Do you always find yourself excited by new ideas and projects? Being naturally curious, you enjoy learning, discovering new insights, and developing your skills. Your curiosity is one of your greatest strengths, driving you to explore and grow.

But that same curiosity can be a double-edged sword. With so many ideas competing for your attention, it can be hard to decide which one to pursue. You might experience choice paralysis, unable to commit to a single project because you don’t want to miss out on the others. As a result, you may find yourself starting many projects but only finishing a few.

This is what I call the “curiosity conflict”: the phenomenon where your greatest asset for creativity—your curiosity—can get in the way of your productivity. In short:

- High curiosity is what allows you to generate lots of creative ideas—it makes it easy to ideate.

- High curiosity is also what makes it difficult to focus on one idea—it can make it hard to execute.

The curiosity conflict can fuel a frustrating cycle that leaves you feeling stuck despite your wealth of ideas and your love for learning.

Curiosity’s Double-Edged Sword

Curiosity is connected to the brain’s reward system, which is heavily influenced by dopamine. When you encounter novel stimuli, your brain releases dopamine, which motivates you to learn more. This dopaminergic response is thought to be a key factor in the drive for exploration.

Research has shown that people with higher levels of curiosity tend to have greater activity in brain regions associated with reward processing. This heightened sensitivity to potential rewards may explain why highly curious people are more likely to engage in exploratory behavior and seek out new experiences.

But this same reward-seeking mechanism can also contribute to difficulty focusing on a single idea or project. When presented with multiple new ideas or projects, the curious brain may experience a surge of dopamine in response to each potential reward. This can create a sense of excitement and a desire to explore all the possibilities, making it challenging to commit to just one path.

In essence, the curiosity conflict arises from the brain’s struggle to shift from exploration to exploitation: the dopaminergic reward system that fuels curiosity can make it difficult to transition from the excitement of exploration to the more focused work of exploitation. How can you make that shift easier?

Resolving the Curiosity Conflict

The constant pull between the excitement of new ideas and the need to focus on one project is a natural part of the creative process. Fortunately, there are strategies you can use to navigate the curiosity conflict and make the most of your curious mind.

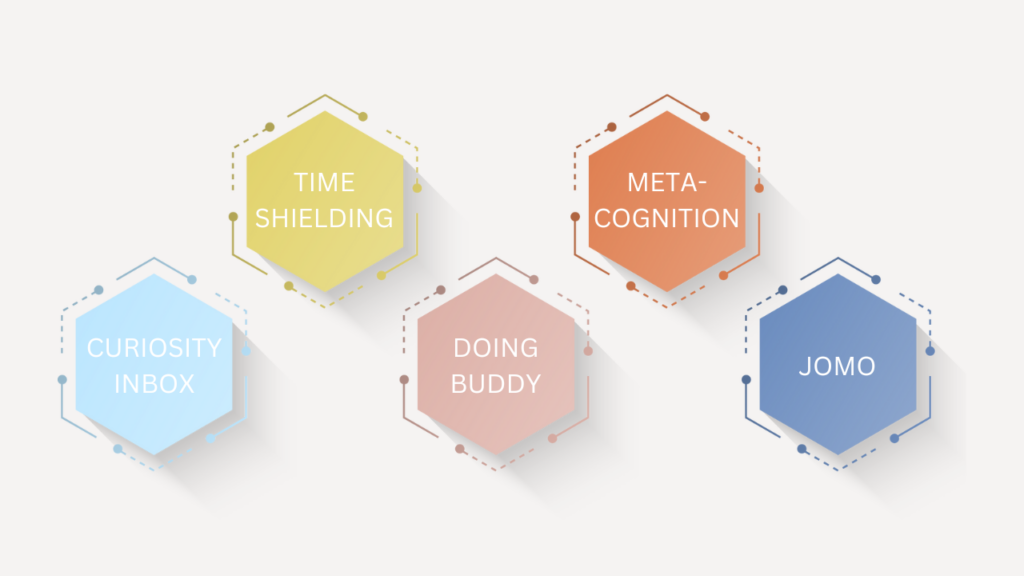

1. Keep a curiosity inbox. Whenever you get a new idea, write it down in a specific note or on a dedicated page in your notebook. Then, each time the idea pops back into your mind, give it a mark or increase its rating. Over time, you’ll develop a ranked list of ideas based on your long-term interests. This strategy allows you to continue exploring new ideas while also identifying which ones have the most potential for further development, which is a great way to manage your ideas without stifling your curiosity.

2. Shield time to shift from exploration to exploitation. Choose one idea from your curiosity inbox and spend an hour drafting an execution plan. Break down the idea into smaller, actionable steps and consider what resources you’ll need—time, money, support—to bring it to life. Feel free to use an AI companion to clarify your execution plan. By explicitly carving out time for envisioning the shift, you’ll make it easier to move from broad exploration to focused exploitation.

3. Partner with a Doing Buddy. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in the early days of Apple are a famous example of a thinking/doing duo. Jobs was the visionary thinker, while Wozniak was the engineering wizard who turned those ideas into reality. Similarly, identify someone in your network who has a knack for getting things done and partner with them to bring your idea to life.

4. Practice metacognition. Make sure to regularly reflect on your progress so you can balance exploration and exploitation. Think about ways you can focus your curiosity when executing on an idea. You can use the Plus Minus Next method to conduct a weekly review and assess what’s working, what could be better, and where you want to direct your efforts next. The “next” column will help you recognize when you’re getting pulled in too many directions and make a conscious choice to focus.

5. Embrace the joy of missing out. Your curiosity can make you more acutely aware of the potential benefits you’re foregoing by committing to one project over others. This heightened sensitivity to missed opportunities can fuel indecision and make it harder to focus on a single idea. But having many interests is a strength, not a weakness. Remind yourself that there will always be new ideas to explore. Trust that you’re not missing out by focusing on your current project.

Remember, the curiosity conflict is a natural part of the creative process. By implementing these strategies—keeping a curiosity inbox, shielding time to shift from exploration to exploitation, and finding a Doing Buddy—you can leverage your curiosity while also making tangible progress on your ideas, and you’ll feel better equipped to turn your ideas into reality.