Our culture loves experts. Whether it’s athletes, chefs, or musicians, some of the biggest celebrities are considered masters of their craft, and we admire the long hours they put into practicing over and over again the same skills so they could become second nature.

In 2008, Malcolm Gladwell published his popular book Outliers, exploring why some seemingly extraordinary people achieve much more than others. The book mentioned a study of violin students at a German music academy. This is from the abstract: “Many characteristics once believed to reflect innate talent are actually the result of intense practice extended for a minimum of 10 years.” Malcolm Gladwell branded this the 10,000-hour rule. Study whichever topic for 10,000 hours, and you will master it.

Practice doesn’t make perfect

First, the study wasn’t about studying a topic for a specific amount of time. It was about deliberate practice. This is a type of practice that is systematic and purposeful, with the specific goal of improving performance and requires focused attention rather than mindless repetitions.

More importantly, the lead researcher of the study himself doesn’t even seem to agree with the magical 10,000-hour rule.

“He misread that as every one of them had actually spent at least 10,000 hours [practicing], so somehow they passed this magical boundary (…) They were very good, promising students who were likely headed to the top of their field, but they still had a long way to go at the time of the study.”

Anders Ericsson, Psychologist & Researcher, Florida State University (source).

Finally, and maybe the biggest problem with the 10,000-hour rule, there is absolutely nothing in the study that suggests that anyone can become an expert in any given domain by putting in 10,000 hours of practice, even deliberate practice. To show this, the researchers would have had to take a random sample of people through 10,000 hours of practice and see if the results were statistically significant.

All the study shows is that the “best” violinists had put in more hours of deliberate practice than the “good” violinists. Which is interesting but by no means a promise of expertise.

In fact, a research study from Princeton shows evidence that practice accounts for just a 12% difference on average in performance in various domains, specifically:

- 18% in sports

- 21% in music

- 26% in games

As Frans Johansson explains in his book The Click Moment, deliberate and repeated practice works better in fields with stable structures, such as chess, classical music, or tennis, where the rules never change. But, when it comes to entrepreneurship and other creative fields, the rules change all the time, making deliberate practice less useful.

So if practice doesn’t make perfect, how can we go about mastering new skills?

Range over mastery

The learning strategy that has been used traditionally in school to teach students consists in focusing on one skill before moving on to the next one and is called blocking. But there is a better way: interleaving, which consists in practicing multiple parallel skills at once.

Research has shown that randomizing the information causes your brain to stay alert, helping to store information in your long-term memory. This means that the next time you want to study a new subject, you could benefit from switching things up. For example, a bit of coding mixed with a bit of UX design will work better than one long coding session.

Not only will you learn better and faster, but it may also make you more successful in the long run. In his book Range, David J. Epstein shows how generalists, rather than specialists, are more likely to succeed, especially in complex fields.

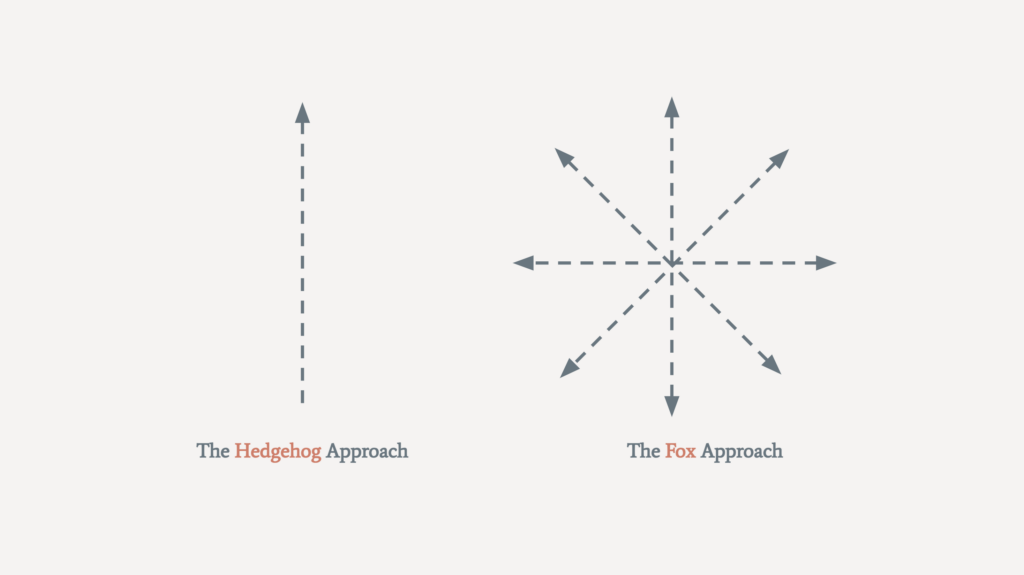

The graph below is based on the Ancient Greek proverb: “The fox knows many things; the hedgehog one great thing.”

Being too much of an expert can even be detrimental. In Expert Political Judgment, Philip E. Tetlock shares an experiment where political and economic experts were asked to make predictions. Turns out, 15% of outcomes that experts had considered impossible came to happen anyway, and a quarter of what constituted virtually guaranteed outcomes were never predicted.

The interesting part? The more experience and credentials these experts held, the further off the mark their predictions were. In contrast, the participants who had a wider range of knowledge areas and were not bound to a specific “expertise” domain fared better in their predictions.

Being able to see new patterns and generate ideas across fields where people don’t usually make connections is an incredibly valuable skill. This superpower rarely comes with deep expertise in one unique field at the expense of other areas of knowledge.

So, forget about the 10,000-hour rule. Forget about sticking to one area of expertise for many years. It may work for a very small subset of people, but there is no rule indicating that this is the best strategy. Next time you feel like studying something new that doesn’t fit neatly into your current “frame of expertise”, go ahead and just do it.