Our current education system is designed to optimise for input. Hours are spent reading, observing, and listening, and output is mostly encouraged as a way to measure the student’s progress. It’s a shame, because there’s lots of research showing that we remember things better when we actively engage with the information and create our own version of it. This is the principle behind the Feynman Technique, named after Richard Feynman (1918–1988), a Nobel-prize winning physicist.

Feynman was called The Great Explainer. He pioneered the entire field of quantum electrodynamics, influencing the fields of nanotechnology, quantum computing, and particle physics. He was a passionate and incredibly talented teacher, able to synthesise and explain complex scientific knowledge to his students. Bill Gates called him “the greatest teacher I never had.” Someone who did have the opportunity to interact directly with The Great Explainer is Albert Einstein, who attended a lecture Feynman gave as a graduate student.

Unlike many scientists who mostly use writing to communicate their ideas, Feynman relied heavily on verbal channels, such as talks. Most of his work was transcribed from his lectures. He even dictated most of his books. And this focus on oral communication and teaching others as a way to learn are the basis of the Feynman Technique.

“Without using the new word which you have just learned, try to rephrase what you have just learned in your own language.”

Richard Feynman, Physicist.

How to apply the Feynman Technique

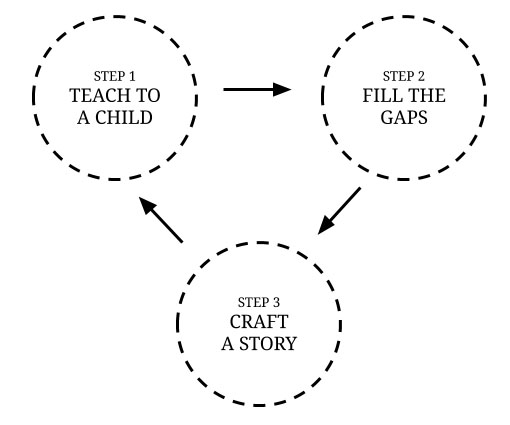

There are only three steps to the Feynman Technique, and it’s easy to apply them straight away. Once you have picked a topic that you’ve recently been studying, test your knowledge by trying to transmit it.

- Pretend to teach the concept to a child. Imagine you’re a middle-school teacher and you need to teach what you’ve just learned to a child. Take a piece of paper and write down everything you know about the subject. Remember your imaginary audience and keep your explanation jargon-free. Don’t hide behind complicated words to mask the gaps in your knowledge. How exactly would you explain this concept to a kid who has no prior knowledge of the subject? Feel free to use doodles to make it easier to grasp. Feynman was a huge fan of visual aids.

- Fill your knowledge gaps. At some point during this process, you will inevitably get stuck. Perhaps you won’t manage to come up with a simple way to explain part of the concept, or perhaps you’ll realise that an element still feels fuzzy in your mind. That’s perfectly fine: this is actually where the magic happens. Go back to the source material to make sure you understand the concept, and keep on creating your own, simple explanation.

- Craft a story. Now that you have everything you wanted to learn on your piece of paper, it’s time to turn it into a compelling narrative by organising and simplifying it. Again, think of the imaginary child this explanation is for. Use analogies and comparisons. Read it out loud to see if it flows and to make sure you’re not skipping any steps in the explanation. Once you get to this point, you can be sure you have truly mastered the topic at hand.

Here is an example of such as simple explanation that even a child could understand, written by Feynman to explain what atoms are:

“All things are made of atoms — little particles that move around in perpetual motion, attracting each other when they are a little distance apart, but repelling upon being squeezed into one another.”

Richard Feynman, Physicist.

And if you want to take it up a notch, you could even take your explanation and test it on someone you know. This could be done at scale in the form of an educational article. Learning by teaching is extremely powerful. Try to grab your closest colleague or a friend, and tell them about what you just learned. See if they seem to understand it. If you crafted a good story, they may even get excited.