The human brain is a fascinating machine. The complex interactions in our mind shape our thoughts, memories, feelings and dreams, and ultimately make us who we are. Is there a limit to what this wonderful machine can accomplish? Is the human intellect capped to a certain level? If we project ourselves in, say, a thousand years, will we be able to learn and understand significantly more than we do today? Is there an inherent limit to what our brains can understand?

A powerful but limited machine

So you can imagine how powerful the brain is, let’s do a bit of maths. The human brain has about 100 billion neurons. While many popular publications report that each neuron fires about 200 times per second on average—and it’s the first number you’ll get if you look it up on Google—this number is most likely wrong. Scientists are not exactly sure what the number is, as different parts of the brain fire at different rates, but a paper suggests a rate of 0.29 per second, based on rough calculations. Each neuron is thought to be connected to about 7,000 other neurons, so every time a specific neuron fires a signal, 7,000 other neurons get that information. If you multiply these three numbers, you get 200,000,000,000,000 bits of information transmitted every second inside your brain. That’s 200 million million—a number too big to visualise. The point is: the brain is a powerful machine.

But, like every machine, it has its limitations. If understanding a concept was a recipe, you would need several ingredients: information, memory, and practice, which are all interlinked. The bad news is that the human brain makes us all inherently limited in our access to these. To gain information, we need to focus our attention on what we seek to learn—an ability that’s limited as we are terrible at multitasking. With limited attention comes limited input. Yes, there’s lots you could study out there—there is certainly no lack of information—but your capacity to attend to new information is capped.

Then, you need to encode that information into your memory. There are two major types of memory: short-term memory and long-term memory. Short-term memory includes working memory—the information you hold into your mind just for the time you need to use it. For example, remembering a phone number just long enough to type it, or an address just long enough to get there. Long-term memory, on the other hand, is a bit more complex. It includes autobiographical memory, which are life events you remember, explicit memory (also called declarative memory, your conscious knowledge of facts), and implicit memory, which you can tap into without any conscious thought, such as driving a car or writing something down.

Memory depends on forming new neural connections, and as we’ve seen before, we do have a limited number of such connections. When we age, it becomes harder for our brain to create new connections, and existing connections are being overloaded with several memories. It becomes both harder to learn, and harder to remember, as we tend to start confusing events and facts.

Finally, in order to effectively use information to form a deep understanding, you need to practice. Beside extremely important or sometimes traumatic events, the most effective way to form long-term memories is through practice. And again, because we don’t have unlimited time to practice everything we want to learn, there is a practical limit to our understanding of the world.

That being said, some human beings show an extraordinary ability to learn and remember information. For example, memory champion Chao Lu accomplished the feat of remembering 67,980 digits of pi in 24 hours. But that doesn’t mean we can infinitely expand the brain capacity. Instead, memory champions use techniques such as the method of loci (also known as mind palace), mnemonic linking (creating associations between the elements of a list), and chunking (breaking down and grouping individual pieces of information) to create new memories.

“Though every competitor has his own unique method of memorization for each event, all mnemonic techniques are essentially based on the concept of elaborative encoding, which holds that the more meaningful something is, the easier it is to remember” said Joshua Foer, a memory champion and journalist. Elaborative encoding is based on relating new information to previously existing memories. Research indeed found that long-term memories are made by creating meaning with the information we want to remember.

In theory, we could infinitely expand our knowledge by linking new bits of information to previous knowledge. But—of course, there’s a but—the issue here is that you need to have access to previous knowledge and to be able to give relevant meaning to the new information you’re trying to remember. You need to remember previous stuff to memorise new stuff; you need to understand new information with the help of previous memories in order to give it enough meaning to remember it. It’s like a snake biting its own tail.

Mind-expanding technology

We’ve established that the brain has attentional, multi-tasking and processing limitations. But there’s hope. Technology allows us to expand the capacity of our powerful but limited brains. We have started to use technology this way much earlier than you would expect. The very first time we decided to draw on the walls of a cave was the first time we used mind-expanding technology. Drawing was not only a way to communicate, it was a way to remember—to unload our memories onto a vessel much more durable and reliable than our brain. Every time you write down a quick note with pen and paper, you are using mind-expanding technology that multiplies the ability of your brain to remember information, assign it meaning, understand it, and make new connections.

Another amazing mind-expanding technology is mathematics. It allows us to represent concepts that we could not hold and visualise within our minds only. For example, no human being could hope to hold a mental image of all the complex processes that make up the climate system. That’s why we rely on mathematical models to do the heavy lifting.

We share the ability to count with many animals—studies found that certain monkeys can count the number of objects on a screen about 80% as well as college students could—but we wouldn’t be able to perform the mathematical feat of predicting the weather for up to ten days without computers. Nowadays, we not only unload much of our cognitive work on computers—just think about calculators, which add another level of abstraction to mathematics—but we actually stretch our thinking abilities thanks to computers.

In terms of expanding the mind’s ability to understand the world with a little help from technology, Tiago Forte has been advocating for building a second brain, a methodology for saving and systematically reminding of the ideas and insights we gained through our experience. The method consists in capturing information in a single, centralised place such as a note-taking app, connecting these pieces of information through linking and summarising, and creating tangible results in the real world. It’s a straightforward, effective approach that shares some common principles with my own mindframing method.

And there’s much more to come. Brain-computer interfaces such as neuralink promise to offer a true extension of the human mind by improving our memory, helping us learn, and ultimately making us smarter. Bi-directionality would mean we would have access to all the public knowledge in the world, at all times, with zero latency. We would go from simply looking up information using our mind, to just knowing facts as if we had actually spent time studying them.

Some researchers are exploring even more extraordinary means to expand the human mind. One of them includes connecting our brains to other brain cells, which could be placed in a Petri dish outside the body, or implanted in the belly. Such brain-brain interface would have a great impact on how we experience and understand the world.

“Constructed properly, this system could allow us to experience sensations and movements here fore only granted to other animals—perceiving in true infrared or ultraviolet rather than false-color extrapolations—and we could begin building an architecture to interface with abstract data forms, and indeed with other people, otherwise not possible in 2015. We could extend our nervous systems beyond being a puppeteer of individual vehicles toward being a conductor of swarms of robots, flocks of mechanical birds and fish to change shape and form at our will. Just as vision, sight and touch have their own dedicated neural pathways, we could create novel “search organs” to navigate the internet or large databases, to “feel” molecular structures or social network information,” explain the researchers.

Humanity is a supercomputer

In the meantime, we already have access to a supercomputer: humanity. Knowledge is not the products of a single brain. Knowledge is gained and shared by some, and then enriched by others. If there are current limits to what our brains can understand, there’s no reason to imagine a limit to what humanity can understand, especially now that we have the Internet to connect all our minds and share knowledge without any limitation.

The recent phenomenon of citizen science is a good illustration. It breaks down the walls of the laboratory and invites in everyone who wants to contribute. Citizen science ranges from crowdsourcing, where citizens act as sensors, to distributed intelligence, where citizens act as basic interpreters with a combined power that’s much more powerful than any existing computer. Participatory science allow citizens to contribute to problem definition and data collection, and actively involves citizens in scientific projects that generates new knowledge and understanding.

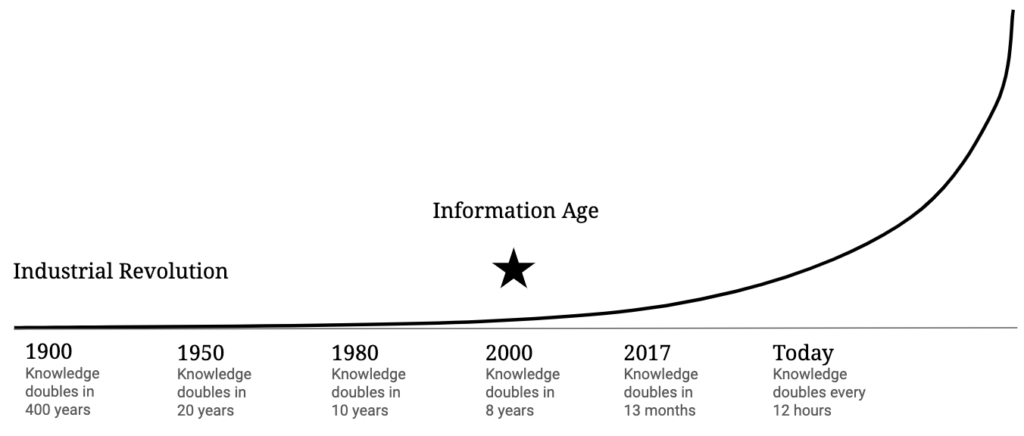

One human brain, with its inherent limitations, may not be able to understand everything about the world, but the collective power of humanity is slowly but surely bringing us closer to a theory of everything. The “Knowledge Doubling Curve” shows that until 1900 human knowledge doubled approximately every 400 years. By the end of World War II knowledge was doubling every 25 years. Today, human knowledge is thought to double every 12 hours. That’s a hell of a lot of knowledge when you look at it from a collective standpoint.

While innovation is often thought to be the work of a talented few, whose products are passed on to the masses, the not-so-secret to innovation is actually our collective brain. Researchers have argued that the three main sources of innovation are serendipity, recombination and incremental improvement. This is why languages with more speakers are more efficient to generate new knowledge and increase our understanding of the world—language affects the way knowledge can be shared and improved upon.

The bottom line? While we wait for ways to make our brains more efficient—either through the help of brain-computer interfaces or brain-brain interfaces or some other technology—you can already contribute to the collective brain of humanity by sharing your work and knowledge with others. With the Internet, the scale and impact your personal knowledge can have would have been impossible to fathom just a few years ago. And with human knowledge doubling at an exponential rate, only time will tell what kind of extraordinary understanding of the world humanity will have in the future.