People think, learn, behave, and experience the world around them in many different ways. Some of this diversity is due to neurological differences. Neurodiversity refers to those variations in neurocognitive functioning. Let’s have a look at the origin of the term, and its usefulness in research and practice.

A short primer on neurodiversity

The term “neurodiversity” is relatively new: it was coined by social scientist Judy Singer in the late 1990’s in relation to autism, but has since come to encompass many other neurodevelopmental conditions such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, dyscalculia, and more.

People of standard neurodevelopmental and cognitive functioning are referred to as “neurotypical”, while “neurodivergent” is used to refer to people whose brain functions differ from what is considered standard — sometimes collectively referred to as neurominorities.

Central to neurodiversity is the idea that naturally occurring variations in the human brain should be seen as differences rather than deficits. Some people consider neurodiversity to be related to the concept of biodiversity — a term you will mostly see being used for the purpose of advocating for the conservation of species.

In the words of Dr Robert Chapman: “Proponents of the neurodiversity movement […] challenge the pathologization of minority cognitive styles and argue that we should reframe neurocognitive diversity as a normal and healthy manifestation of biodiversity.”

There is currently no definitive list of neurodevelopmental conditions that should be included under the umbrella term of neurodiversity, and some researchers even advocate for an entirely different definition that doesn’t rely on contrasting neurocognitive differences between individuals.

As Dr Nancy Doyle explains: “A definition has emerged for psychologists and educators which positions neurodiversity within-individuals as opposed to between-individuals.”

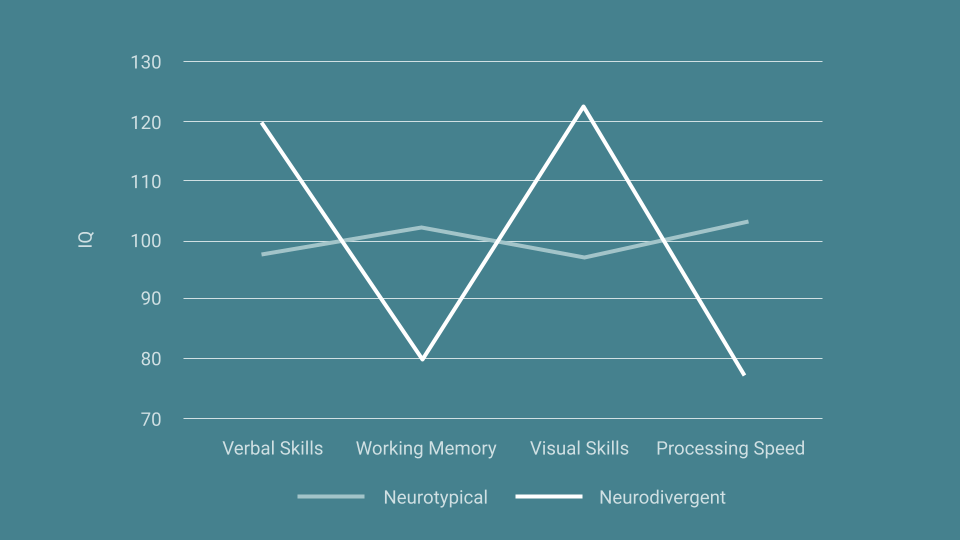

She adds: “The psychological definition refers to the diversity within an individual’s cognitive ability, wherein there are large, statistically-significant disparities between peaks and troughs of the profile, known as a ‘spiky’ profile. A neurotypical is thus someone whose cognitive scores fall within one or two standard deviations of each other, forming a relatively ‘flat’ profile, be those scores average, above or below.”

It’s important to keep in mind that neurodiversity has no official definition, and the idea does not align with the usually discrete approach to diagnosis used in medical practice — the latest Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders includes more than 150 discrete diagnoses. However, it doesn’t need to be excessively controversial.

Two complementary research models

Because the concept of neurodiversity has initially emerged as part of the social sciences, there is currently no consensus within the scientific community as to how to use it in clinical contexts.

That’s partly because the clinical model and the social model consider disability from two different perspectives. While the clinical model seeks to cure or manage disabilities, the concept of neurodiversity is based on the social model of disability, which identifies systemic barriers to the social integration of people with functional differences.

The two models have their respective critics, but they are not incompatible. In different ways, both clinical research and neurodiversity research seek to contribute scientific evidence to reduce impairments experienced by neurodivergent people: clinical research focuses on treatment, and neurodiversity research focuses on adapting environments to the diverse needs of individuals.

In a comment published in the The Lancet Psychiatry, Dr Edmund Sonuga-Barke and Dr Anita Thapar write: “Rather than a complete reliance on disorder-based concepts and related treatment approaches, we can see many advantages of incorporating the concept of neurodiversity alongside mainstream research and clinical practice.”

“Indeed, there is no contradiction between traditional approaches that look to give neurodiverse individuals additional resources through clinical treatment and neurodiverse approaches that look to adapt environments and transform neurotypical attitudes: both approaches are beneficial and together will improve the lives of neurodiverse people.”

In addition, there is growing support for a “transdiagnostic” approach that cuts across traditional diagnostic categories. Researchers from the University of Cambridge explain: “Removing the distinctions between proposed psychiatric taxa at the level of classification opens up new ways of classifying mental health problems, suggests alternative conceptualizations of the processes implicated in mental health, and provides a platform for novel ways of thinking about onset, maintenance, and clinical treatment and recovery from experiences of disabling mental distress.”

Instead of — often artificially — imposing categories onto a multidimensional and complex space, a transdiagnostic approach allows clinicians to account for the massive heterogeneity within diagnoses and for the common co-occurrence of many conditions in a way that makes a rigid taxonomy too limiting to properly support people. The idea is to consider continuous dimensions within the population, as opposed to distinct categorical entities.

Supporting neurodiversity

The concept of neurodiversity is particularly useful in environments such as schools and the workplace, where changes can be implemented to foster inclusivity and bolster people’s individual strengths while providing support for their different needs.

For instance, adjustments can be made to accommodate diverse physical needs, such as letting people fidget, having a dedicated space for quiet breaks, or offering noise-cancelling headphones.

A lot of these adjustments may even be helpful for all employees. Clear communication and documentation, flexible hours, and a school or workplace culture that emphasises kindness — all of these are good practices to implement, regardless of initiatives specifically targeted at supporting neurodiversity.

Neurodiversity is still an emerging paradigm which has been described as a “moving target”, but it already offers several practical implications for leaders who want to build more inclusive environments and researchers who want to support people across the multitude of conditions that may escape categorical labels. Hopefully this short primer will make you want to learn more!