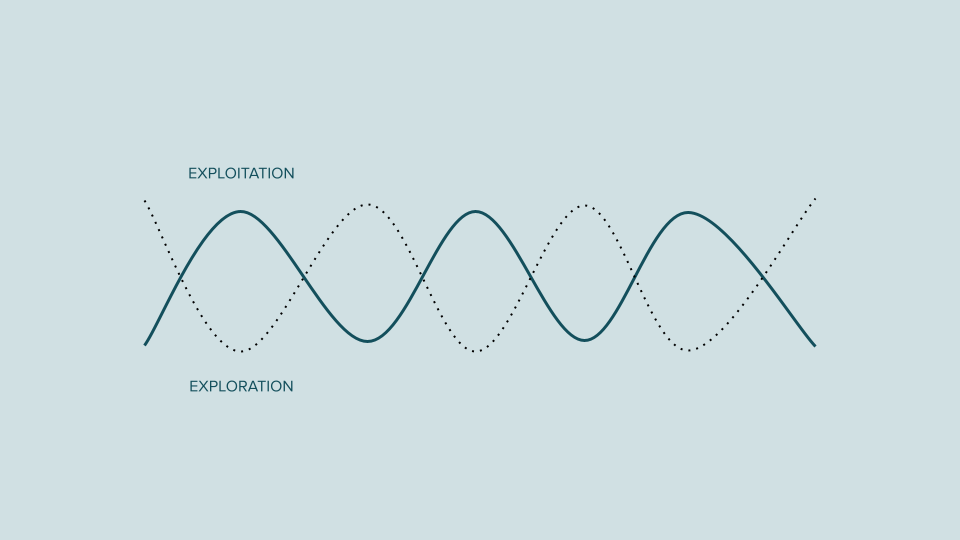

People who can both innovate and optimize are an extremely rare breed. Innovating requires a taste for risk taking and experimentation; optimizing calls for an altogether different skill set, mostly reliant on refinement and efficiency. That’s known as the exploration-exploitation dilemma.

Great innovators are not always great managers. This is a common story: a founder launches a startup, successfully grows it through the initial stages, then gets replaced by a more experienced CEO before the initial public offering. When Professor Noam Wasserman analyzed 212 American startups, he found that a whooping 50% of founders were no longer the CEO.

However, it is possible to cultivate an ambidextrous mindset, where exploration and exploitation go hand-in-hand to produce the best results over the long run. What’s the difference between exploration and exploitation, and how can they be balanced to foster leadership that’s both innovative and efficient?

The difference between exploration and exploitation

In 1976, Professor Robert Duncan from Northwestern University published a paper titled The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. In this paper, he articulates the challenge faced by all organizations: navigating the tension between innovation and efficiency. While running the day-to-day of an organization requires well-defined processes, innovation is more likely to sprout in an experimental environment.

Much later, in 1991, Professor James March from Stanford University further extended Duncan’s theory by defining “the relation between the exploration of new possibilities and the exploitation of old certainties in organizational learning.”

This is how he described the difference between exploration and exploitation:

- Exploration: in this phase, the focus is on experimentation, risk taking, discovery, and innovation. People who excel at this stage are usually more flexible and more comfortable with uncertainty.

- Exploitation: the focus is on execution, refinement, and efficiency. People who are most successful at this stage are usually good at weighting options and making optimal choices.

While startups are in the exploration phase, they usually switch to the exploitation phase when they become mature businesses. As we’ll see, this switch—especially when combined with the unwillingness to switch back to exploration mode when needed—can be a costly mistake.

Avoiding the success trap

Many organizations focus on the exploitation of their historically successful business activities, neglecting the need to experiment and explore new territory to enhance their long-term success. Instead of acquiring new knowledge, these organizations spend all their time and energy on refining their current knowledge through incremental improvements.

Famous examples of organizations that fell prey to the success trap include:

- Polaroid. In the 1990s, the company failed to respond to the transition to digital photography, and persisted in improving their analog products—despite the many obvious signs of the rise of digital technology. While the company still exists thanks to its household brand, it has never again reached its peak revenue of $3 billion in 1991. Another company that famously failed to switch from exploitation to exploration in the digital photography world is Kodak.

- Caterpillar. Both after World War I and World War II, the company struggled to adapt from a wartime economy (where they had many lucrative contracts with the government) to a peacetime economy. As a result, management had to make the difficult decision of restructuring the company and closing many facilities. It’s only when they decided to explore new industries such as construction and agriculture that the company started thriving again.

- Blockbuster. Perhaps one of the best examples, Blockbuster was an ubiquitous provider of home movie and video game rental services in the United States. Today, only one franchised store remains open. Why this spectacular failure? You guessed it: instead of reacting to the rise of mail-order and video-on-demand services by switching to innovation mode, the company kept on trying to exploit its existing position in the market. That’s why today you watch your favorite movies on Netflix, and not on Blockbuster.

To ensure long-term success, leadership needs to achieve a constant balancing act between exploration and exploitation. While it’s tempting to go all-in on exploitation when a company has found product-market fit, it’s crucial to remember that this fit is temporary, and to keep on allocating some research and development resources to encourage exploration.

How to cultivate an ambidextrous mindset

While the concepts of exploration and exploitation have originally been described in the context of organizationational management, their definitions have been expanded to include all levels of leadership, including the individual level. Cultivating an ambidextrous mindset consists in maintaining balance between exploration and exploitation so you don’t fall into the success trap.

The first step is to conduct an ambidexterity audit: how much time, energy, and money are you dedicating to exploration compared to exploitation? It is fine if they are not perfectly balanced, as some phases of business growth or personal development call for more exploration or more exploitation; but you need to ensure you are not dedicating 100% of your resources to one or the other.

Another question to ask yourself is: how easy would it be to switch from one mode to another? The problem with big corporations is that even when management agrees it would be beneficial to foster more innovation, rigid processes and legacy policies can get in the way of switching back to exploration mode. Tackling these challenges before it’s too late can mean the difference between life and death for a business.

At an individual level, you can also inject more flexibility into your processes, so you can easily go from exploration to exploitation—and vice and versa—as needed based on your current goals. Does your schedule allow for serendipity? Are your tools able to support both exploration and exploitation? Some easy changes in your processes can make your life much easier when you get to a point where it’s time to switch gears.

Neither exploration or exploitation are inherently more powerful than the other. The key to an ambidextrous mindset and to long-term success is to balance the two, so you can both exploit the fruits of your existing business, and explore new avenues of innovation to adapt to an ever-changing context.