When I was a kid, I used to think I was doing much better at tests when using a particular pencil my sister had gifted me. So I would make sure to use this pen for every test.

I have a friend who thinks that city people are generally rude. So when he meets a rude stranger, he assumes they must have grown up in a city. These illusory correlations are all around us, and we use them more often than we realise.

Originally coined by Loren Chapman and Jean Chapman – yes, they share the same last name – the term “illusory correlation” describes our tendency to overestimate relationships between two variables even when no such relationship exists. Why do we do this?

Protecting ourselves from the unpredictable

Illusory correlations feel like simple rules of thumb to use in decision-making. It’s especially true in fast-paced environments where we don’t have enough mental energy to take the time to think.

For example, Dr. David Mandell of the Children’s Hospital in Pittsburgh found that 69% of surgical nurses in his study believed that a full moon led to more chaos – and hospital admissions that night.

“In any high-stress, fast-paced field like medicine, superstitions run rampant when you feel a loss of control. This is especially true of emergency environments because you never know what will walk in. You need some way to explain the unpredictability of your environment.” — Dr. David Mandell.

When stressed or tired, we use a mental shortcut and use the most easily accessible information when evaluating a specific topic or decision. We feel like if something easily comes to mind, it must be important, or at least more important than alternative pieces of information which are not as easily recalled. And so we make connections and correlations where none exist.

We fall prey to illusory correlations in many areas of our lives, often without realising it. We may even feel like we’re being smart by spotting connections where nobody else seems to have noticed!

- You fail a job interview on a Friday, so you determine this is a bad day for interviews, and you decide to avoid doing job interviews on Fridays.

- A man gets his bag stolen by a person of a specific demographic. In the future, he hugs his bag close to his body each time he crosses paths with a person of that demographic.

- A football player wins a game when wearing a certain pair of shoes for the first time. He decides to keep on wearing these socks for future games.

- A woman lives next to university students who party a lot. When she moves to a new home, she refuses to live near students, as she assumes all of them are loud.

As you can see, most of these illusory correlations can be rationalised. Fridays are bad for interviews because all interviewers are tired after a long week of work. The football player may have won the game while wearing these shoes because they are more comfortable.

And that’s the point: illusory correlations are powerful because it’s easy to rationalise them.

Spotting illusory correlations

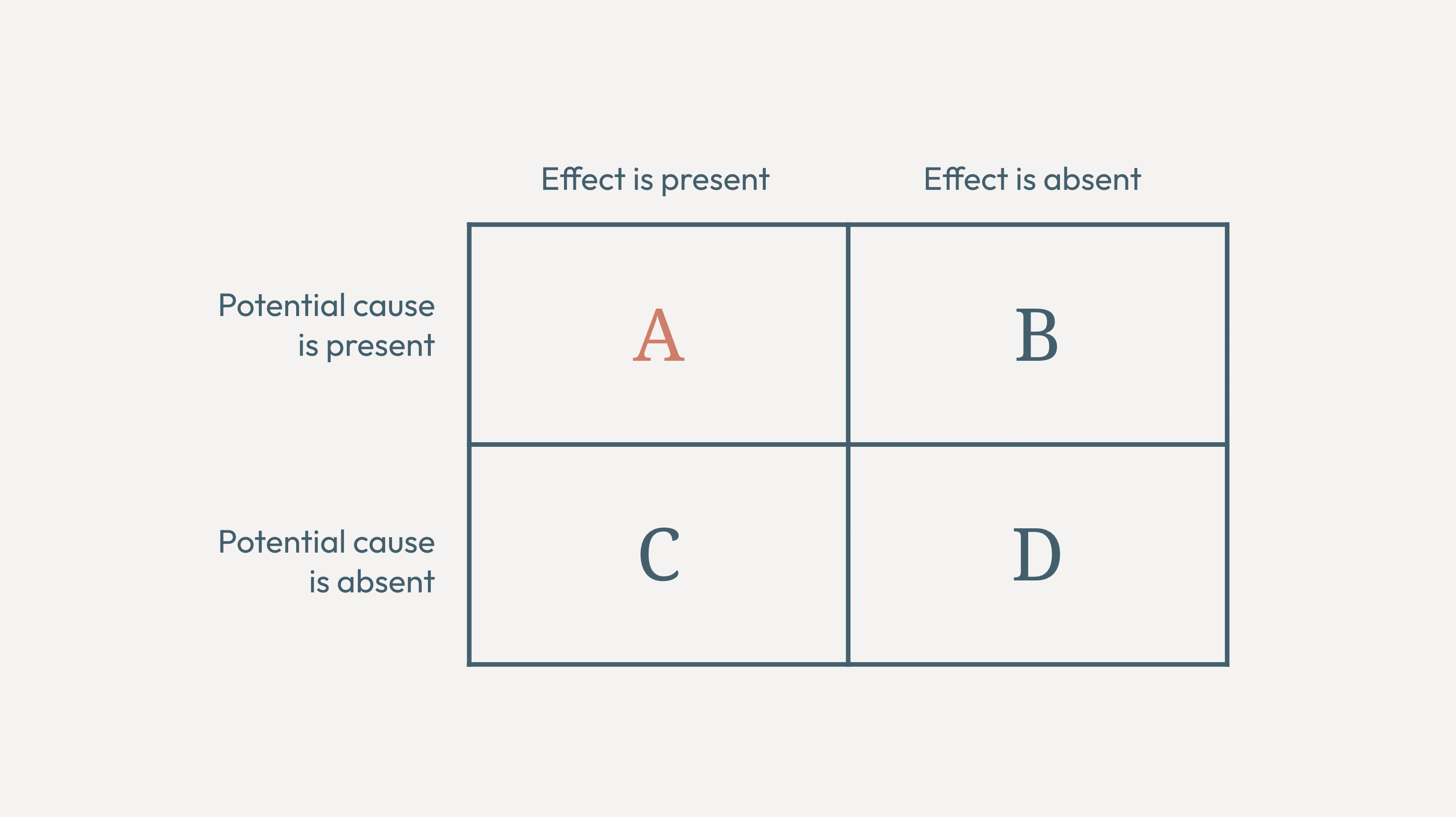

When are we most likely to fall prey to illusory correlations? A great way to spot these is to borrow from the field of statistics and use a contingency table. I borrowed the matrix below from a research paper about causal illusions, which are similar to illusory correlations but take it a step further by assuming causation.

A. The effect (winning a game, failing an interview, or having lots of hospital admissions) is present, and the potential cause (yellow socks, Friday, full moon) is present as well. As discussed earlier, the availability heuristic makes this combination striking and memorable. We are most likely in this case to create an illusory correlation. When I was wearing these socks, I won that game. When I interviewed on a Friday, I failed to get that job, etc.

B. The effect is not present (you don’t win a game or fail an interview), so you don’t spend time trying to find an explanation. This is a non-event.

C. The effect is present, but the potential cause isn’t. We tend to dismiss these as there is no immediately available information that would help us create a reassuring rule of thumb.

D. Both the effect and the potential cause are absent. We rarely stop to think when things go smoothly, so we mostly ignore these occurrences.

Only the first cell causes us to imagine a correlation where none exists. Something happens, a potential cause is present, and voilà – you got yourself the perfect recipe for an illusory correlation.

The issue is that these illusory correlations then drive many of our decisions. So, next time you hear yourself saying “when I do X, Y happens” take a few minutes to pause and think. Is there really a correlation between the event and what you imagine being the cause? Could Y be explained by another cause? Could Y have happened just because it did?

Just take a few minutes to think aloud or write it down in your note-taking app.

Challenging your assumptions is essential in order to uncover hidden patterns that drive your thinking without you being aware of the powerful mechanics inside your mind. This metacognitive practice takes some effort, especially when we’re stressed and tired, but it’s often well worth the extra mental energy if you’re basing a big decision on that assumption.