My grandma just passed away. Oma was 86 years old. She was born in Algeria, in a small village called Sidi Okba. She had tattoos on her face, which she didn’t like and tried to get rid of several times, to no avail. She also didn’t like drunk people and violence. What Oma liked, though, was chocolate—chocolate croissants, pain au chocolat, anything with chocolate—which was not great for her diabetes, but no one could resist her, and she somehow always had chocolate in her hand.

I had just finished a meeting when I learned the news. A few missed calls, and a short text saying Oma had left us. Partly because I didn’t have to come up with anything to say or to speak to anyone, my mind initially went blank. Then, my first thought was: “But we never got to record her story.”

It’s not the first time I have had this thought. Oma could only speak Algerian Arabic, a spoken dialect, and never learned how to write. I don’t speak Arabic, but Algerian Arabic uses many loanwords from French, so I could always more or less understand Oma. For example, “tilifun” is telephone (same as in English), “tunubil” is automobile (car). We had one phrase in particular we always kept telling each other since I was a little child: Pas pleurer, pas ‘nerver (“no cry, no angry”). But I didn’t have enough vocabulary to have deep conversations with her. She would speak in Arabic, and I would reply in French. Lots of our communication was through touch, smiles, hand gestures, and our tone of voice.

So, last year, when I decided to write a memoir of Oma’s experiences, I turned to my mom. During one of our visits, we sat down, and I pressed record on my phone while my mom asked Oma questions about her childhood. How did you spend your days? How did you meet your husband? My mom was translating bits and pieces to me as we went, but I told her not to worry too much as we could do the translation later.

One of my biggest regrets is to have failed to backup that recording. I’m so used to everything being automatically uploaded to the cloud that when I gave my old phone to my little brother, it didn’t occur to me that these audio files stay on the device by default. So we wiped the phone out, and that was it. Since then, I have been wanting to record her story again. But everytime we visited, she seemed too tired, and I didn’t want to bother her.

When Oma died and I got my mom on the phone, one of the first things she asked was: “Do you remember that recording?”

“Our dead are never dead to us, until we have forgotten them,” wrote George Eliot. The idea of dying twice—once when your heart stops beating, once when your name is pronounced for the very last time—has been around for as long as humans have started transmitting tales of great feats to their progeniture. It’s called legacy.

“Someday soon, perhaps in forty years, there will be no one alive who has ever known me. That’s when I will be truly dead – when I exist in no one’s memory. I thought a lot about how someone very old is the last living individual to have known some person or cluster of people. When that person dies, the whole cluster dies too, vanishes from the living memory. I wonder who that person will be for me. Whose death will make me truly dead?” ― Irvin D. Yalom.

To me, writing and sharing about Oma—posting her photo on Twitter, documenting my grieving journey—are ways to hack the system. I’m uploading Oma to everyone’s memory, so she may outlive herself.

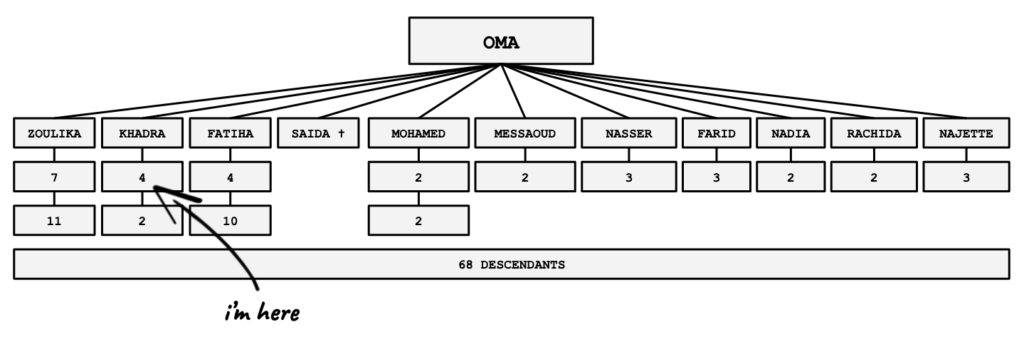

But the truth is, she may have managed to hack the system herself. Oma could not write, but she wrote another kind of code, the kind that may endure through a few generations; the kind that may resurface memories of your life many centuries later if one of your descendants is into genealogy. Oma had a big family.

I find this tree beautiful because we are more used to seeing genealogical trees facing upwards: starting with yourself and going up the branches to explore who lived in your past. But in Oma’s case, beyond her parents, there is very little information about her ancestors. This future-forward genealogical tree capturing her legacy is a better representation of where she stood in the world.

In these times of change, I think it is important to ask oneself: what will my legacy be? How do I live beyond my expiration date? What are the choices I make today that I want to be remembered for tomorrow? Our future past is a more useful construct than our future or our past.

In 1945, Dr. Vannevar Bush wrote a visionary article titled As We May Think, which anticipated many aspects of information society. In it, he laments about the loss of precious information in the scientific world.

“Mendel’s concept of the laws of genetics was lost to the world for a generation because his publication did not reach the few who were capable of grasping and extending it; and this sort of catastrophe is undoubtedly being repeated all about us, as truly significant attainments become lost in the mass of the inconsequential.”

To create a collective memory, he suggests a device where each individual could record all of their knowledge, which he calls a memex: “A memex is a device in which an individual stores all his books, records, and communications, and which is mechanized so that it may be consulted with exceeding speed and flexibility. It is an enlarged intimate supplement to his memory.”

Notice the emphasis on the written word. What would Oma’s memex look like? There are a few limitations. Remember that Oma didn’t write. Even if she did, not everyone wants to sit down and record their thoughts. And recording all of one’s thoughts may either be impossible or undesirable.

I recently read a short story by Borges in his book Labyrinths, called Funes the Memorious. Funes is a young man who, after an accident, becomes cursed with a strange ability: he can now perceive and remember everything. (“Now his perception and his memory were infaillible.”)

Funes considered creating a mental catalogue of all the images in his memory. But he did not proceed. “He was dissuaded from this by two considerations: his awareness that the task was interminable, his awareness that it was useless. He thought that by the hour of his death he would not even have finished classifying all the memories of his childhood.”

As much as I wish Oma had created a memex I could consult today, the current technological limitations mean that building such a mental catalogue would have robbed her from investing in what she considered her most important legacy: her children, grand-children, and grand-grand-children.

How could we instead capture an individual’s memories in a way that is so organic, it blends into their lives? Of course, brain-computer interfaces first come to mind. But again—do we really want to keep a record of everything? Isn’t there some good in our individual and collective memory’s natural selection process?

Maybe the perfect device would record everything, and only resurface the most meaningful moments. The ones our poor natural memory makes us wish we could remember better.

I’m not sure I want to know everything about Oma. Forgetting the trivial is part of healing. What I miss is her smiles, her kisses, the way she managed to get the nurses to bring her chocolate, how her eyes were laughing when she was eating it, and how she always repeated: “Pas pleurer, pas ‘nerver.”

“No cry, no angry.”