Chocolate or vanilla? Trello or Jira? Atom or VS Code? Stay in or go out? Should I click on this link or not? We make thousands of choices everyday, often automatically, using mental models we have created over years of experience.

Decision-making is the process we use to identify and choose alternatives, producing a final choice, which may or may not result in an action. It can be more or less rational based on the decision maker’s values, beliefs, and (perceived) knowledge.

Because we have to make decisions everyday — at work and in our personal lives — it’s surprising that smart decision-making is not taught in school. It’s the kind of skill everyone should have in their mental toolkit.

How your brain makes decisions

Neuroscientists recorded the brain activity of participants while they were either told what to do or if they could freely decide how to act.

It turns out, our brain reacts in a different way when we can make our own decisions. The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), orbitofrontal cortex and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex are all involved in this complex process.

What’s interesting is that these areas are not only involved in the formation of a decision, but also signal the degree of confidence associated with the decision.

The ACC in particular is involved in the management of what is called reinforcement information. This is when you do something, observe a consequence, and adapt your future behavior accordingly. Another study found that damage to the ACC made it difficult to use reinforcement information to guide decision-making.

So, to make decisions, you need to be able to leverage information to adjust your actions. But there’s another important source of data your brain uses in decision-making: your emotions.

Sure, we would love to think that all of our decisions are rational, but research suggests otherwise. For example, studies found that “fearful people made pessimistic judgments of future events whereas angry people made optimistic judgements.” In another study, participants who had been induced to feel sad were more likely to set a lower price for an item they were asked to sell.

According to the somatic marker hypothesis, our emotions strongly influence our decision-making. Whenever we are about to make our decision, “somatic markers” — which are feelings in our body that are associated with emotions, such as nausea and disgust, or rapid heartbeat and anxiety — act as guides telling us how to act.

One of the most visible examples of the somatic marker hypothesis is the fight-or-flight response, where a specific situation causes your heartbeat to accelerate so you can make the “right” decision to ensure your survival.

So much for rational decision-making! Making decisions actually involves hen managing a host of biological responses happening in the background as well as mental processes that are influenced by past experiences and cognitive biases.

Our mental baggage

Smart people can be — and often are — irrational. For example, half of the U.S. Congress are climate change deniers even though 97% of the scientific community strongly believes that climate change is real and that it’s a threat to the environment.

Are these Congress members stupid? That’s not the issue, according to a study published in Nature. People with “the highest degrees of science literacy and technical reasoning capacity [are] not the most concerned about climate change.”

In fact, poor decision-making rarely has to do with a lack of intelligence or information. Instead, we it’s often due to the ‘mental baggage’ we bring to the table when considering our options.

- Analysis paralysis. You may know this one under the term “overthinking.” You basically tend to spend so much time analysing all the possible outcomes that you never end up making a decision — which, often, is a bad decision in itself. Analysis paralysis is mostly driven by the fear of making a mistake, which many smart people experience, especially in high-pressure situations.

- Overconfidence. On the other hand, you may overestimate your ability to make a good decision. Studies suggest that there is no correlation between intelligence and critical thinking, the collection of mental skills that allow you think think rationally in a goal-oriented way. A little bit of self-doubt is good for decision-making. Because critical thinkers tend to be skeptical of everything, including their own ability to make decisions, they end up making slower yet better decisions than otherwise intelligent people with limited critical thinking skills.

- Information overload. We usually use information at our disposal to reduce uncertainty and make what we think our sound decisions. But sometimes, there’s more information that we can actually process. This can result in the illusion of knowledge and poor decision-making.

- Lack of emotional or physical resources. Sometimes, people are just too tired or stressed to think clearly. This drives them to make decisions based on instinct or to go for the path of (seemingly) least resistance. This is common in demanding jobs.

- The “what the hell” effect. This effect has been mostly studied in the context of dieting, but applies in many areas of decision-making. You make one small bad decision, and just think “what the hell, I may as well keep going.” You eat one donut and forget about your diet. You text your ex once and think that you may as well text them twice. You smoke that one cigarette and then go buy a pack. One small bad decision ends up snowballing into a much bigger impact.

Decision-making is a complex process, and there are many other factors such as your environment, time-pressure, and your actual and perceived knowledge that can impact the decisions you make. Being aware that you’re usually not making decisions in a vacuum is important in order to start making smarter decisions.

The three decision-making styles

While external factors are hard to predict and control, understanding your own decision-making styles is a first good step to try and make better decisions. It’s important to note that nobody has a fixed set of cognitive styles. These shift based on the current situation, the decision to make, and many of the factors we described before.

- Intuitive vs. rational. Your decision-making is the result of a fight between two kinds of cognitive processes. The first, called System 1, is an automatic intuitive system. The second (you guessed it, System 2), is an effortful rational system. System 1 is fast, implicit, and bottom-up, while system 2 is slow, explicit, and top-down. You can read more about it in the excellent book Thinking, Fast and Slow by psychologist Daniel Kahneman.

- Maximising vs. satisficing. People tend to fall under two main cognitive styles. Maximisers try to make an optimal decision, whereas satisficers simply try to find a solution that is good enough. As a result, maximisers usually take longer to make a decision, thinking carefully about the potential outcomes and corresponding tradeoffs. They will also tend to regret their decisions more often.

- Combinatorial vs. positional. The combinatorial style is characterised by a very narrow and clearly defined material goal. We tend to use this style when the objective is clearly defined. The decision-making process is more about how we will achieve the goal rather than deciding on which goal to achieve. In contrast, we use the positional style when the goal is not as clearly defined. We make decisions to absorb potential risks, protect ourselves, and create an environment where it’s less likely to experience the negative effects of unexpected outcomes.

Because being aware of your decision-making styles doesn’t mean it’s easy to shape them, it can help to use rules and frameworks to make smarter decisions. There are many frameworks for decision-making, but my favourite—maybe because of the simple acronym, but also because it’s grounded in common sense—is the DECIDE framework of decision-making.

How to make smart decisions

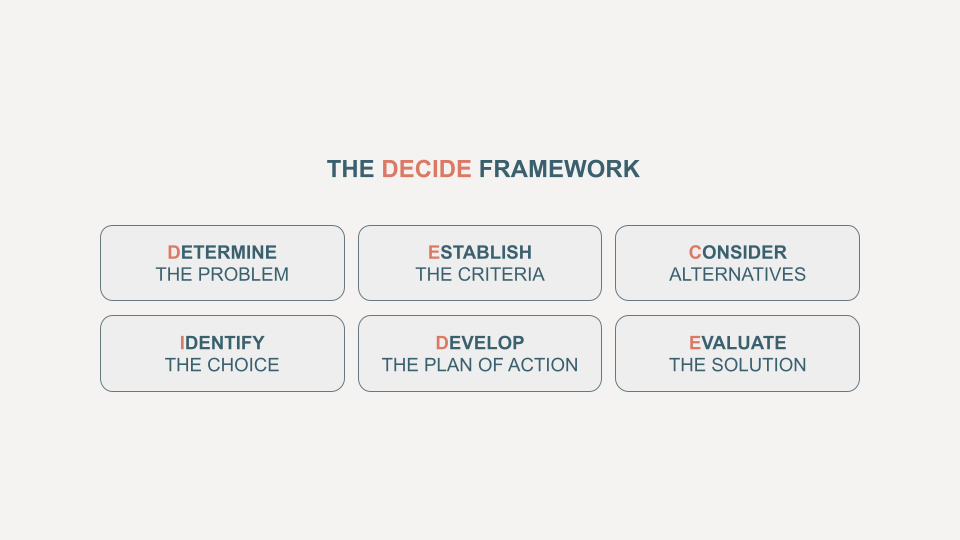

The DECIDE framework was designed in 2008 by Professor Kristina Guo. It’s super simple to memorize and apply.

- Define the problem. Taking a step back to ensure you really understand the problem at hand should be the first priority when trying to make a decision.

- Establish the criteria. If you’re about to purchase a piece of software, what are the criteria? Is it price, great support, ease of use? List all the factors you want to consider before making a decision.

- Consider the alternatives. Try to spend the right amount of time on this step. Too much time spent considering all the alternatives can drive to overthinking and analysis paralysis. Just make sure you have done enough research to have a few solid alternatives.

- Identify the best alternative. Weight the list of criteria you have created in the second step, and rate each of the alternatives. Then, compute the result to see which alternative makes most sense based on your criteria.

- Develop and implement a plan of action. Time to act on that decision. Especially if you have a maximising thinking style, it’s important to force yourself to not go back to the previous steps and to move forward with the decision.

- Evaluate the solution. In order to make better decisions over time, examine the outcomes and the feedback you get.

This is just a framework. To be applied properly, you also need to create the right conditions to encourage smart decision-making.

Thinking clearly and logically takes time. Studies show that people are more likely to make risky choices under such time pressure. So if it’s an important decision you need to make, it can be worth pushing back to ensure you have enough time to consider the potential outcomes.

And remember that, ultimately, most of what we learn is through trial and error. Bad decisions can lead to good mistakes, provided that you take the time to reflect, learn, and adjust your trajectory accordingly.