In my book Tiny Experiments, I used Amelia Earhart as an example of a life lived through experimentation and adventure. Her willingness to try new things perfectly captured the spirit I wanted to encourage in readers.

To my surprise, some people pushed back: “She’s a terrible example,” they effectively said. “She was just a publicity puppet and look at the way she died.” (we don’t know for sure but she probably crashed into the Pacific Ocean during her attempt to circumnavigate the globe in 1937)

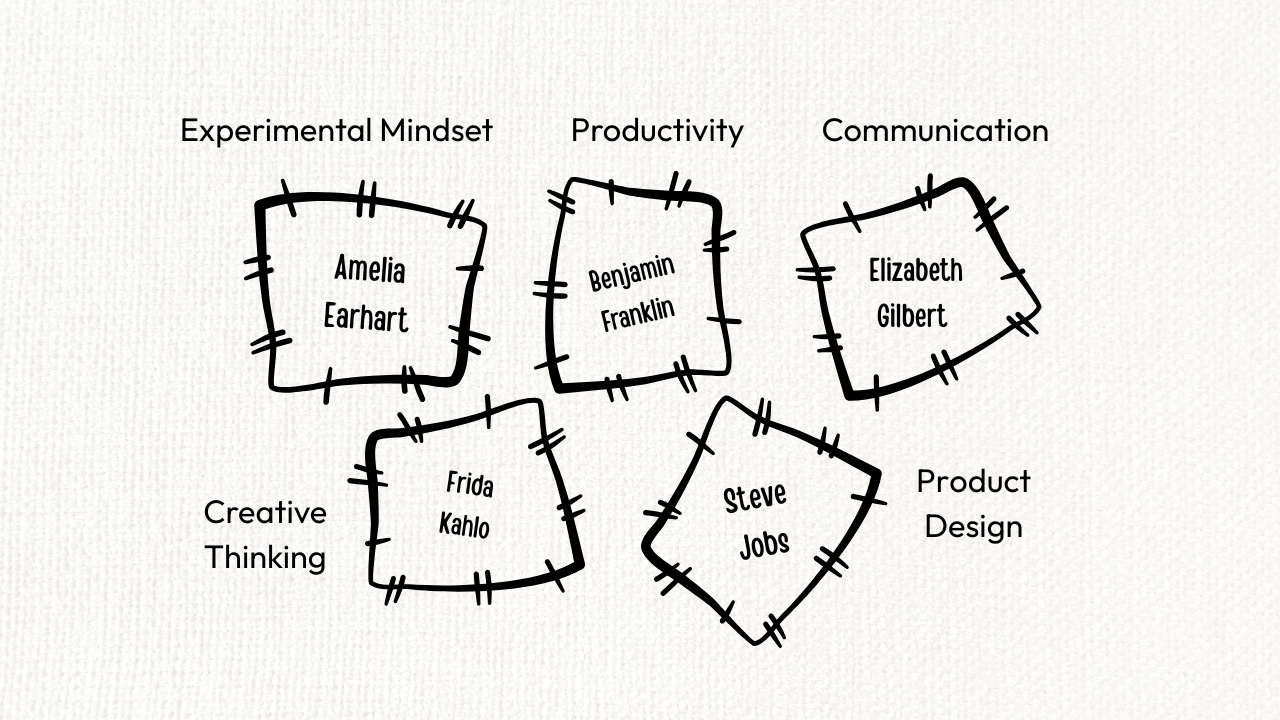

But I wasn’t asking readers to emulate everything about Earhart’s life, make the same career choices, or even share her particular relationship with risk. I was only drawing inspiration from one specific quality: her experimental mindset.

This got me thinking about how we approach role models. What if we stopped expecting them to be perfect in every area? What if we could take the best parts and ignore the rest?

The Need for Selective Admiration

The myth of the perfect hero creates an impossible standard. When someone we admire shows behavior we disapprove of, we feel disappointed and often throw out valuable lessons along with the flaws.

Philosopher Susan Wolf has written extensively about “moral exemplars” and the problems with expecting too much from role models. Take Martin Luther King Jr. His civil rights leadership remains inspiring despite personal complexities. Should we abandon his dream of equality because he wasn’t perfect in every domain?

Steve Jobs revolutionized product design but his interpersonal relationships were notoriously difficult. We can learn from his design thinking without copying his approach to people. We can admire Pablo Picasso’s creative courage while rejecting his personal behavior. Marie Curie’s scientific dedication can teach us about determination and curiosity, but we wouldn’t look to her as an exemplar for mentorship.

What’s interesting is that research shows we naturally pick and choose behaviors to model, which means we’re already building a patchwork of role models unconsciously. But when we consciously choose role models, we override this natural tendency and somehow demand perfection instead.

When we abandon the myth of the perfect hero, something liberating happens: we stop waiting for perfect moral exemplars and start learning from imperfect humans.

This is what happened with my Earhart example. Her willingness to explore and iterate perfectly embodies an experimental mindset. Her other choices, her relationship with fame, her tragic end… none of that mattered for what I needed to learn.

This is especially important in our social media age. We see curated versions of people’s lives that create unrealistic expectations. A patchwork approach to finding our role models reminds us that real people are complex, and that’s exactly why their strengths can be instructive.

How to Create Your Patchwork

Creating your own patchwork of role models doesn’t have to be complicated, but it does require some intentional thinking. Here are three strategies for curating inspiration without demanding perfection:

1. Identify a specific quality first. Don’t begin with the person and try to admire everything about them. Start with what you want to develop. Creative confidence? Leadership skills? Better boundaries? Once you’re clear on the specific quality, look for people who excel at that trait, regardless of their other areas. (also note, these people don’t have to be famous – a coworker, friend, or family member can be a great role model too!)

2. Set boundaries around your admiration. Be explicit about what you’re learning and what you’re not. You can even use specific language: “I admire Maya Angelou for her courage in writing about difficult experiences, but not necessarily her approach to relationships.” This metacognitive practice will create clarity about what supports your growth.

3. Allow for complexity and change. People evolve, and so does the moral context in which we evaluate them. Historical figures who were progressive for their time might seem problematic by today’s standards. Contemporary figures grow and change. Rather than seeing this as a problem, treat it as useful information, and periodically reevaluate your patchwork of role models.

As a bonus, if the person you admire is still alive, you might even tell them. It’s a great way to connect with others. A simple message like “I really admire X and Y about you / your work” can make someone’s day and maybe lead to a new or deeper connection.

The patchwork approach isn’t about lowering your standards, it’s about creating your own standards. Instead of passively admiring distant heroes, you become an active curator of wisdom. You see people as they are: complex beings with strengths and limitations.

This honors the full humanity of people we learn from rather than turning them into icons.

Most importantly, it makes us kinder to ourselves. If you don’t expect perfection from your role models, you’re less likely to demand it from yourself. You can pursue excellence in areas that matter while accepting you’ll always be a work in progress (see the “Intentional Imperfection” chapter in Tiny Experiments).

Your experimental mindset might be inspired by an aviator, your creative courage by a painter, your scientific rigor by a researcher. There’s no rule saying these qualities must come from one person.

The most inspiring life you can build will be uniquely yours, assembled from lessons learned and wisdom gathered from the imperfect humans who came before you.