Plato, Leonardo Da Vinci, Albert Einstein, Mary Shelley, Frida Kahlo… When we think about the most famous thinkers, inventors, and creators in history, we often picture one specific individual—a genius who uncovered something new where nobody was looking. However, this poetic vision of the innovator as a solo explorer doesn’t reflect the reality of humanity’s collaborative creative process: innovation is an emergent phenomenon better understood at the collective level.

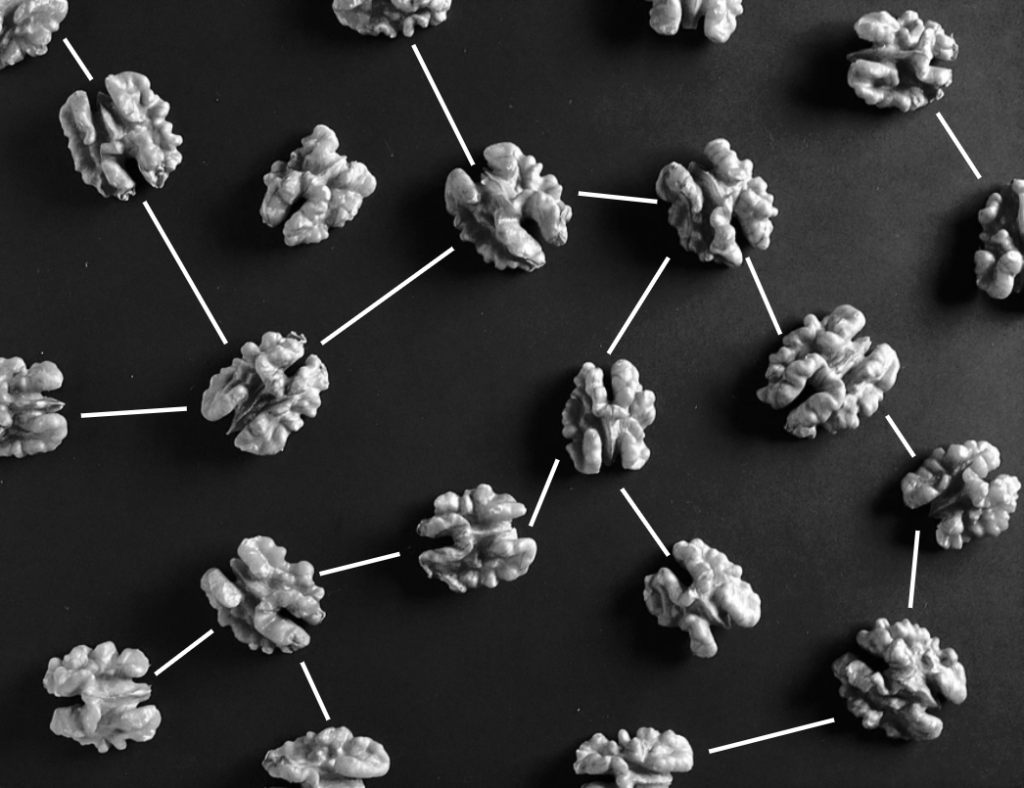

“Innovations, large or small, do not require heroic geniuses any more than your thoughts hinge on a particular neuron. Rather, just as thoughts are an emergent property of neurons firing in our neural networks, innovations arise as an emergent consequence of our species’ psychology applied within our societies and social networks.” — Michael Muthukrishna & Joseph Henrich.

Innovation doesn’t happen in isolation

In the 19th century, historian Thomas Carlyle popularised the concept of the heroic genius, which he called “the great man”—an individual whose cognitive abilities and creative potential far exceed the rest of the population, and who are the main source of innovation.

The human brain is incredibly complex and capable of wonderful feats. Yet, our minds have inherent processing and attentional limitations. But what our brains can’t achieve at an individual level is largely offset by what we manage to accomplish at a collective level.

In The Secret of Our Success, Joseph Henrich explains how having bigger brains means we need more energy, and how the need for that extra energy may be the root cause of our success as a species. See, there are only a couple of strategies a species could apply in order to compensate for a bigger brain: they could spend less energy (slow down their metabolic rate) or get more energy (acquire more nutritional resources). Homo Sapiens went for the latter.

Through better tools and better hunting techniques, we managed to gain access to higher calorie food sources. Then, through innovative food processing techniques—basically, cooking—we managed to unlock more calories from these food sources. All this adaptive knowledge was transmitted socially. Collaborating with fellow human beings was crucial to survival as an individual.

In essence, human evolution has been a key driver of innovation. A key difference between ourselves and less advanced species is our collective brain, a web of knowledge powered by an organic version of our modern networked thinking. Innovation does not happen in isolation. It happens within our collective brains.

The three components of innovation

There are many forms of collective brains, which differ in terms of size, interconnectivity, network properties, and regulations. Families, friendships, and institutions are all forms of collective brains. “Within these collective brains, the three main sources of innovation are serendipity, recombination and incremental improvement,” explain Dr Michael Muthukrishna, Associate Professor of Economic Psychology at London School of Economics, and Dr Joseph Henrich, professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University. Let’s have a look at these three sources of innovation.

- Serendipity. Research suggests that many innovations are actually unintentional—the result of mistakes or sheer luck. We have “stumbled upon” many of the things we know today. In Serendipity: Accidental Discoveries in Science, Royston Roberts lists many examples such as Penicillin, X-rays, Teflon, microwave ovens, Velcro, Post-It notes, artificial sweeteners, and more.

- Recombination. Combining different elements to come up with a new concept gives the appearance of individual genius, but it still relies on collective intelligence. Creativity is combinational in nature, which explains why many innovations emerged around the same time in history and in the same cultural context: inventors were exposed to the same ideas, and eventually recombined them to innovate. Some famous examples include the discovery of natural selection by both Wallace and Darwin; calculus by both Leibniz and Newton; oxygen by Lavoisier, Priestley, and Scheele.

- Incremental improvement. Gutenberg did not “invent” the printing press. Instead, he made (no less incredible) technological contributions to a process that already existed, which made the European book output rise from a few million to about one billion copies within a span of less than four centuries. Similarly, there were at least 22 inventors of incandescent light bulbs prior to Edison and Swan’s commercial success.

How do we go about creating an environment prone to innovation—where more serendipity, recombination, and incremental improvements can happen? The key seems to be to foster interconnectedness.

Interconnectedness and innovation

In an early model, Dr Henrich explained how more interconnected populations have more complex culture, and how such increases in sociality are associated with increased innovation. In his own words: “The first factor that affects the rate of innovation is sociality.”

For instance, research in Oceania suggests that both island interconnectedness and population size correlate with the tools’ number and complexity. Other researchers have found that urban density is a reliable predictor for innovation. “All else equal, a city with twice the employment density (jobs per square mile) of another city will exhibit a patent intensity (patents per capita) that is 20% higher,” they write.

The other two factors are transmission fidelity and transmission variance. Dr Heinrich defines transmission fidelity as “the fidelity with which individuals can copy different ideas, beliefs, values, techniques, mental models and practices.” Social tolerance, education systems, and access to knowledge and have an impact on transmission fidelity.

The other side of the coin is transmission variance, which is how much a copy differs from the original. While too much variance can result in costly mistakes, a few serendipitous mistakes can result in a useful innovation. Societies that tend to accept deviance, risk-taking and overconfidence—for example, societies where entrepreneurial pursuits are favourably perceived—often have higher transmission variance.

In short, increasing the rate of innovation can be achieved by fostering an environment with enough sociability (so we can collaborate and combine ideas), enough transmission fidelity (so we don’t keep on re-inventing the wheel), and enough transmission variance (so we can incrementally improve the wheel instead).

Instead of the heroic genius of isolated individuals, innovation emerges from the interconnectedness of our collective brain. Serendipitous discoveries, combinational creativity, and incremental improvements could not happen in a vacuum. By encouraging interconnectedness within our collective brain, we can increase the rate of innovation.

Muthukrishna, M., & Henrich, J. (2016). Innovation in the collective brain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 371(1690), 20150192.