Mental maps, cognitive maps, mind maps… Scientists and popular psychologists alike have coined all kinds of thinking maps. What’s the difference? While it may be tempting to consider some of these maps more effective than others as thinking tools, the reality is that we need a collection of maps in order to make the most of our mind: we need to build a mental atlas.

“The earliest maps are thought to have been created to help people find their way and to reduce their fear of the unknown. (…) Now as then, we record great conflicts and meaningful discoveries. We organise information on maps in order to see our knowledge in a new way. As a result, maps suggest explanations; and while explanations reassure us, they also inspire us to ask more questions, consider other possibilities.”

Peter Turchi, in Maps of the Imagination.

Levels of thinking in maps

While there are many ways to think in maps, an easy rule of thumb to think about these is to use a hierarchy, going from the most geographical to the most metaphorical maps.

Mental maps. Mental mapping is studied in the field of spatial research, more specifically behavioural geography. Mental maps are imagined maps of an individual’s vision and perception of the geographical world. Mental maps are never objective, and this is exactly what makes them interesting. If you ask two people to draw a map of an area from memory, you will obtain very different results. For instance, a child may visualise their house as bigger as the other houses in the neighbourhood; or your mental map may put more emphasis on a road you take every morning to go to work.

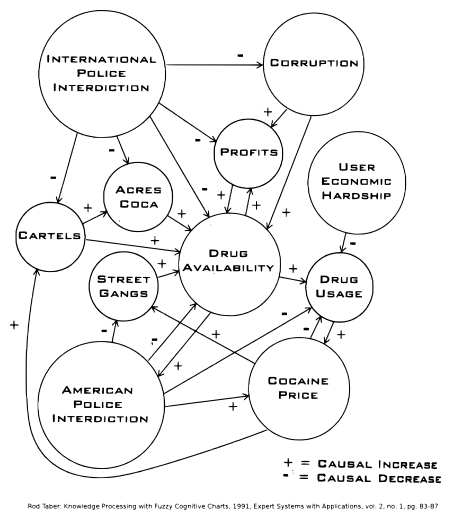

Cognitive maps. Introduced in 1948 by psychologist Edward Tolman of the University of California, Berkeley, a cognitive map is our mental representation of our physical or psychological spatial environment. Cognitive maps are used to encode and recall the attributes and relative positions of pieces of information. They are often used for system modelling or as a decision-making support tool.

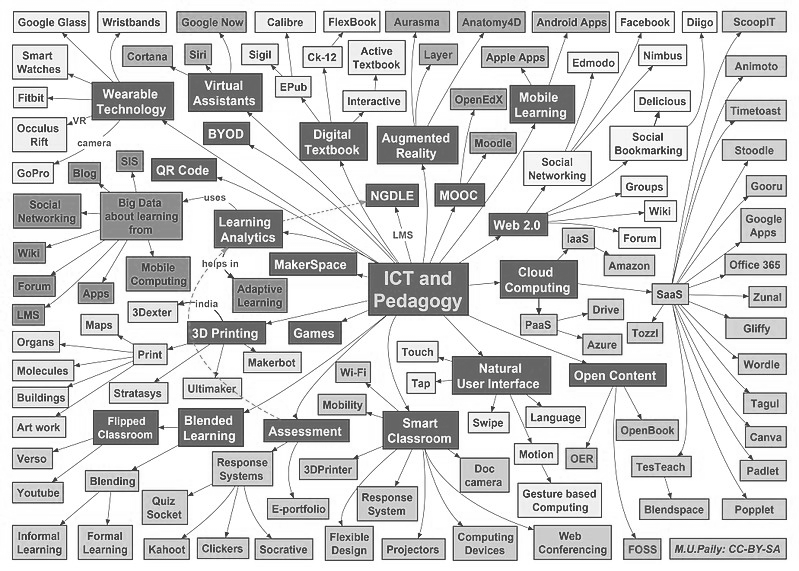

Mind maps. More recent—or at least the term to describe it, which was coined by popular psychology author Tony Buzan in 1974—a mind map is a form of visual map, which starts with a word in the center, and branches out to explore related ideas.

Concept maps. More complex than mind maps, concept maps were developed as a way to enhance learning. They feature bi-directional links and linking phrases such as “influences”, “contributes to”, “requires”, etc.

As you can see, these range from the geographical to the conceptual. Mental maps, while distorted by personal perception, are based on geographical features from one’s environment. Cognitive maps are information-agnostic, including the way we navigate our world as well as our thoughts. Mind maps and concept maps are two additional approaches to represent our mental models.

Building a mental atlas

While there is definitely a progression from the geographical to the metaphorical, it is not to say that some maps are more useful than others. Rather, in order to navigate the world, we need a book of maps—a mental atlas.

The first use of the word “atlas” to refer to such a collection of maps dates from 1595, when geographer Gerardus Mercator’s Atlas Sive Cosmographicae Meditationes de Fabrica Mundi et Fabricati Figura (“Atlas or cosmographical meditations upon the creation of the universe, and the universe as created”) was published posthumously by his son Rumold Mercator. (Gerardus went into creating the famous Mercator projection)

A mental atlas is not just a way to think; it’s a way to explore. Interconnected maps form a dynamic, ever-evolving system where new information and new questions ripple across your internal web of thought to re-shape your beliefs.

The same way a traditional atlas can be easily consulted, so a mental atlas should be. To reduce your cognitive load—specifically your extraneous cognitive load—visual thinking tools such as mind maps and concept maps may be helpful. Building a knowledge graph of your mental atlas will make it even easier to create and rediscover links between ideas and concepts.

Building a mental atlas is a highly personal and intimate endeavour. As Peter Turchi puts it: “We believe we’re mapping our knowledge, but in fact we’re mapping what we want—and what we want others—to believe.” There is no recipe to figure out exactly how to organise and connect your thinking maps together so they are easy to access and explore. However, a few tools offering bi-directional linking may make it easier, such as Roam Research or one of its open source alternatives.

Furthermore, building a mental atlas is a life-long commitment. “The purpose of such mapping isn’t necessarily to recognise and then sustain those patterns or to recognise and then depart from them. Rather, the goal is to recognise unconscious constraints so that we can make conscious choices,” explains Peter Turchi about writing fiction. This holds true for building a mental atlas. While it may be possible to go through life without ever paying attention to these patterns across various mental and cognitive maps, being aware of the inherent interconnectedness of our thoughts will help guide your daily and long-term decision-making process.