Ask anyone their opinion on one of the many political and ethical divides of the moment, and you will receive a strong opinion as to what “ought” to be. While people tend to appeal to logic to justify their stance, many of these positions are actually guided by their personal values. Our values are our preferences concerning what we consider appropriate courses of actions. They strongly influence our decisions, and yet, very few take the time to wonder: what are my personal values?

The transmission of values

Personal values can be ethical, moral, ideological, social or even aesthetic. They are thought to be transmitted mostly through parenting, but our cultural environment also plays an important role. For instance, ethnotheory research suggests that American parents tend to value intellectual knowledge; Swedish parents value security and happiness; Spanish parents value social skills; Italian parents value emotional abilities and having a balanced temperament; Dutch parents value independence and the ability to stick to a schedule.

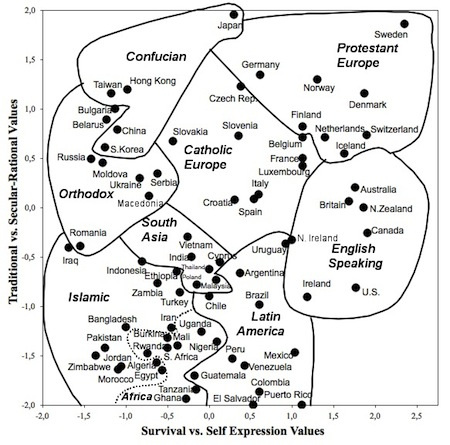

The Inglehart–Welzel cultural map of the world is a scatter plot that shows closely cultural values that vary between societies in two predominant dimensions: traditional versus secular-rational values, and survival versus self-expression values.

Traditional cultures tend to value religion more, while secular-rational cultures tend to value scientific research more. Cultures focused on survival tend to be industrial societies, whereas cultures focused on self-expression tend to be post-industrial societies.

Despite the weight of culture on the way we form our personal values, individuals within each society vary in terms of values and importance they place on specific values. How much their values can deviate from the norm depends on the “cultural tightness or looseness” of the society, explains Pertii Pelto, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Minnesota.

Good and bad values

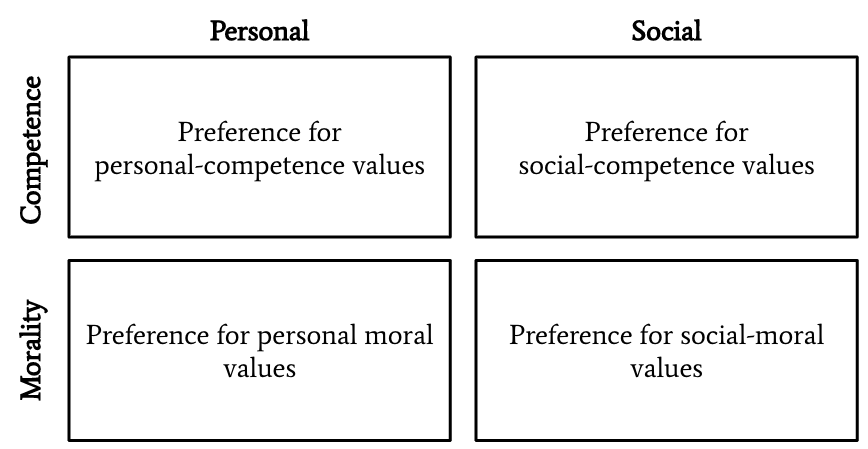

Researchers have identified four different personal value orientations based on our “terminal values” and “instrumental values”. Terminal values are our goals in life—our desirable states of existence. They can be personal (a comfortable life, freedom, happiness, social recognition, true friendship) or social (a world at peace, equality, national security). Instrumental values are the means by which we achieve the end goals. They can be based on competence (ambitious, intellectual, logical, responsible) or on morality (courageous, helpful, obedient, forgiving). Depending on which type of terminal and instrumental values we esteem more, we fall in a different part of the personal value quadrant.

For instance:

- Personal-competence: “I value wisdom (terminal), which I believe can be achieved through independent thinking (instrumental).”

- Personal-moral: “I value true friendship (terminal), which I believe can be achieved through honesty (instrumental).”

- Social-competence: “I value equality (terminal), which I believe can be achieved through ambitious work (instrumental).”

- Social-moral: “I value national security (terminal), which I believe can be achieved through obedience (instrumental).”

As you can see, the researchers did not attempt to define what are “good” or “bad” values. So, how should we go about assessing our personal values? In The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck, Mark Manson shares a practical framework. According to him, good values are evidence-based, constructive, and controllable, while bad values are emotion-based, destructive, and uncontrollable. This may seem obvious, but many of us hold values that are based on emotions rather than facts; that bring us unhappiness instead of personal growth; and that are largely out of our control.

According to Mark Manson, good, healthy values that are evidence-based, constructive, and controllable include intellectual curiosity, creativity, humility, honesty, vulnerability, standing up for others, standing up for oneself. Bad, unhealthy values that are emotion-based, destructive, and uncontrollable include feeling good all the time, being the center of attention, being liked by everybody, and being wealthy for the sake of being wealthy.

Discovering your personal values

There are several ways you can go about discovering your personal values. The first one is to identify people you admire, and to think about why you admire them. If you admire Marie Curie, is it because of her passion for learning, which made her passionately study on her own time while she was a governess? Is it because of her persistence in identifying a new chemical element, when other scientists were doubting her results? Is it because of her perseverance in conducting her work, even when her health started deteriorating because of the radioactive materials? A great way to perform this exercise is to write a short personal essay focusing on the values of the people you admire, and how they align with your own values.

The second strategy is simply to use a list of values, such as the one created by Dr. Russ Harris, the author of The Confidence Gap and an expert in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Take your time and choose your top six to eight values from the following list:

- Accomplishment

- Adventure

- Beauty

- Bravery

- Calm

- Compassion

- Connection and relationships

- Creativity

- Dependability

- Family

- Financial security

- Freedom

- Gratitude

- Health and fitness

- Leadership

- Learning

- Love

- Loyalty

- Nature

- Security

- Self-preservation

- Success

- Survival

- Work

- Other: ________________

- Other: ________________

Notice there is space for values that are not explicitly listed. Such a list only provides a starting point in exploring your values. In order to dig deeper and further refine your values, journaling can be a useful reflection method. Beyond a list of values, ask yourself: where did these values come from? Are there any alternative values that would better capture my internal beliefs? How can I better align my actions with my values?

The last question is particularly important. In order to be useful, values must be lived. Holding personal values but failing to use them to guide our actions amounts to the same as not holding these values at all. As Mark Manson puts it: “Our values are constantly reflected in the way we choose to behave. This is critically important—because we all have a few things that we think and say we value, but we never back them up with our actions. (…) Many of us state values we wish we had as a way to cover up the values we actually have. In this way, aspiration can often become another form of avoidance. Instead of facing who we really are, we lose ourselves in who we wish to become.”

Shaping your personal values

Your personal values do not have to be fixed. In fact, it is probably healthier for your values to change over the course of your life based on what you learn from your experiences and relationships with others. It is part of developing self-authorship. While this process often happens naturally, you can proactively decide to shape your personal values.

- Confront your values to actual experiences. Again, values do not exist in vacuum. Whenever you notice a contradiction between one of your values and your lived experience, take the time to reflect and consider whether your value actually reflects the way you want to behave in the world. If that’s not the case, it may be time to let go of that particular value, or to replace it with a new, better suited value.

- Develop self-awareness. Instead of coming up with rationalisations when feeling unhappy or disappointed, accept that sometimes our values are at fault. Let’s consider someone who spent a good amount of time trying to accumulate money, and realise being wealthy doesn’t bring them the happiness they expected. One reaction would be to think it’s because they don’t have enough money yet. A more self-aware reaction would be to realise money for the sake of money may not be the right value to live their life.

- Actively question your values. Finally, you don’t need to wait until experience contradicts your values, or until you feel disappointed in a value-led outcome in your life. You can actively question your values at a more abstract level. Especially in the case of values that were transmitted to you through your upbringing, education, or culture, it may be helpful to wonder: do I really want to live my life according to these values? Are there better values I should consider instead?

The goal is not to collect values to cling onto for the rest of your life. Instead, it is to live a life of self-discovery. It can be an uncomfortable process, but knowing who you are requires questioning your personal values.