Humanity has lived through several cognitive revolutions already. The development of various writing systems around the world; the invention of the printing press; the formulation of the heliocentric hypothesis by Copernicus; Darwin’s theory of evolution; Einstein’s theory of relativity—all of these discoveries have fundamentally reshaped the way we think.

While nowadays the spotlight is on artificial intelligence, space exploration, and other exciting areas of research, another quiet revolution is changing the way we ideate and collaborate.

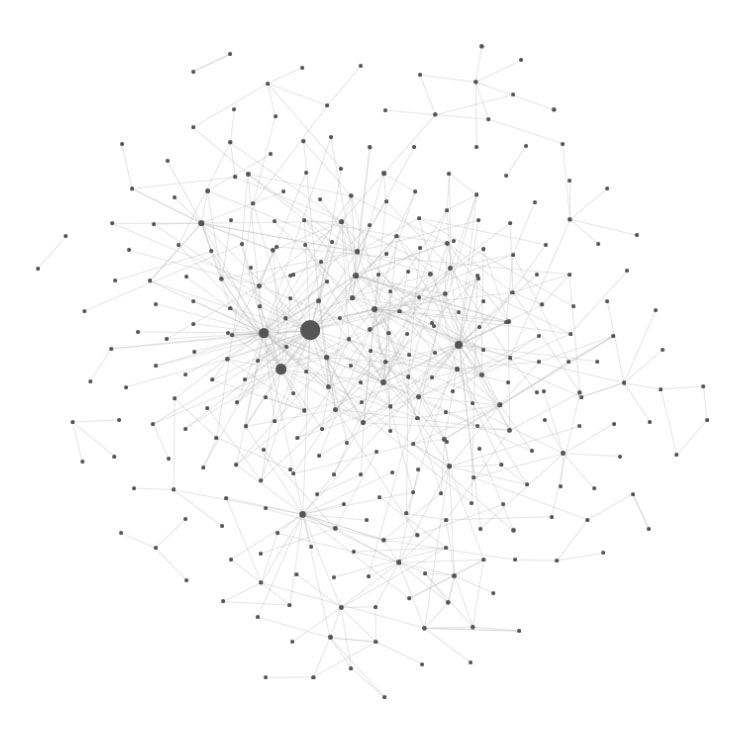

Networked thinking is an explorative approach to problem-solving, whose aim is to consider the complex interactions between nodes and connections in a given problem space. Instead of considering a particular problem in isolation to discover a pre-existing solution, networked thinking encourages non-linear, second-order reflection in order to let a new idea emerge.

Thinking in networks can be done at an individual level, but the power of networked thinking becomes apparent in a collaborative setting, where each individual contributes to the creation of new branches and the addition of new connections between existing nodes.

The unconventional ideas resulting from networked thinking sometimes seem like they fly in the face of common sense. Which is not necessarily a bad thing: common sense has many limitations, and can prevent us from making remarkable—and accurate—discoveries.

The limitations of common sense

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines common sense as a “sound and prudent judgment based on a simple perception of the situation or facts.” Based on heuristics, common sense allows us to make judgments and solve problems quickly and efficiently. But efficiency (doing things in the most economical way) does not equal effectiveness (doing the right things).

Common sense is actually a pretty bad indicator of truth. Because of cognitive biases and preconceived opinions, ideas that sound right are often wrong. “Common sense is actually nothing more than a deposit of prejudices laid down in the mind prior to the age of eighteen,” Einstein presumably said. (rule of thumb: always be skeptical with Einstein quotes!)

Beyond cognitive biases and preconceived opinions, common sense is based on linear thinking. “I experience A, therefore I can directly explain it by B.” However, earth rotating around the Sun goes against our natural intuition; so does the fact that a heavy object doesn’t fall faster than a light one. The Earth appears to be flat; but it’s not. And solid objects are actually mostly made of empty space.

Despite the limitations of common sense, we keep falling into its trap. Take climate change: in a survey conducted in Australia, the participants who thought climate change was not happening or was caused by natural processes were more likely to select “common sense” as the reason for their belief.

Instead of linear thinking, using networked thinking to understand the world is taking a stance against common sense. And it can radically alter the way we approach problems. As John Edward Terrell, Termeh Shafie and Mark Golitko write in Scientific American: “Adopting a networks perspective changes how we see the world and our place in it.”

Networked thinking in science

Humans are social animals. While tools were significant in our capacity to thrive as a species, our ability to collaborate and learn from each other has probably been the underlying skill leading to all of our other skills. “The idea of human as networker is fast replacing the idea of human as toolmaker in the story of the human brain,” write archaeologists Clive Gamble and John Gowlett and evolutionary psychologist Robin Dunbar in the book Thinking Big.

Because of our inherently social nature, our human connections may be seen as an extension of the way we interact with the world. And this view is fundamentally shifting the way we conduct science.

For instance, we used to think that the main cause of obesity was a poor diet at an individual level, leading to treatments focused on the individual. However, taking a networked thinking approach in a 32-year-long study with over 12,000 people led researchers to discover that the participants’ personal network had a great impact on their likelihood to be obese. “Discernible clusters of obese persons were present in the network at all time points,” write the researchers.

The real kicker? “The clusters extended to three degrees of separation.” It means that people who had never met in person were influencing each others’ weight.

Another example concerns the dissemination of ideas. Conventional wisdom suggests that people with stronger ties with others will better disseminate ideas. However, research into interpersonal networks shows that people with weaker ties are better influencers, because they tend to be part of more clusters of people—they are effectively connected to more nodes in the network.

Instead of looking at the intrinsic properties of a specific node to predict outcomes, networked thinking considers the interconnection between nodes to study a problem as an emerging phenomena.

Divergence and emergence

Networked thinking is based on two key principles: divergence and emergence. Starting from any relevant node in the network, the divergent phase consists in branching out from that original point in many directions, without trying to evaluate the validity of any particular idea.

At this stage, each node is basically a question mark, opening the door for further related questions. Similar to the logistic map, where a chaotic behaviour can arise from a very simple non-linear dynamical equation, such a simple iterative approach can lead to the formation of complex thinking maps.

When enough nodes are added to the network, patterns start to emerge. It may be specific clusters, or strong ties between particular nodes. In the example of the obesity study mentioned earlier, researchers noticed clusters of obese people, as well as ties between people up to three degrees of separation.

Divergence and emergence allow networked thinkers to uncover non-obvious interconnections and explore second-order consequences of seemingly isolated phenomena. Because it relies on undirected exploration, networked thinking allows us to go beyond common sense solutions.

Navigating islands of knowledge

Each cluster of nodes in a thinking map is an island of knowledge no longer secluded. The more nodes are added to the network, the bigger the ocean—and the more unknowns are uncovered.

Akin to the infinite patterns of fractals found in natural creativity, such networks of knowledge feed themselves, resulting in repetitive branching. The infinite nature of thinking maps may sound daunting, but that is exactly what makes them such amazing knowledge discovery tools.

“We strive toward knowledge, always more knowledge, but must understand that we are, and will remain, surrounded by mystery. This view is neither antiscientific nor defeatist. Quite the contrary, it is the flirting with this mystery, the urge to go beyond the boundaries of the known, that feeds our creative impulse, that makes us want to know more,” physicist Marcelo Gleiser writes in The Island of Knowledge.

He also writes: “Asking who is right misses the point, although surely the person using tools can see further into the nature of things. Indeed, to see more clearly what makes up the world and, in the process to make more sense of it and ourselves is the main motivation to push the boundaries of knowledge.”

Tools for networked thinking

We are witnessing the advent of a new category of tools for thought that can help us “see further into the nature of things”, in parallel with emerging research in the field of augmented intelligence (also known as cognitive augmentation)—where technology is designed to enhance human intelligence rather than replace it. As often with technology, the excitement precedes the actual fruition, but this quiet revolution is already palpable.

While many of the features of the most recent tools for thought are not new per se, there is an undeniable networked thinking renaissance, spearheaded by Roam and amplified by threaded Twitter. In addition, platforms such as Substack and Patreon are making it potentially sustainable to be a public intellectual, leading to a new wave of “indie thinkers” such as Andy Matuschak, Gwern Branwen, Li Jin, Scott Alexander, David Chapman, and Visakan Veerasamy. Communities like The InterIntellect, Public Platform, and IndieThinkers are proof of this new wave.

The state of current technology greatly impacts our ability to manipulate information, which in turn exerts influence on our ability to develop new ideas and technologies. Tools designed to enable networked thinking are a step in the direction of Douglas Engelbart’s vision of augmenting the human intellect, resulting in “more-rapid comprehension, better comprehension, the possibility of gaining a useful degree of comprehension in a situation that previously was too complex, speedier solutions, better solutions, and the possibility of finding solutions to problems that before seemed insolvable.”

Breaking the mould of categorical thinking, where the goal is to determine fixed boundaries and which pushes us to set arbitrary thresholds for decisions, networked thinking encourages unbounded exploration, where the explorer needs to be comfortable with the idea of not having a specified destination. When it comes to knowledge, there is no “end of the road”—networked thinking is all about embracing the chaotic nature of the journey.