Most advice about consistency sounds the same: try harder, be more disciplined, push through resistance. Discipline is often seen as the difference between people who succeed and people who don’t. And if you fall off, the explanation is usually moralized: not enough willpower, lack of grit, laziness.

But people don’t fail because they don’t try hard enough. They fail because the system they’re operating in makes sustained effort too costly.

From discipline to devotion

From a scientific perspective, discipline is the ability to apply self-control to override impulses in service of longer-term goals.

Decades of research suggest that self-control does predict positive outcomes. But it also shows something more subtle: self-control works best when it’s used sparingly. When people rely on constant “effortful inhibition” (forcing themselves to act) their performance degrades over time.

That’s because this kind of effortful inhibition activates brain networks that are metabolically expensive and sensitive to stress and fatigue.

Instead, research finds that people who appear highly disciplined are not constantly exerting more willpower. Rather, they tend to rely on habits, routines, rituals to maintain their wellbeing, and ways to design their environment that reduce the need for active control.

This is where devotion becomes a more useful tool than discipline. Etymologically, devotion comes from the Latin devovēre: to dedicate by a vow, to promise solemnly. Devotion implies commitment rooted in meaning and identity rather than forceful compliance with a rule.

When you’re devoted to an action, you don’t force yourself to act; the action expresses something you value.

Instead of effortful inihibition, this maps onto what researchers call “harmonious passion” – engagement that is freely chosen and integrated into your identity. Harmonious passion has been linked to greater persistence, better well-being, and being more likely to get in the flow.

How to design for devoted action

You’ve probably noticed that caring deeply about something doesn’t guarantee that you can act on it consistently. That’s because devotion doesn’t exist in a vacuum, and its impact depends heavily on friction – the total resistance between intention and action.

Friction can come from your environment, from a lack of skills or routines, or from the activation energy required to get started.

Two people can be equally devoted and have radically different outcomes because one is operating in a low-friction system and the other in a high-friction one.

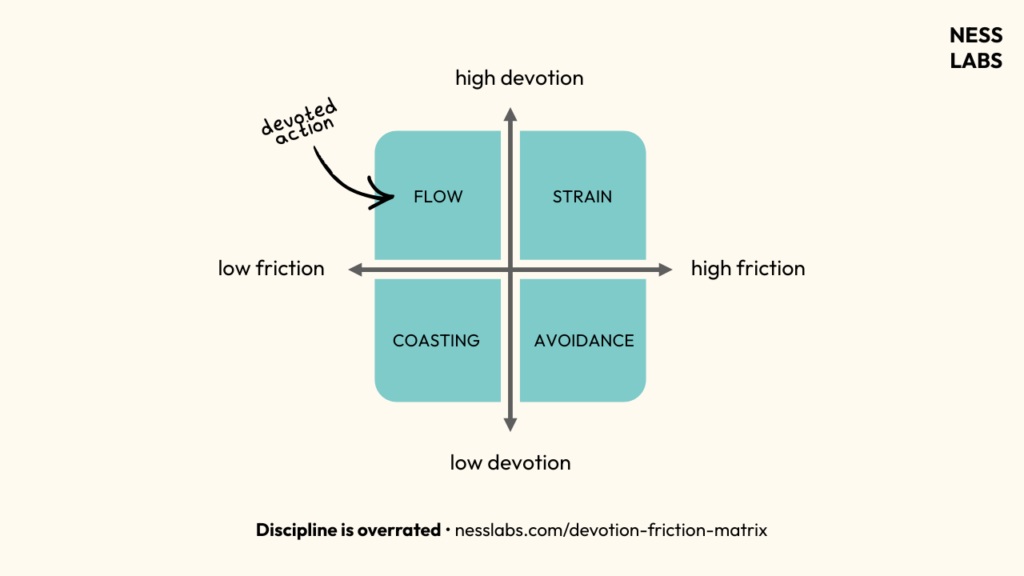

The Devotion-Friction Matrix of devoted action has four states:

- Flow (high devotion, low friction) where action feels natural and repeatable;

- Strain (high devotion, high friction) where caring is high but the cost of doing it is high too;

- Coasting (low devotion, low friction) where you keep going mostly because it’s easy;

- Avoidance (low devotion, high friction) where the task feels both unrewarding and hard to start, so it gets postponed or completely dropped.

There’s no point optimizing for maximal devotion or minimal friction in isolation. To get in the flow, you need to optimize for devoted action, where what you care about deeply is also easy enough to do repeatedly.

Here are three evidence-backed ways to do that:

1. Lower your activation energy. You might care a lot about working out or writing, but find yourself procrastinating. When that happens, stop focusing on finishing and focus on starting instead. For example, don’t say you’ll do a work out. Just put on your running shoes and step outside. Don’t say you’ll write the piece. Just open the document and write one sentence.

2. Design your environment. Make the desired action the default and the distractions slightly inconvenient. For instance, eave your book on your pillow and charge your phone in another room, or make unhealthy ones high-friction by putting them out of reach.

3. Run tiny experiments: Turn curiosity itself into an act of devotion. Pick one action to test for a specific duration, playing with variables such as timing, location or accountability, then observe what reduces effort and increases intrinsic reward.

If you want to show up reliably, don’t ask how to force yourself to work harder. Ask what you’re devoted to and what unnecessary friction is standing in the way. This way, consistency becomes a property of the system itself.