Some people only help when it benefits themselves, others foster transactional relationships, while yet others are generous with their time and energy, without asking for anything in return. Whether in their personal or professional relationships, takers, givers, and matchers achieve different outcomes. Surprisingly, givers display the most radically distinctive results. Are you a taker, a giver, or a matcher? And how can you shift your reciprocity style to have a positive impact on your work, your relationships, and the world in general?

Takers, givers, matchers

In his book Give and Take, psychologist and Wharton’s top-rated professor Adam Grant divides people into three groups: takers, givers, and matchers. He explains: “Whereas takers strive to get as much as possible from others and matchers aim to trade evenly, givers are the rare breed of people who contribute to others without expecting anything in return.”

- Takers. Takers are self-focused and only help others strategically, when the benefits to themselves outweigh the personal costs. In the words of Adam Grant: “Takers have a distinctive signature: they like to get more than they give. They tilt reciprocity in their own favor, putting their own interests ahead of others’ needs.”

- Givers. On the other hand, givers will help whenever the benefits to others exceed the personal costs. As Adam Grant explains: “In the workplace, givers are a relatively rare breed. They tilt reciprocity in the other direction, preferring to give more than they get. Whereas takers tend to be self-focused, evaluating what other people can offer them, givers are other-focused, paying more attention to what other people need from them.”

- Matchers. Finally, matchers strive to preserve an equal balance between giving and getting. “Matchers operate on the principle of fairness: when they help others, they protect themselves by seeking reciprocity. If you’re a matcher, you believe in tit for tat, and your relationships are governed by even exchanges of favors.”

Of course, most people are not locked in one reciprocity style. “Giving, taking, and matching are three fundamental styles of social interaction, but the lines between them aren’t hard and fast. You might find that you shift from one reciprocity style to another as you travel across different work roles and relationships.” For instance, you may be a giver when mentoring a less-experienced colleague, act as a taker when negotiating your salary, and be a matcher when exchanging productivity tips with a friend.

Instead of an automatic behavior, choosing how we engage with friends and colleagues can be a conscious choice. Adam Grant explains: “Every time we interact with another person at work, we have a choice to make: do we try to claim as much value as we can, or contribute value without worrying about what we receive in return?”

The impact of giving

Does being a giver pay off? It seems giving does have a positive impact at an organizational level. Nathan P. Podsakoff and his team at the University of Arizona conducted a meta-analysis across 38 studies covering more than 3,500 business units, and found that companies with a culture of generosity and giving—which they call “Organizational Citizenship Behaviors”—are more likely to have higher productivity, efficiency, customer satisfaction, as well as reduced costs.

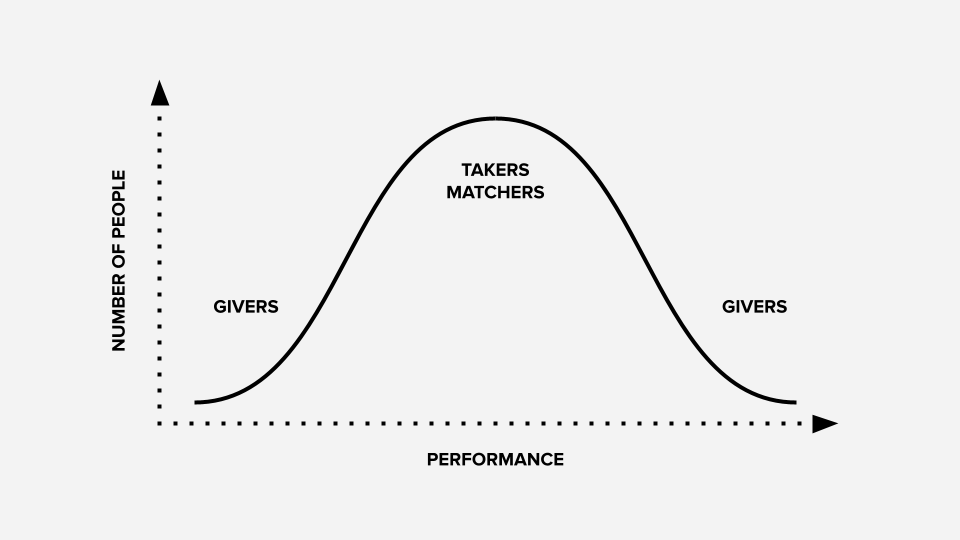

But you may want to ask about the individual impact of being a giver. The answer is pretty surprising. Givers are most likely to occupy both the lowest and highest levels of an organization. “The worst performers and the best performers are givers; takers and matchers are more likely to land in the middle. (…) Givers dominate the bottom and the top of the success ladder. Across occupations, if you examine the link between reciprocity styles and success, the givers are more likely to become champs—not only chumps.”

As you can see, givers are more rare than takers and matchers, and have dramatically different performance results. While low-performing givers say yes to everything at the expense of their own work, which has a negative impact on their time management, project delivery, communication, and execution in general, smart givers take into account what is best for the organization, not only what is best for the person asking for help. As a result, they are highly valued and manage to both be helpful to their colleagues while positively impacting their organization.

In addition, givers may get more support from fellow colleagues on their way up to success. “There’s something distinctive that happens when givers succeed: it spreads and cascades. When takers win, there’s usually someone else who loses. Research shows that people tend to envy successful takers and look for ways to knock them down a notch. In contrast, when givers (…) win, people are rooting for them and supporting them, rather than gunning for them. Givers succeed in a way that creates a ripple effect, enhancing the success of people around them.”

In essence, successful givers generate win-win-win situations, where they succeed, their colleagues are elevated, and the company performs better. Since givers can end up either at the lowest or the highest levels of performance, how can you make sure you are one of the most successful givers?

How to be a smart giver

If your goal is moderate success, you can decide to act like a taker or a matcher. But if you want to be part of the top performing members of your organization, or to have a positive impact on the world and foster win-win-win relationships with people around you, you may want to try to become a smart giver.

- Change your mindset. Consider the lens through which you are viewing your job and your relationships with friends and family. For your professional context, ask yourself who exactly is affected by your work? How do your choices impact the experience of colleagues and customers? How can you align your decisions so when you win, everyone wins? Instead of being self-focused like a taker or transactional like a matcher, think of an expanding pie where everyone can benefit from your success.

- Help wisely. A problem low-performance givers face is the lack of focus on the way they give. Tracking your impact does not mean you need to become a taker and only help when it benefits you, nor that you need to become a matcher and only help when you receive equal value in return. Rather, it means that you need to make sure you are helping achieve goals that are beneficial in general, not only to the person you are helping. Ask yourself: is this good for the company, for the customers, for the team? In a personal context, ask: is this good for our group of friends, our family, or our relationship in general? If the answer is no, try to brainstorm a better solution.

- Track your impact. From time to time, block some time for self-reflection to look back at past times you have helped, and what the outcome was. In the end, who benefitted from your help? Was it just one person, who may have been a taker? Or did your help have a wider positive impact, which justifies the time and energy you spent to provide your support? If you feel like your impact wasn’t as positive as you expected, try to think of the factors at play, and how you can be wiser next time you are asked for help so your involvement can be as beneficial as possible.

These strategies can be helpful for anyone, but especially for low-performing givers who are spending too much time and energy on providing scattered support which negatively impact their own work and relationships. Wherever you are on the spectrum of reciprocity styles, remember that it is a choice: you can practice wise generosity to become a smart giver and create a positive ripple effect around yourself.