Sometimes, things get lost in translation. If you’ve seen the beautiful 2003 eponymous movie, you’ll know how powerful culture shock can be. It’s one of my favourite films, which is why my colleagues—when I was an intern at Google—gifted me a voucher to spend an evening at the Park Hyatt Tokyo’s cocktail bar, admire the view, and walk in the shoes of Bill Murray and Scarlett Johanson. I remember sipping a drink and thinking about how hard and beautiful it was to try to communicate with someone from a different culture. Untranslatable words capture the essence of that challenge in a way that reveals the conflict arising from necessary approximations when a word simply has no direct translation in your native language.

I recently stumbled upon a research paper by Dr. Tim Lomas from the School of Psychology at the University of East London, which explores how we can enrich our emotional landscape through untranslatable words related to well-being. It’s a fascinating essay, covering more than 200 such terms.

Expanding our view of well-being

Researchers have—maybe rightly so—accused the field of positive psychology to be too focused on the Western world and its particular culture. Most studies in positive psychology have been conducted in the Western world, which would explain the inherent bias in the current state of research. While efforts have been made to address these critics, the differences in vocabulary make it difficult to simply transpose mental well-being concepts from a culture to another. This is why studying untranslatable words is so important.

In his paper, Dr. Tim Lomas describes “untranslatability” as the notion that such words identify phenomena that have only been recognised by specific cultures, the most famous example being perhaps Schadenfreude, a German word describing pleasure at the misfortunes of others. While the meaning can be conveyed through a sentence, only that culture deemed the concept important enough to create a dedicated word.

By limiting yourself to the vocabulary of your native language(s), you close yourself from concepts that may perfectly capture a state of mind, a mental health challenge, or an emotion. Naming concepts is the first step in being able to identify them, discuss them, and understand them. From a human perspective, things without a name don’t exist.

For instance, let’s look at fernweh, another German word, meaning “feeling homesick for a place you’ve never been to” or mono no aware, a Japanese word, which describes the awareness of impermanence; the gentle—almost bittersweet—sadness about the reality of life. What can these words teach us about what it means to be human?

Exploring new worlds through new words

Some concepts are so universal you would expect everyone to be pretty much aligned when it comes to naming them. But it turns out, many cultures have a different perception of some essential life concepts just because of the vocabulary they use. Let’s have a look at three fairly important ones: time, happiness, and colour.

- Time. Being brought up in a Western culture, we tend to divide time between past, present, and future. This seems as natural to us as the Sun rising from the East and setting in the West. For example, the English verb “walk” can be changed to “walked” for past actions and “walking” for current actions. But many cultures have a different perception of time, and this can be seen in the vocabulary they use to describe it. For instance, Mandarin Chinese does not have any verb conjugations. The the verb 走 (zǒu), “to walk”, can be used for the past, present, and future. Instead, Mandarin Chinese uses a collection of untranslatable words—particles—which mean “an action that occured in the past and has been completed” or “an action that has started and is continuing in the present moment.” Some other languages have many more tenses beyond past, present, and future. The Yimas language, for instance, has three different present tenses that distinguish different levels of completion. You may think the perception of time due to language differences is not that important, but it matters a lot. For example, research has found that cultures with languages that do not strongly connect present and future in their vocabulary tend to be more reckless with money.

- Happiness. Many cultures do not have a word for hedonism, which claims that happiness is the most important thing in life, and that people should pursue as much happiness and as little pain as possible. In Hinduism, happiness is not the main goal to pursue as human beings. Instead, we should be acting in accord with dharma, the all-encompassing principle that governs the universe, society, and individual lives (which is why you would want to avoid disturbing plants and animals as much as possible). Another untranslatable word related to happiness is the Japanese term ikigai, which can be roughly translated to “reason for being.” It’s such a complex term that non-Japanese people often use a Venn diagram to attempt to capture its essence. With different words for what “happiness” is really about, cultures have different goals and attach meaning to different aspects of their lives.

- Colour. How do you describe the colour red to someone who has never seen it? How do you capture its essence with words? What if you could not use the word red at all? This may be what some people learning English as a second language may feel. For example, there is no single word for the English “blue” in Russian. Instead, siniy is used to describe what English knows as dark blue, while goluboy is used for lighter blues. The interesting part? Studies found that Russian speakers were better at distinguishing between these two shades than English speakers, who only had one word for both of them. Russian people literally see these shades as two different colours, while for English people, it’s just “blue”.

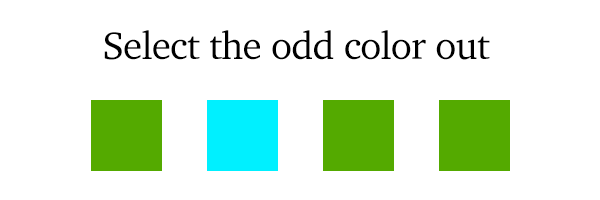

Let’s play a little game so you understand what I’m talking about. Look at the image below, and select which square has a colour that’s different from the other three squares.

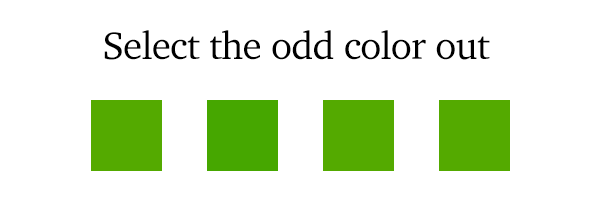

Except if you suffer from colour blindness, this should be fairly easy. Most people would be able to identify the second square—the blue one—as different from the green ones. Now, look at the following image and do the same. Which square is a different colour?

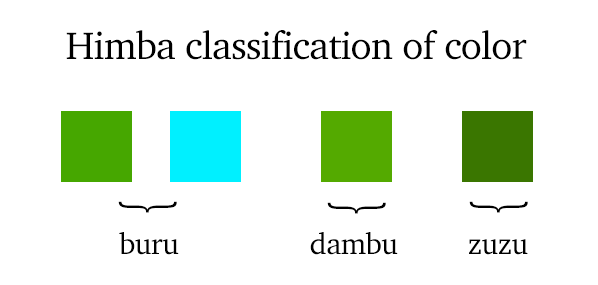

Not so easy? Turns out, people from the Himba tribe in Namibia would struggle to find the odd square in the first image, but would find it pretty easily in the second once. It’s because they only have one word for “blue” and that particular shade of green—to them, they’re the same colour—but they have several words for different shades of green. In this case, two shades of green that look exactly the same to most of us.

In fact, scientists generally agree that humans began to see blue as a colour when they started making blue pigments. And many ancient cultures had no name for it. For example, in the Odyssey, Homer makes hundreds of references to white and black, but never mentions the colour blue. He instead uses descriptions like “wine-dark” to describe blue elements such as the sea.

Related to colour, I find it fascinating how we lack vocabulary in English to describe sounds. As Dr Stéphane Pigeon explains: “Light frequencies—the colours—are some of the very first things that your baby will learn. One of the first baby books they will receive as a present, will be the one with those colourful figurines, with the name of the colour printed in bold letters: blue, red, green. As they grow up, they will learn a myriad of colour names, and will be able to distinguish them very precisely: this is not blue exactly, but turquoise, or cyan, or indigo… Later, when they look at a colour again, they will find the words to describe it precisely, and will be able to picture it in words to a friend.”

“Not with sound. The vocabulary doesn’t exist yet. Something that has no words associated with has no chance of existing culturally. Sound ‘colours’ are not in our vocabulary, and therefore, are not in our mind. (…) Such a vocabulary remains to be invented, and taught to our children.”

Why untranslatable words matter to your well-being

As Dr Stéphane Pigeon said above: “Something that has no words associated with has no chance of existing culturally.” And it is also true of our minds, our psyche, our emotions.

- Better identify your emotions. Human emotions are complex. Sometimes, the hardest part is to not being able to understand exactly how we feel. Is it just sadness, or something more complex, such as saudade, a Portuguese word describing the melancholic longing for a person, place or thing that may not even exist? Are we just stressed, or experiencing torschlusspanik, a German term for the fear that time is running out on achieving one’s life goals?

- Better communicate your thoughts. What can’t be named can’t be expressed. When trying to communicate your thoughts, untranslatable words—accompanied with their definition in your own language—can be useful tools to add to your communication toolkit. Whether in a presentation or in an email, one word in another language may express what you would usually need a few paragraphs to explain.

- Experience the beauty of other cultures. Research suggests that open-mindedness has a positive impact on cognition, decision-making, and general well-being. And what better way to become more open minded than study the strange vocabulary of foreign cultures? To really try to understand what they mean by them? You can see untranslatable words as windows into the thoughts and emotions of people from different cultures.

With all that in mind, here is a short list of untranslatable words you can use to better identify your emotions, better communicate your thoughts, and better experience the beauty in other cultures.

10 untranslatable words to increase your well-being

This list focuses specifically on words that are linked to thoughts and emotions that you may experience in your lifetime, and that may impact your mental well-being.

- Ubuntu, literally translated as “humanity towards others”, a Zulu word for being kind to others because of the universal bond that connects all humanity.

- Han (한), a Korean term expressing sadness and regret, yet also a quiet sense of patiently hoping for the adversity causing the sorrow to eventually be righted.

- Arbejdsglæde, which translates in Danish to “happiness at work” or “workplace happiness”—it’s the feeling of happiness you get from doing a meaningful, satisfying job.

- Saudade, a Portuguese word describing the melancholic longing for a person, place or thing that may not even exist.

- Torschlusspanik, a German term for the fear that time is running out on achieving one’s life goals, which I’ve described before as time anxiety.

- Aware (哀れ), a japanese word for the bittersweetness of a brief and fading moment of transcendent beauty. The term mono no aware (物の哀れ), literally “the pathos of things”, can also be translated as “a sensitivity to ephemera.”

- Ilunga, term from the Luba-Kasa language, which describes a person who’s ready to forgive abuse for the first time, to tolerate it a second time, but never a third time.

- So-won (소원), in Korean, is the reluctance to let go of an illusion.

- Ikigai (生き甲斐), a “reason for being” in Japanese, the source of value in one’s life or the things that make one’s life worthwhile.

- Wei Wu Wei (爲無爲) literally translates in Chinese to “action without action”, the deliberate decision to do nothing for a reason.

Untranslatable words are extremely powerful to better understand yourself and others. If you want to explore more untranslatable words, my friend Steph Smith created a whole website dedicated to words that don’t translate. She also wrote an amazing essay about the topic.