Most scientists agree: it’s impossible to prove the truth. However, by using inductive and deductive reasoning, we can get closer. While both are based on evidence, they provide two different ways of solving problems, making decisions, and evaluating facts. But before we take a closer look at the difference between inductive versus deductive reasoning, what exactly is reasoning?

The nature of reasoning

Reasoning is considered by many a distinctive human ability, closely associated with human activities such as philosophy, science, language, and mathematics. It involves using our intellect to form logically valid arguments, and it’s one of the many ways the human mind moves from one idea to a related idea. By reasoning in a logical manner, any human being should theoretically be able to form rational connections between ideas. In the words of Galileo: “In questions of science, the authority of a thousand is not worth the humble reasoning of a single individual.”

Today, we know very little about the neural correlates of reasoning. Most of our neuroscientific knowledge concerns short-term reasoning, where scientists look at “chunks” of reasoning, such as solving a problem in a limited amount of time, or deciding which way to go when navigating a maze. The key challenge is that there doesn’t seem to be a specific “reasoning area” in the brain; instead, many parts are activated, in different ways for different people and different problems.

Our limited understanding is not for lack of practicing and thinking about reasoning. As a way of forming conclusions, inferences, or judgments from facts or premises, reasoning has a long history. The very first philosophers were fascinated with truth: is true knowledge achievable? Does absolute truth exist? Is truth objective? For thousands of years, logic and reasoning have been the preferred methods to debate these questions and evaluate the validity of the arguments.

Plato thought there was a sensible world—our physical realm—which is only a shadow of the intelligible world. In Plato’s philosophy, the intelligible world is the source of true knowledge, which can be attained through reasoning: “In the knowledgeable realm, the form of the good is the last thing to be seen, and it is reached only with difficulty. Once one has seen it, however, one must conclude that it is the cause of all that is correct and beautiful in anything, that it produces both light and its source in the visible realm, and that in the intelligible realm it controls and provides truth and understanding, so that anyone who is to act sensibly in private or public must see it.”

In the last century, Karl Popper contributed to the study of reasoning with his Falsification Principle, which states that knowledge is provisional and that we cannot definitely prove the validity of hypothesis. According to Popper, we can only disprove certain predictions by testing them. If the predictions are not correct, the theory should be rejected. Because hypotheses are constantly being improved or disproved, our knowledge is always changing. Reasoning helps us progressively get closer to the truth, but we can never be absolutely certain we have the final, complete explanation. That being said, there are several ways this process of approaching the truth can be managed:

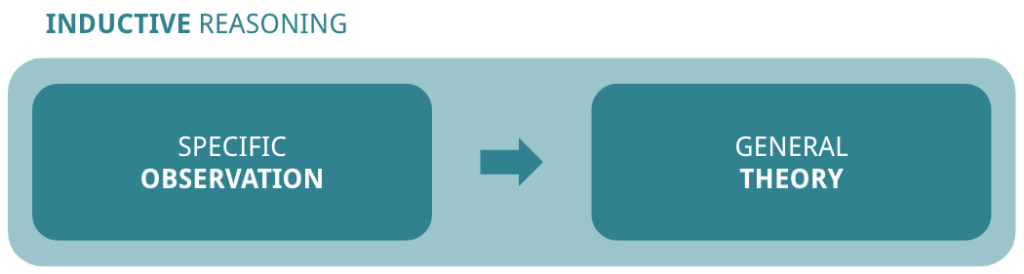

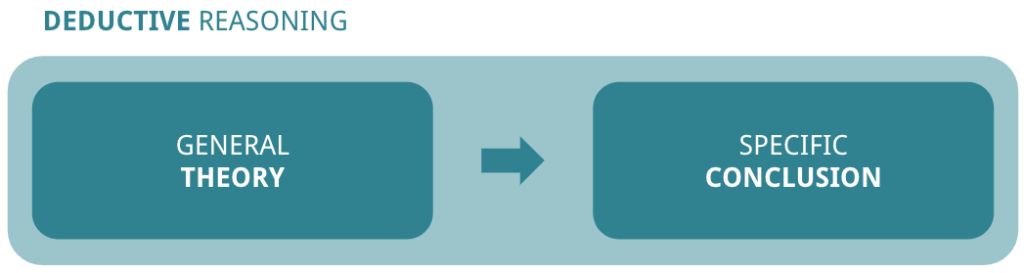

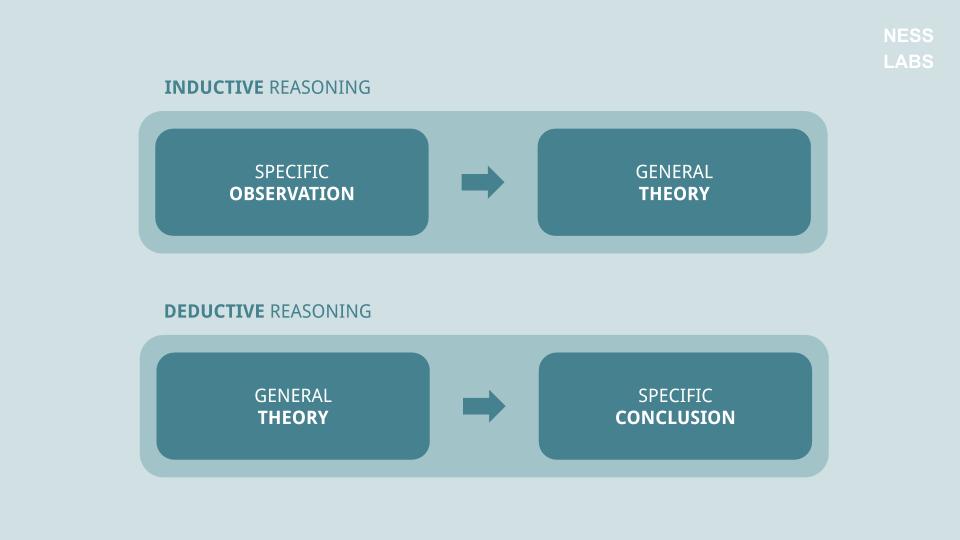

- Inductive reasoning: using your experiences and observations to come up with a general truth. The conclusions of inductive reasoning are considered probable.

- Deductive reasoning: applying logical rules to your premises until only the truthful conclusion remains. If all premises are true and the rules of deductive logic are followed, the conclusions of deductive reasoning are considered certain.

In short, inductive reasoning goes from observation to theory, while deductive reasoning goes from theory to confirmation. In inductive reasoning, we look for patterns to formulate a hypothesis, whereas in deductive reasoning, we formulate the hypothesis and see if it’s confirmed by observation. Let’s have a look at them in more detail.

Inductive reasoning: bottom-up logic

Inductive reasoning consists in looking for a trend or a pattern, and then extrapolating the information to formulate a general truth. It makes use of generalisation, causal inference, and analogies. The most famous proponent of inductive reasoning is probably Sherlock Holmes. From footprints to handwriting and oddities in murder scenes, the private detective starts from his observations to draw his conclusions. “Elementary, my dear Watson!”

Here are some examples of inductive reasoning:

- “Every time I eat peanuts, my throat swells up and I have difficulty breathing. Therefore I’m probably allergic to peanuts.”

- “The population of a city has grown by 10% every year over the past five years. Therefore, it is likely it will grow by 10% as well next year

- “Most graduates from Magdalen High School go on to university. Laura is a graduate of Magdalen High School. Therefore, Laura will likely go on to university.”

While in Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the hero is always right in the end, it’s important to note that inductive reasoning leads to intrinsically uncertain conclusions. A good illustration is the watchmaker argument, an example of inductive reasoning that claims to prove the existence of God:

“Suppose I had found a watch upon the ground, and it should be inquired how the watch happened to be in that place (…) There must have existed, at some time, and at some place or other, an artificer or artificers, who formed the watch for the purpose which we find it actually to answer; who comprehended its construction, and designed its use. Every indication of contrivance, every manifestation of design, which existed in the watch, exists in the works of nature; with the difference, on the side of nature, of being greater or more, and that in a degree which exceeds all computation.”

William Paley, the clergyman who wrote these words in his book Natural Theology in 1802, first observed the shared complexity between a watch and the natural world. He also observed that watches are designed by an intelligent maker. Finally, he used inductive reasoning to infer the existence of God from these observations. As with all conclusions reached with inductive reasoning, there is no way to prove their veracity except through direct observation.

Inductive reasoning can also lead to conclusions that are clearly wrong. This often happens when we mistake correlation with causation, or when we apply the particular to the general. For instance, you may have only seen white swans in your life. Inductive reasoning based on your observations will lead you to the conclusion that black swans don’t exist.

It doesn’t mean we should never use inductive reasoning. Sometimes, it’s the best tool we have to come up with a conclusion. We just need to be aware of the limitations of our argument, make sure we know it’s only probable and not absolutely certain, and be ready to update our judgement when new observations contradict our theory.

Deductive reasoning: top-down logic

In contrast to inductive reasoning, deductive reasoning starts from established facts, and applies logical steps to reach the conclusion. Based on facts, rules, properties and definitions, it is commonly used in science, and in particular in mathematics. Karl Popper notably said: “There can be no ultimate statements in science: there can be no statements in science which can not be tested, and therefore none which cannot in principle be refuted, by falsifying some of the conclusions which can be deduced from them.”

The most famous example of deductive reasoning is: “All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal.” You will note the nature of the premises: “All men are mortal” and “Socrates is a man” are not based on a certain number of observations you have made. Instead, they are currently the closest we have to the truth.

Here are some more examples of deductive reasoning:

- “Bachelors are unmarried men. Jack is unmarried. Therefore, Jack is a bachelor.”

- “Since all squares are rectangles, and all rectangles have four sides, all squares have four sides.”

- “If the team scores again, they will win the tournament.” The team scores again. “Therefore, they will win the tournament.”

When deductive reasoning leads to wrong conclusions, it is because either the premises or the logic applied to go from one step or another are flawed. For example: “All dogs are animals; all animals have four legs; therefore, all dogs have four legs” is wrong because, whether because of their species characteristics or because of injury, not all animals have four legs. Deductive reasoning based on false premises is extremely common, whether we do it intentionally or not.

However, deductive reasoning does lead to certain conclusions when applied correctly. It’s main limitation is that it can be impractical to use on a daily basis, as it requires us to start from factual premises, which we rarely have access to. In addition—and it is part of the scientific research process—one must be ready to update their hypothesis if one of the premises that was thought to be correct, turns out to be wrong.

Note: Inductive reasoning (a thinking process) is different from mathematical induction (a mathematical proof technique). As Peter Suber puts it: “Mathematical induction is unfortunately named, for it is unambiguously a form of deduction.” Confusing? Very much so.

Induction or deduction, that is the question

It may appear that one mode of reasoning is better than the other—but that’s not the case. Inductive reasoning and deductive reasoning should be used in combination, depending on the nature of the task at hand. For instance, researchers use inductive reasoning to formulate hypotheses and theories. Then, they use deductive reasoning to evaluate these theories in specific situations.

Even Sherlock Holmes would not use inductive reasoning to solve an equation. And deductive reasoning is not useful if you don’t have a premise to start with. Both modes of reasoning are powerful thinking tools. As such, they should be used with caution. Practicing metacognitive strategies is a great way to ensure your conclusions are valid and sound.