Mental models are shortcuts for reasoning. They are a set of ideas and beliefs that we consciously or unconsciously form based on our experiences to shape our representation of how the world works. While mental models are extremely useful to make decisions in times of uncertainty, they are still shortcuts—which can be harmful if we don’t take a step back to evaluate them.

Lucky for us, scientists have already devised a system we can take inspiration from. Evaluating the result of a chain of events and decisions is something that needs to be done every day in scientific research. In particular, scientists need to evaluate the validity and reliability of their measures.

Validity: is the mental model accurate?

In scientific research, validity is the extent to which a concept is accurately measured. To put it simply: are we measuring the right thing? As healthcare professionals Roberta Heale and Alison Twycross put it: “A survey designed to explore depression but which actually measures anxiety would not be considered valid.”

When it comes to mental models, questioning the validity of a mental model is equivalent to asking yourself: is this the right mental model for the situation? There are many mental models, and it may be that you apply the margin of safety mental model, when really you should be paying attention to your illusion of control.

Validity does not say anything about the mental model itself. Instead, it helps evaluate how appropriate and accurate a mental model is in a specific situation.

Reliability: is the mental model consistent?

Reliability is the consistency of a mental model when applied repeatedly under similar circumstances. Do you get the same result when you apply this mental model repeatedly?

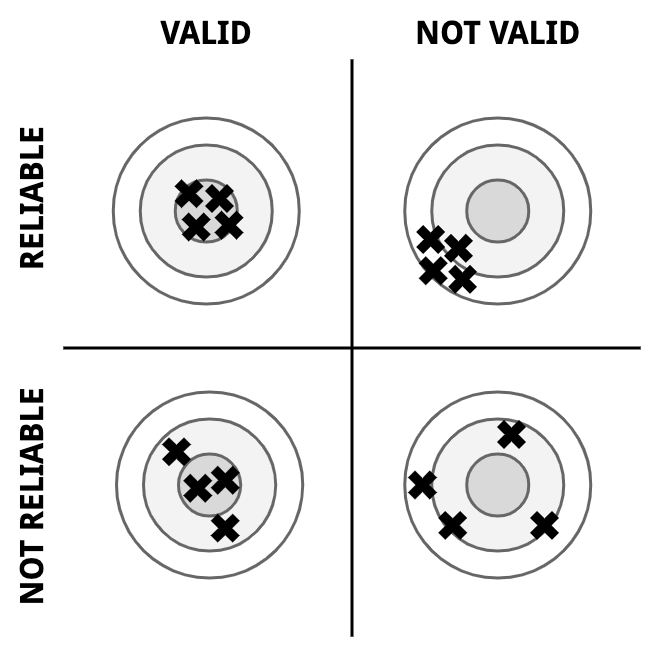

Roberta Heale and Alison Twycross share a good illustration to understand the relationship between validity and reliability: “A simple example of validity and reliability is an alarm clock that rings at 7:00 each morning, but is set for 6:30. It is very reliable (it consistently rings the same time each day), but is not valid (it is not ringing at the desired time).”

Scientists use several methods to evaluate the reliability of their measures, but two of them in particular are relevant to evaluating the reliability of mental models.

- The test-retest method. It consists in measuring the stability of a test over time. For mental models, you would need to keep track of the result of decisions made using a specific mental model. The more similar the results are over time, the more reliable the mental model. This is simple to achieve by adding a section to your daily notes or journal. Roam would be a great tool for this use case.

- The inter-observer method. In scientific research, this method looks at to what extent the measure yields the same result when administered by different observers under the same conditions. This is obviously much more difficult to achieve in real life, but it is interesting when it comes to mental models to discuss your experience with other people. Have they had the same results using the same mental model in similar situations?

Beyond reliability, maybe they used a different mental model which they consider more valid for that specific situation—and that’s worth discussing as well. After all, a mental model can be reliable but not valid (consistently returning a “bad” result), or valid but not reliable (inconsistently returning a “good” result).

As you can see, it would make little sense to consider validity and reliability separately. Why would you want to keep on accurately hitting the wrong target?

As often with metacognitive tools, the methods used in science to evaluate validity and reliability cannot simply be transposed to real life and the evaluation of mental models, but they offer a scaffold—a meta-model, if you wish—to guide your thinking.