Rationality and emotion may seem antithetic. One is objective, the other subjective. One relies on mental models, the other on gut feelings. When it comes to making decisions, we tend to favour the reassuring formal process of rationality over the impulse of our emotions. In school, we are taught how to think better, but rarely how to feel better.

However, it is foolish to think all of our decisions are purely rational. That is not to say taking emotions into account when making a decision is irrational: emotions are actually incredibly useful tools when yielded with care.

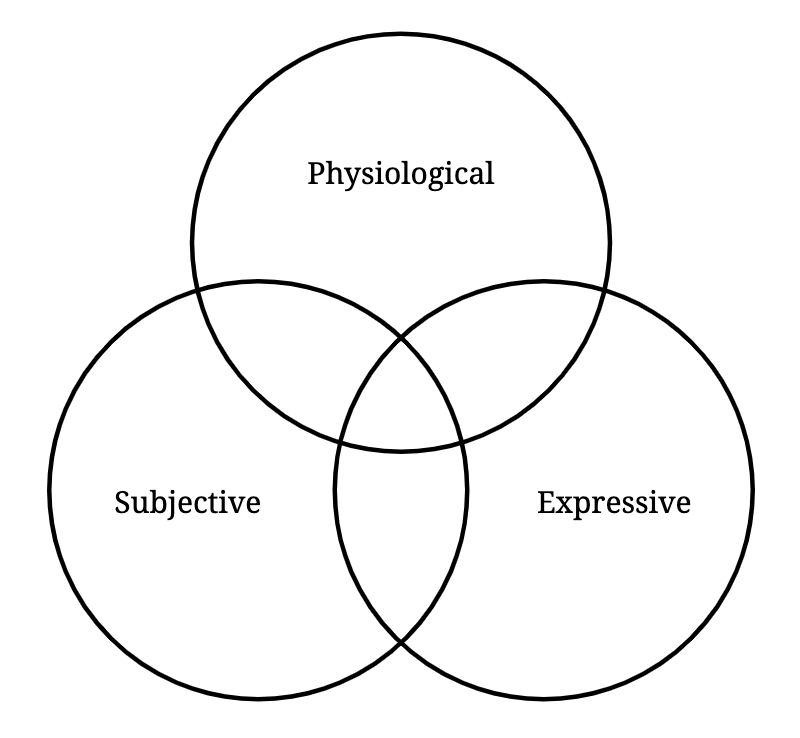

Emotions have three components which constitute your whole emotional experience:

- Physiological. How your body reacts to the emotional experience, such as changes in heart rate, blushing or turning pale, goosebumps, sweating, stomach cramps.

- Subjective. How you perceive the emotional experience, for instance funny, scary, sad, exciting.

- Expressive. How you react to the emotional experience, such as smiling, crying, laughing, shouting.

The interplay between these three components of emotions is extremely complex, but knowing that an emotion is not just one monolithic block you need to accept as a whole gives you lots of freedom to play with how you use emotions in your daily work and life.

A survival mechanism

First, it’s important to understand why emotions exist in the first place. Many emotions act as signals to the brain to take a specific action. Disgust is a good indicator you should not eat something, as it may be rotten or poisonous. If a food tastes nutritious, it’s probably full of calories and you should seek to find more. If you are in danger, fear activates your stress responses and tells you to flee.

The problem is that these “survival mode” emotions don’t make the distinction between perceived and real threats. The same stress response will be activated whether you are facing a lion hungry for a nice meal, or a crowd of conference attendees hungry for knowledge.

And because many of the threats we used to face barely exist anymore—for instance, you have a higher risk of dying from a stroke than killed by a lion, and a higher risk of being obese than to die of hunger—many of these automatic emotional responses are not appropriate anymore.

Most people are aware of the inadequacy of these automatic responses. As a result, many decide to try their hardest to suppress their emotions—or at least any kind of strong emotion. However, not only repressing your emotions is impossible, it is also harmful. Instead, emotions should be used as tools.

Emotions in social interactions

Emotions provide valuable information which allows us to better understand each other. Several surveys have found that most employers recognise empathy as a key to success. Being able to read someone’s emotional reaction and being able to control your own emotional reaction—the expressive component of emotions—is essential to interpersonal communication.

In The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, Charles Darwin was one of the first to study emotions as a communication tool. Hissing and spitting, for instance, would indicate angriness. While facial expressions of emotions are not culturally universal in humans, intra-cultural communication heavily relies on them.

Beyond facial expressions and body language, asking empathetic questions and listening to your interlocutor can offer more than cues as to how they feel. Being a good listener involves paying attention to your talk-to-listen ratio, paying attention to their words and their tone, and asking follow-up questions. All of these skills require emotional intelligence.

Emotions as a decision-making tool

Research suggests there are two main ways emotions affecting our decision-making:

1. Anticipated emotions. These are the expectations of how we will feel once gains or losses associated with our decision are experienced in the future. For instance, anticipating the excitement of working on an ambitious project may make you accept a new job. Anticipating the pain of getting sick in the future may push you to eat better. Anticipating the pride of finishing a marathon may motivate you to go for practice runs.

Anticipated emotions are a great tool to make decisions, but as all tools they need to be wielded carefully. Anticipating regret for not attending an event may lead to fear of missing out. Anticipating fear may prevent you from accepting a public speaking engagement. Being aware of our anticipated emotions is a first step in managing them for better decision-making.

2. Immediate emotions. These emotions are immediately experienced while we are deliberating and deciding. They are more vivid than anticipated emotions. For example, people who suffer from fear of flying don’t simply anticipate the fear they will experience when boarding a plane; instead, they immediately feel the fear of a plane crashing whenever they think about flying.

Immediate emotions can have a dramatic impact on the decisions we make. Feeling sad will make you more likely to sell an item for less. In a study, researchers found that “fearful people made pessimistic judgments of future events whereas angry people made optimistic judgements.” Other research suggests that frustration and anger will make you more likely to choose self-defeating options.

Being aware of how immediate and anticipated emotions work is crucial to rational decision-making. Immediate emotions should be managed so they don’t unconsciously interfere with the decision-making process. Anticipated emotions allow us to include our future self in the conversation, and can be used both as motivation tools and thinking tools.

Emotions have rational benefits such as helping us survive, communicate better, and make better decisions. Instead of trying to suppress them, we would all benefit from embracing these powerful tools and learning about them so we can use them wisely.