Update: This article I wrote in 2019 has become the basis for a book! Order your copy of Tiny Experiments to learn how to apply those principles.

According to Marty McFly in the classic 1985 movie Back to the Future, “If you put your mind to it, you can accomplish anything.”

Now that we live in the future, in a world where there is more information available at your fingertips than you could ever consume, at a time where it only takes a click to pick the brains of the most brilliant experts of our era, it can indeed seem like anything is possible. One just needs a bit of imagination and determination.

Why is it then that we struggle so much to accomplish our goals? That we start many projects but only finish a few, if any? That we spend so much time procrastinating instead of learning and creating?

And why do 92% of people never achieve their New Year’s goals while others seem to more easily manage to stick to their plan?

Some will sign up to an online course and finish it in a few months, then build their first web application, while others will announce every six months that they are going to start studying Spanish again.

Some will take some cooking classes and invite you every week to try their new, improved recipes, while others will get a gym membership and stop going after a week.

My theory is that it’s all about having the right or the wrong mind frame—sometimes called “mindframe” in one word or “frame of mind”—for the task. You can have the best tools and strategies, but if you don’t have the right mind frame, things are not going to work.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a mind frame is a mental attitude or outlook. It’s more than just a mood, it encompasses the particular way someone thinks or feels about something, and deeply influences one’s behaviour.

What I find interesting is that mind frames are always presented as states in which the individual is bound to be. A mind frame seems to be a passive state.

It influences how the individual thinks and acts, but we rarely discuss how the individual can influence their mind frames.

And this may be what is wrong with our approach in setting, managing, and achieving our goals. Instead of shaping our mind frames in a way that plays in our favour and makes it easy for us to progress and feel fulfilled, we see positive mind frames as lucky aids, and negative mind frames as inevitable obstacles.

Seeing it through

Like most people, there are many areas of my life where I would like to improve. But there’s one thing I’ve become better at: finishing what I started.

Mindframing is a word I made up to describe the process I use in many aspects of my life in order to see things through. It’s all about shaping my mind frames to achieve my goals.

While you could probably apply it to literally any area of your life where you’d like to grow, even personal aspects, I find it particularly useful for learning and creating.

It’s a bit of a work-in-progress framework for studying how to grow as a person, and, if you find it useful, a flexible tool for creative people that want to grow through learning and making.

As I use it everyday, it keeps evolving, but you may find it a solid methodology to achieve more and finish what you started.

(quick note that this is obviously not a behavioural therapy framework that would address any underlying mental health issues you may be struggling with)

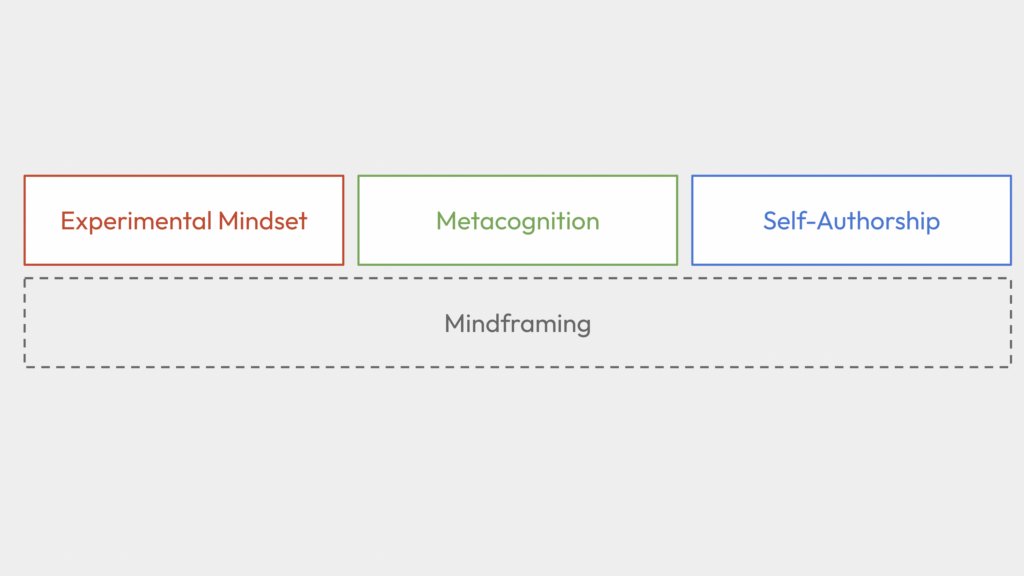

There are three main frames to consider to become a “master mindframer”:

- Experimental mindset

- Metacognition

- Self-authorship

Having an experimental mindset means having the willingness to experiment and the deep belief that growing happens through small, incremental steps, rather than big overnight victories. There is a great article by Steph Smith, a fellow maker, about “the sequences of events that seem minimal at each juncture, but compound into major gains.”

It also means embracing failure as part of the process—knowing that even though you have ups and downs, even when learning something new or building a product takes longer than expected, or doesn’t go as planned, you are able to trust the process and keep on adding new building blocks to your Lego castle every day.

The second mind frame is metacognition. Sounds like a hairy word, but it’s not. Metacognition is simply “cognition about cognition”, or simply put “thinking about thinking.” It’s a higher-order skill that allows you to be aware of your own awareness.

Metacognition is your knowledge of what you know and don’t know, as well as all the strategies you use for learning and problem-solving. Mnemonic techniques, study plans, productivity tricks, or even how difficult you perceive a task to be, are all part of metacognition.

The metacognition mind frame means that you make an effort to stay aware of how you understand, retain, and reuse new information. It also means that you are able to use this awareness to enhance the way you learn and grow, by fixing or optimising your approach.

Finally, self-authorship is the ability to define and express your own personal authority. It means that you’re not relying on external authority to define your beliefs, values, and social relationships. Instead of relying on external formulas, you are able to rely on your own internal voice to make decisions on a daily basis.

At a deeper level, self-authorship means that even though reality is out of your control, you know you can control how you react to it and that you can shape your mind frames and reactions to external events. When on a journey to learn something new and grow, this is essential to stick to your plan despite, you know, life.

Having an experimental mindset, metacognition, and self-authorship are crucial to mindframing so you can see your projects through. I could write a ton more about these mind frames in this article, but I’ll try to keep it short.

A personal growth framework for makers

Learning frameworks are fascinating and can get pretty complex. I mean, look at the Learning Compass from the OECD, which “defines the knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that learners need to fulfil their potential and contribute to the well-being of their communities and the planet.” And we can’t really blame them: there is a lot to personal growth and education. It’s hard to encompass everything in one pretty framework.

What I like about mindframing compared to other learning frameworks I’ve tried is that it really encourages you to make—to produce content, build applications, and in short apply what you learn as soon as possible to solidify it. It’s more of a making framework.

First, let’s have a look at the tools you need. Many frameworks “require” to buy this special notebook or whatever tool will make you more productive. For mindframing, you just need something to write. I use a combination of a notebook and just my text editor.

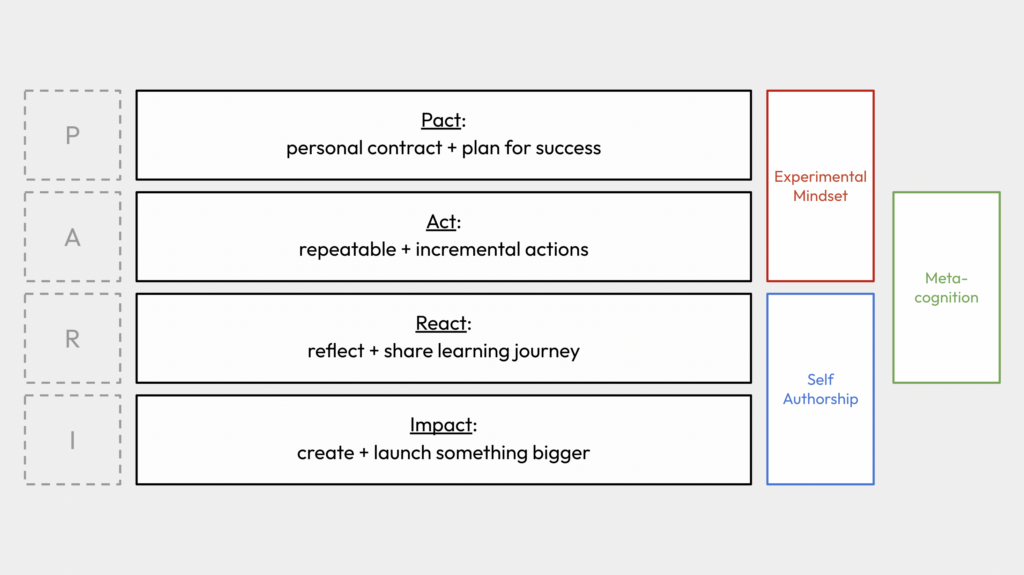

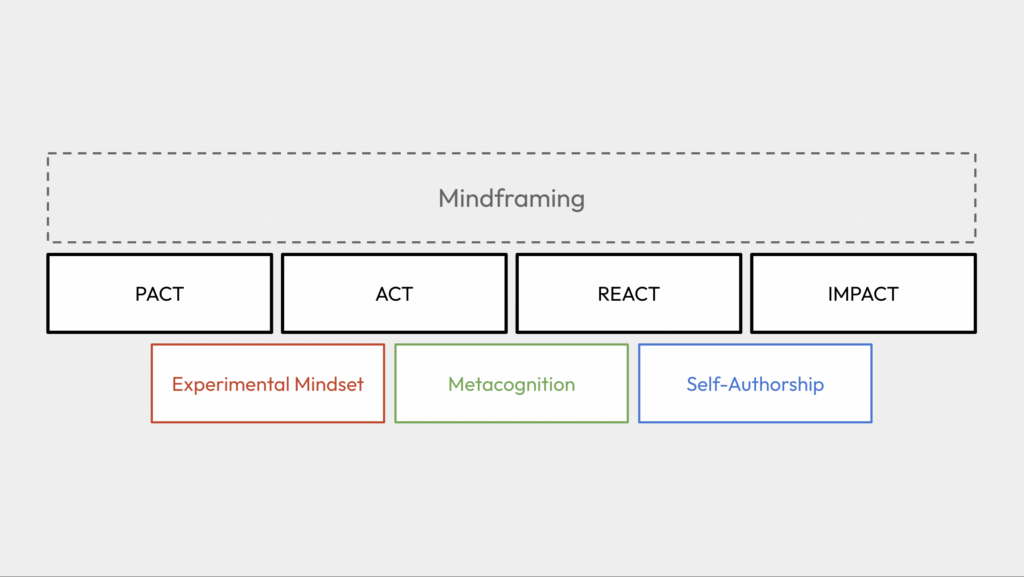

There are four steps to the mindframing method:

- Pact

- Act

- React

- Impact

Which, you may notice, conveniently spells out PARI, which means “bet” in French. Now, let’s go through each of these briefly.

First, you create a pact, either with yourself or with others. I’m personally a big proponent of learning and building in public, but if you feel like you have the mental resilience and emotional strength to keep yourself accountable without sharing your goals with others, that’s fine too. There are also cases where you may not want to build your product in the open for other practical reasons.

A pact—which I could have called a contract, but CARI doesn’t mean anything in French—means in this case that you are committing to regularly spend time working towards your goal. It does not define the nitty-gritty of what you will do, or how long each session needs to be, just that you will be dedicating time on a regular basis to actions that will make you progress towards that goal.

A great example is #100daysofcode. Code newbies make a public pact to code every single day for a hundred days in a row. It does not matter for how long, what exactly they will do—it could be following a tutorial, building a small thing, reading some documentation, reaching out to a mentor with some questions—but they need to do at least one thing every day that contributes towards their goal of learning how to code.

Second, you need to act. This is usually the hardest part in most learning frameworks, which are complex and require you to go through lots of content in a specific order, study for a predetermined amount of hours per week, then complete some specific assignments. Way to feel discouraged.

With mindframing, you are in control of your learning process. The only thing you could do wrong is to do nothing. Open a book and read one page? That’s progress. Watch a tutorial video? That’s awesome. Listen to a friend sharing their thoughts about a coding event they attended? That counts too. There is no small contribution towards your goal. Each step you take brings you closer to the person you want to become.

Third, you need to react. This is when you start really internalising the concepts you have previously engaged with by creating your own content. I know it can sound daunting to start producing content at this stage. You feel like you’re such a newbie—who are you to share your thoughts about a topic that’s so new to you?

But this is one of the most efficient ways to learn, with the added bonus of helping you connect with people who are also interested in the topic. This could take many forms: a blog post, a short podcast, a live stream, a thread on Twitter, an email to your list. This article is actually me consolidating lots of the stuff I’ve been learning in the past years. Reframing and explaining your thoughts to someone is a great way to consolidate yours.

Finally, you need to work on a project with impact. Once you feel familiar enough—which means that you can grasp the concepts and can articulate them, but still feel very uncomfortable using them—you should start creating something bigger. If you’re learning how to code, time to try building your first complex application. If you’re studying ancient history, time to write longer essays about a little-studied topic and submit them to relevant publications. If you’re studying music composition, time to create a collection of original pieces.

These will probably not be very good at first, but you will learn an incredible amount by pushing yourself to not only be able to explain concepts, but by having a deep enough understanding to create something of your own.

Pact, act, react, impact. That’s it. Just four steps that can bring you from “I have no idea what I’m doing” to “I’m actually creating something based on what I learned”—which is pretty cool.

For each step, you will need a combination of an experimental mindset, metacognition, and self-authorship.

This is just my framework. It helped me learn how to code and study neuroscience while running my business without losing my sanity, but it may not work for everyone. In the end, it’s all about finding the strategies that allow you to grow and feel fulfilled. Remember, self-authorship is key!