tiny Experiments.

Until next week, stay curious!

Anne-Laure.