When I was in uni, we had to attend a series of workshops designed to improve our career prospects. We were supposed to learn how to create a resume, how to use job boards, and lots of other useful skills. At the beginning of the very first session, the instructor gave us a long personality test to fill. It was the MBTI questionnaire, short for Myers–Briggs Type Indicator.

I got INTJ, which stands for Introverted, iNtuitive, Thinking, and Judging. As I read the description (“a scientist with exceptional ability to turn theories into action, a natural leader with very high standards for their performance”), I thought, wow, that’s great. Then, I turned to a friend and asked to read what theirs said. They got ESTJ, for Extroverted, Sensing, Thinking, and Judging. “Dedicated, direct, honest, loyal, patient and reliable, driven by a strong sense of ethics,” it read, and I thought, well, that’s also great. As I read the results of my classmates, it started feeling a bit like astrology, where whatever you read always kind of makes sense.

A few years later, when I joined Google, I took the test again as part of a team building exercise. This time, my result was ENTP, which stands for Extroverted, iNtuitive, Thinking, and Perceiving. And, lo and behold, I really liked the description too!

Since then, I’ve seen many people mention the MBTI in their online profiles and in conversations. Each year, 3.5 million MBTI tests are administered. Businesses have been using the test to make hiring decisions. There are even meetup groups for people with the same MBTI profile, such as Toronto INTJs.

The problem? The MBTI is bullshit.

The story of the MBTI

In 1917, Katharine Cook Briggs met her future son-in-law, and noticed how different his personality was from other family members. She could have stopped at this incredible realisation, but she embarked on a journey of reading biographies of famous people, and developed a typology of four main personalities: thoughtful, spontaneous, executive, and social.

Later, when Jung’s book Psychological Types was translated into English, she decided to turn her previous research into something more practical. With the help of her daughter, she published the The Briggs Myers Type Indicator Handbook in 1944. The handbook attracted the attention of several well-placed people in education and psychology, and was extended upon in 1962.

The most important element to note is that neither Katharine nor her daughter Isabel were formally trained in the disciplines of psychology and psychometric testing. They designed their test by reading biographies and Jung’s work. And, as you’ll see, this doesn’t make for a scientifically solid system.

A so-called scientific approach to personality testing

There are many problems with the MBTI test. Plus, most of the studies that support its scientific validity have been poorly designed or funded by institutions with a conflict of interest. I’ll get a bit more into that, but first, let’s have a look at five reasons why you should not take the MBTI seriously.

- Poor validity. The MBTI test has zero predictive power. The way to validate a scientific theory is to formulate a hypothesis, then carry out experiments or empirical observations to test your predictions. But all solid studies found the MBTI to not be a remotely decent predictor. Put simply, you cannot predict someone’s behaviour or personality using the MBTI test.

- Poor reliability. Remember how I got different results when I took the test a second time? This is the case for most people. Research shows that between 39% and 76% of people taking the test on different occasions get different results, even just after five weeks.

- No evidence for dichotomies. The categories measured by the MBTI test are not independent, and some have even been found to be correlated to each other. Why can’t you be “judging” and “perceiving”, “thinking” and “sensing”? Why does it have to be one or the other?

- Lack of objectivity. According to the manual created by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers, the accuracy of the MBTI depends on “honest self-reporting.” In other tests, the relationship between the test items and the traits measured is not obvious, which makes it hard for the person taking the test to deliberately tailor responses to achieve a preferred outcome. But the MBTI doesn’t take into account our tendency to give socially desirable answers to questionnaires.

- Not comprehensive. Finally, the MBTI paints an incomplete picture of the human personality. For example, it doesn’t consider some traits such as emotional stability—also called neuroticism—which has been shown to be a predictor of depression and anxiety disorders.

But companies selling the MBTI say there is research to back it up. What about this research?

Well, most of the positive research on MBTI has been done through the Journal of Psychological Type, which is owned by The Center for Applications of Psychological Type.

What’s the issue? The Center for Applications of Psychological Type was founded by Katharine Cook Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers. How convenient is it that all the research they publish in their own journal shows that the MBTI is scientifically supported?

In fact, it has been estimated that between a third and a half of all the published material on the MBTI has been produced for the special conferences of the Center for the Application of Psychological Type or as papers in the Journal of Psychological Type. Both are funded by sales of the MBTI and provide paid MBTI training. Let that sink in. Hard to produce research that is more biased than that.

The Barnum Effect

The content itself is not even that practical or useful. In fact, it could apply to anyone. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica:

“The Barnum Effect is the phenomenon that occurs when individuals believe that personality descriptions apply specifically to them, despite the fact that the description is actually filled with information that applies to everyone.”

The Barnum Effect was coined in 1956 by psychologist Paul Meehl who related the vague personality descriptions used in certain psychological tests to those given by famous showman P. T. Barnum. The same effect is used when writing horoscopes to give people the impression that they are tailored specifically to them.

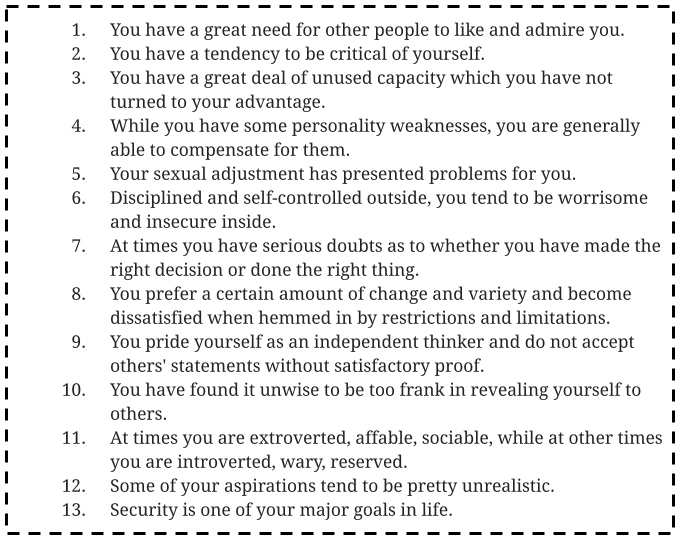

It’s also sometimes called the Forer Effect, after psychologist Bertram Forer. In 1948, he gave a fake psychology test to 39 of his psychology students. One week later, Forer gave each student a purportedly individualised results sheet, and asked each of them to rate it on how well it applied. In reality, each student received the same results, consisting of the following list:

These fake results were put together by Forer by assembling various bits of copy he had found in a newsstand astrology book. How did students rate them in terms of how well it applied to them? Well, the students rated their accuracy as 4.3 out of 5 on average.

The MBTI uses similar techniques, which explains why many people tend to find the results comforting and accurate. It’s a great feeling to read good things about oneself—and again, all the MBTI profiles are positive—and to have a supposedly scientific test validate our personality. And this is probably why, despite the lack of evidence supporting the validity of the MBTI, millions of people keep on taking the test every year.

Now that we’ve established that the MBTI is bullshit, what tests can you use if your goal is to better understand your personality?

More valid alternatives to the MBTI

If you do want to take a personality test, here are two that have been extensively researched and have been found to have both scientific validity and reliability.

The Sixteen Personality Factor Questionnaire. The 16PF for short is also a self-report personality test. The difference is that it has been developed over several decades of actual empirical research by two trained scientists and has been proven a solid tool to measure anxiety, emotional stability, behavioural problems, as well as a way to help with career selection. It takes between 35 to 50 minutes to complete.

The Revised NEO Personality Inventory. Contrary to the MBTI, the NEO PI-R has been extensively tested for reliability, with high consistency when people would retake the test. Furthermore, the psychometric properties of the NEO PI-R have been found to generalise across ages and cultures. It has been used to predictability measure things such as burnout or GPA—a study even found the NEO PI-R to be a better predictor of GPA than SAT results alone.

That being said, if you’re not currently struggling with your mental health, the best way to understand yourself better is still to build a mental gym: making time for reflection, writing, learning something new and getting creative. These activities will teach you much more about yourself than any test you can find on the Internet.