Yesterday evening, Elon Musk gave the first public presentation about Neuralink, a company he founded in 2017 to build brain-computer interfaces. While most of the research in that field has been focused on restoring functionality lost due to paralysis, Elon targets healthy and able-bodied people.

Elon considers that artificial intelligence surpassing human intelligence is not just a probability, but a certainty. Instead of being left behind, he wants to achieve a symbiosis with artificial intelligence.

“With a high bandwidth brain-machine interface, we will have the option to go along for the ride.”

Elon Musk.

Much has been written about the ethical ramifications of brain-computer interfaces—and there’s lots to be discussed indeed in terms of privacy, potential coercion, interaction with a user’s personality, legal responsibility of a user—but here I’d like to explore the potential impact of Neuralink on knowledge work: how we learn, how we communicate, how we create and collaborate.

But first, let’s have a look at what Neuralink is and what was the big presentation all about.

Building on the shoulders of giants

Brain-computer interfaces aren’t new. In 2006, Matthew Nagle was the first person to receive a brain implant allowing him to control a computer cursor with the power of thought. In 2017, Bill Kochevar, who had lost all power of movement, received a similar procedure that allowed him to control his hand with his mind. He became able to eat and drink without assistance.

These brain-computer interfaces are all unidirectional, allowing people to communicate or enabling motor control, but not to receive information. In contrast, Elon’s vision is to make Neuralink bi-directional, becoming a true extension of the human mind by improving our memory, helping us learn, and ultimately making us smarter.

Without going too much into the technical details, there are three main innovations Elon revealed at the event that may bring him closer to his vision:

- Flexible threads that are much thinner than the materials currently used in brain-computer interfaces: these are thinner than a human hair, and offer higher bandwidth, meaning more data from the brain will be able to be picked up.

- A neurosurgical robot capable of safely inserting these threads into the brain: it’s extremely quick, inserting six threads per minute, and is able to avoid blood vessels.

- A sensor device packed with custom chips enabling signal amplification and acquisition: this will allow the computer to receive better quality data from the brain.

Neuralink is currently being tested on mice. In their research paper, Neuralink says they have performed 19 surgeries with its robots and successfully placed the threads 87% of the time. In the Q&A at the end of the presentation, Elon also revealed that “a monkey has been able to control a computer with its brain.” Then he added: “Just, FYI.”

Neuralink is now seeking FDA approval to start clinical trials on humans as early as next year, but let’s explore how a world in which Neuralink becomes reality would look like for knowledge workers.

The way we learn

Learning and memory are two obvious areas that will be impacted by brain-computer interfaces. The US is already working on a programme to enhance learning of a range of cognitive skills in soldiers by encouraging neural plasticity in the brain.

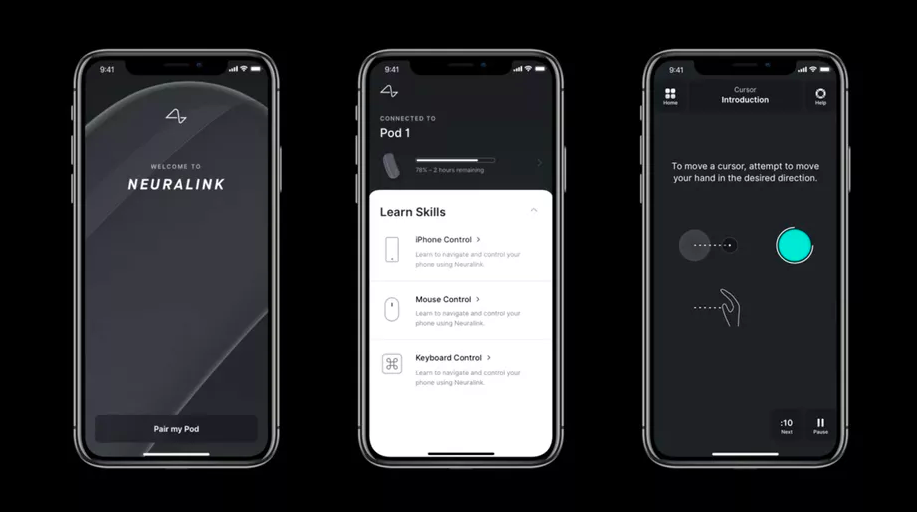

In the first version, Neuralink will be controlled by a mobile app, which means phones are not going anywhere for now. The app will guide users so they can acquire new skills, such as controlling their keyboard or their mouse.

But what about other, more complex skills? Being able to use the Internet efficiently is like having a second brain. A brain-computer interface such as Neuralink, if it achieves bi-directionality, would mean you’d have access to all the public knowledge in the world, at all times, with zero latency.

This interaction could go from simply looking up information using your mind, to just knowing facts as if you had actually spent time studying them. Instead of building supercomputers, this would allow us to become superhumans.

“Us” may not be everyone, though. There is already a persistent gap in educational performance and access to education between socioeconomic groups in many countries. It’s hard to ignore the disparity this future will create between the ones able to afford the technology and the ones who won’t.

I know I said I wouldn’t talk about ethics in this article, but the question of education is particularly important for the future of work.

The way we communicate

From letters, to telegrams, text messages, emails, and then direct brain-to-brain communication, we will have come a long way. But thought communication would probably be very different from regular communication.

“If I were to communicate a concept to you, you would essentially engage in consensual telepathy (…) The conversation would be conceptual interaction on a level that’s difficult to conceive of right now.”

Elon Musk in conversation with Tim Urban.

Forget what you saw on TV with people hearing each other’s voice in their head. The buzzing thoughts in your mind are in no way shaped like the symbols you use to communicate them to others. With an advanced brain-computer interface, you could send your raw, unintermediated thoughts to other people. You could also instantly send someone a picture or a piece of music you’ve been playing in your head.

Another aspect is emotional and sensory communication. You could communicate your emotions and sensory information in a way that’s not possible today. Words are incredibly limited compared to the infinite range of human feelings.

Neuralink could enable super-empathy in human beings by letting them actually feel what another person feels: their emotions, but also what they see, what they hear, the touch of the sun on their skin or the taste of the food they’re eating.

The way we work

These drastic changes in the ways we will learn and communicate in a world where Elon manages to achieve his vision for Neuralink have many implications for the way we work, especially for knowledge workers.

First, let’s talk about creative work. Imagine a world where you can instantly share your thoughts, ideas, sources of inspiration, sounds you heard, or the exact colours and atmosphere you envision with the people you collaborate with. Imagine what a brainstorming session would look like.

Now, remember that everyone would not have to be in the same room. Remote work is in its infancy, but Neuralink would take it to a whole new level. Everyone could be on different continents, communicating their thoughts—their actual thoughts—and what they see and feel in real time.

And of course, the way we work on our own will be radically different. Why have laptops with keyboards and a mousepad when we will be able to directly control the machine with our mind? What will collaboration between a computer and a human brain look like once we go beyond the simple motor actions of moving the mouse or pressing some keys?

The potential impact on the pace of innovation cannot be overstated.

Merging with AI

In the above scenario, we humans still control the machines, albeit in a more efficient way. But Elon’s vision is to merge our brains with AI.

Before this can become a reality, we need to get a better understanding of how the brain works. It’s actually fascinating how little we know today. This is why several governments have been investing in neuroscience research, such as the BRAIN initiative in the US and the Human Brain Project in the EU.

This lack of understanding will give more time to policy-makers, philosophers, and science fiction enthusiasts to imagine and plan for a future where we will be able to instantly download knowledge into our brains, read each other’s thoughts, and collaborate with artificial intelligence just using our mind.

Sources:

- An integrated brain-machine interface platform with thousands of channels (Neuralink’s white paper)

- Neurotechnology, Elon Musk and the goal of human enhancement (The Guardian)

- Neuralink and the Brain’s Magical Future (Wait But Why)

- Brain computer interface learning for systems based on electrocorticography and intracortical microelectrode arrays (Frontiers)