“It’s not rocket science!” people often say. Well, sometimes, projects can be so complex, making the right decision does feel akin to rocket science. Who better to turn to than one of the biggest space agencies in the world to learn how to manage risk? There are few organisations working on projects as complex as the ones NASA deals with.

NASA is known to have a process for everything. They use a standardised test to measure creativity, have detailed checklists for each project, and have developed what they call the Risk Matrix to identify and manage risk.

Uncertainty raises our stress levels, which makes us more prone to mistakes. Instead of trusting our brains, a matrix is a simple and powerful tool which offers scaffolding for decision-making in complex situations. For instance, the Eisenhower matrix of prioritisation helps decide what to work on next based on the importance and urgency of an action item. The NASA Risk Matrix—also called risk scorecard—helps determine the level of risk associated with a particular situation, and decide how to react.

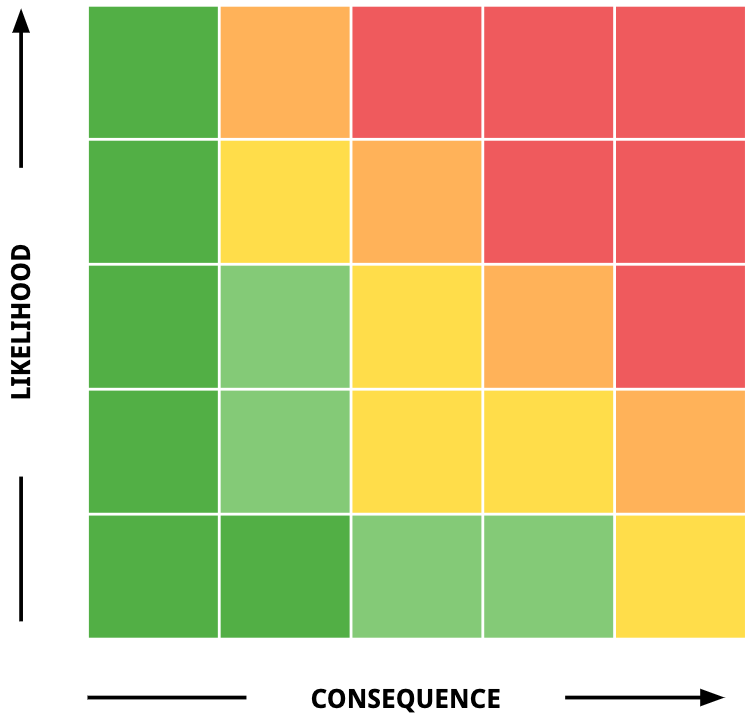

In their own words, the NASA Risk Matrix is “a graphical representation of the likelihood and consequence scores of a risk.” The Guidelines for Risk Management document outlines how to use the Risk Matrix for risk management. But first, you need to identify and clearly state a potential risk.

“Progress always involves risks. You can’t steal second base and keep your foot on first.”

Frederick Wilcox.

How to clearly state a risk according to NASA

NASA recommends to keep it factual and to stay away from trying to provide a solution. At this stage, your only goal is to state the risk in an easy-to-understand way, using the following template:

Given that [CONDITION], there is a possibility of [DEPARTURE] adversely impacting [ASSET], thereby leading to [CONSEQUENCE].

- Condition. The current key fact-based situation that is causing you concern, uneasiness, doubt, or anxiety.

- Departure. The undesired potential change from the original plan, which is made more likely as a result of the condition you identified.

- Asset. The project affected by the risk you identified.

- Consequence. The potential negative impact the risk can have on the asset.

For instance, let’s say you are creating an ebook, and working with an illustrator to design some graphics to go along the copy. The illustrator gets sick, unable to work for a week, and you need to communicate the risk of a delayed launch to the rest of the team:

“Given that the illustrator is still on sick leave, there is a possibility of a delay in the illustration work adversely impacting the ebook design process, thereby leading to pushing back the ebook launch by at least one week.”

Of course, you don’t need to communicate this formally in all uncertain situations, but making sure all the key information—condition, departure, asset, consequence—are included in your risk statement will make it easier for people you collaborate with to understand the risk you worry about.

In addition to the risk statement, it is also helpful to include the key circumstances around the risk, the contributing factors, and related information such as what, where, when, how, and why. NASA calls all this additional information the context statement. “The context statement should include only facts, not assumptions. Ensure that no new risks are introduced here,” they explain.

What is missing from the risk statement and the context statement is a risk quantification: how likely is the consequence of the risk? For this, we need to turn to the NASA Risk Matrix.

Using the NASA Risk Matrix to quantify risk

There are two main factors impacting any level of risk: how likely the potential departure is to happen (the likelihood) and negative the impact of the departure from the original plan would be (the consequence). The NASA Risk Matrix uses these two factors to quantify the level of risk.

On the y axis, you can see the likelihood, which is rated from 1 at the bottom to 5 at the top. On the x axis, we measure the consequence, which is also rated from 1 on the left to 5 on the right. So how do you rate both of these factors exactly?

For the likelihood score, you estimate how certain you are the risk will materialise.

- Not likely (under 20% probability of happening)

- Not very likely (between 20% and 40% probability)

- Likely (between 40% and 60%)

- Highly likely (between 60% and 80%)

- Near certainty (over 80% probability)

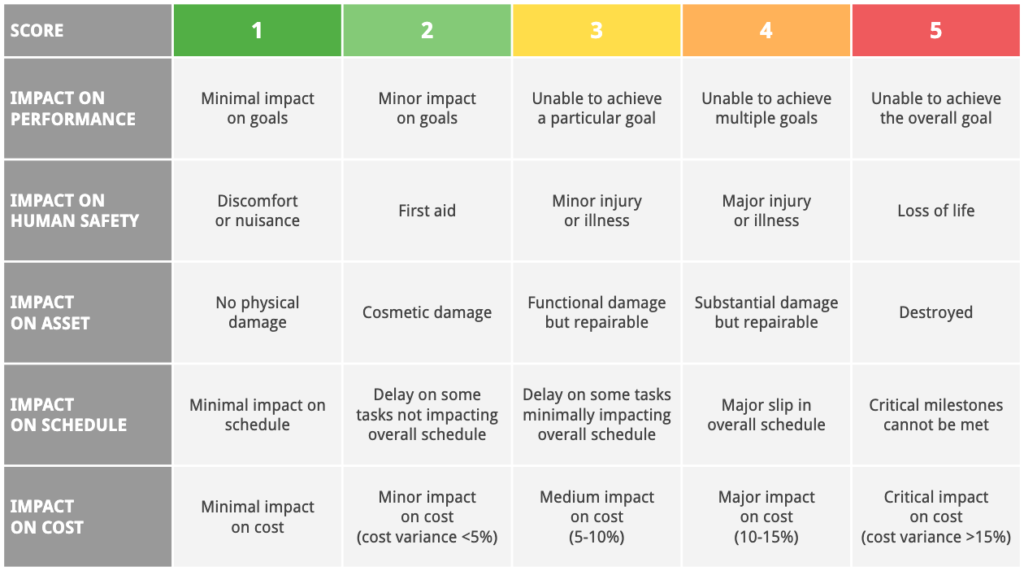

Then, for the consequence score, you use the consequence scorecard:

Obviously, if you don’t work at NASA and need to evaluate risk in daily life, many of these criteria will be over the top. Most of the decisions we make at work don’t involve evaluating the impact of a potential risk on human safety—even though many manual workers do need to consider that criterion on a daily basis.

The consequence scorecard is great to understand the principles behind determining a consequence score. Once you are familiar with it, you can decide on a score based on your expertise and your general knowledge of the project.

Okay, let’s go back to our ebook example:

“Given that the illustrator is still on sick leave, there is a possibility of a delay in the illustration work adversely impacting the ebook design process, thereby leading to pushing back the ebook launch by at least one week.”

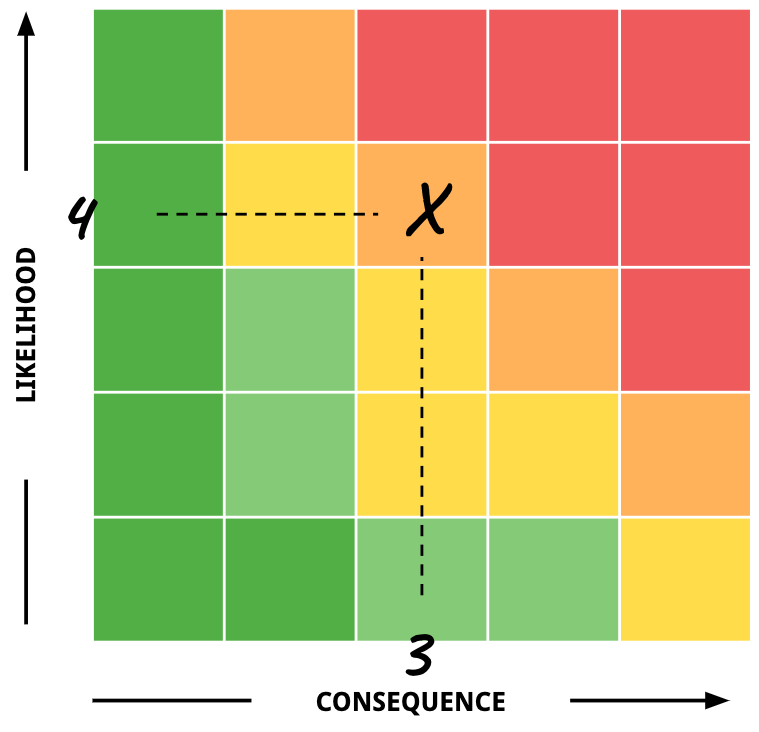

First, what is the likelihood of the illustration work being delayed? Well, the illustrator is on sick leave at the moment. Except if they miraculously feel better tomorrow, the illustration work being delayed seems near certain. But they may feel better quicker than expected, so let’s say it’s very likely the illustration work will be delayed, which would be a likelihood score of 4.

Second, what is the consequence score? Delaying the launch by a week because of the illustration work seems to fit with “Delay on some tasks minimally impacting overall schedule” in our consequence scorecard. So that would be a consequence score of 3.

Pro tip: If several aspects of the project are likely to be impacted, only keep the highest consequence score. For example if you have a minor impact on cost (2) and a major slip in overall schedule (4), the consequence score would be 4.

Now, let’s go back to our matrix and see what a likelihood score of 4 and a consequence score of 3 give us in terms of overall risk score.

It may have not seemed obvious from the initial risk statement, but the illustration work being delayed actually constitutes a high risk situation for your ebook launch. The next step is to mitigate the risk by considering strategies to lower either the likelihood, the consequence, or both.

Mitigating risk based on a specific NASA risk score

We have our risk score. What to do with it? Here is what NASA recommends to do in each situation:

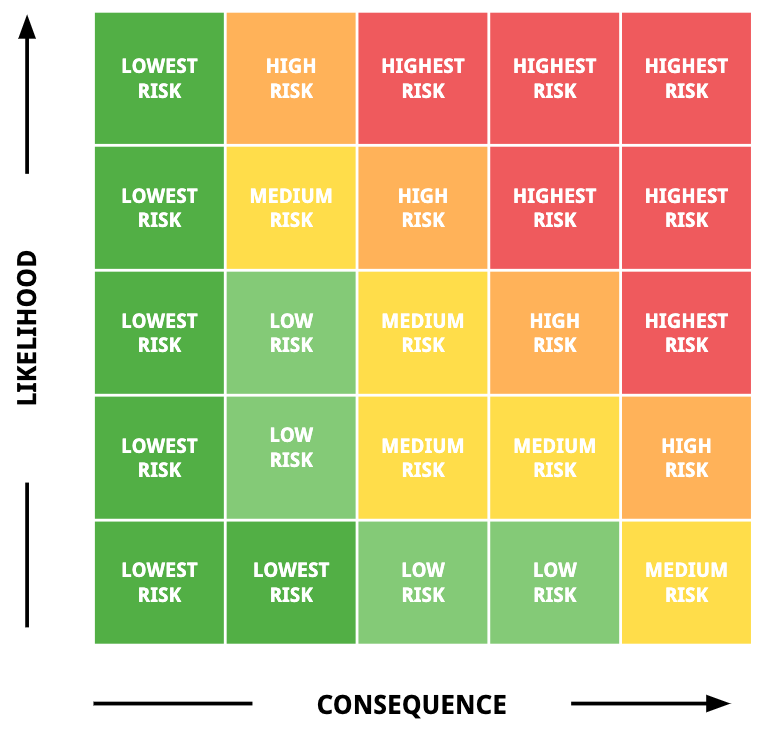

- Lowest risk. This is the dark green area in the matrix. If your risk scores fall in this area, put the risks on a watch list and re-assess them regularly. “There is no specific requirement to generate a mitigation plan. The only requirement is to identify and track the risk drivers to ensure the risk remains tolerable,” says NASA.

- Low risk. Perform extra research to better understand the risk. Write a risk mitigation plan which captures the actions to be taken to reduce the likelihood of the risk happening. Share it with your team so everyone is aware of the plan should the risk happen.

- Medium risk. In addition to writing and sharing the risk mitigation plan, perform continuous risk assessments, and assign adequate resources.

- High risk. Risks that have a high score need to be communicated to the NASA Independent Verification and Validation department. For you, it means high risk situations need to be escalated internally. Don’t keep these just to yourself or your immediate team. Let all relevant stakeholders know about the risk.

- Highest risk. At this level of risk, you and your team may consider considerably changing the original plan. This decision may involve significant costs—in terms of schedule, performance, budget—that may be extremely difficult or even impossible to avoid. Knowing that you are dealing with the highest risk level will help in making hard but necessary choices.

It’s important to note that a mitigation plan can be to not mitigate the risk. For instance, in the case of our ebook, a mitigation strategy could be to hire another illustrator to do the job and launch on time. However, if hiring a new designer significantly impacts the overall production cost of the ebook, and results in much lower margins, it may be a smart decision to just delay the launch.

Again, you will probably not need to follow such a formal process every time you evaluate a risk, but the NASA Risk Matrix is a good mental model to use when facing uncertainty. Study it, make it yours, and use its general principles in complex situations.