Picture this: You’re at work with a big deadline coming up. Unfortunately, someone made a mistake, and part of the project needs to be completely redone in a rush. As the pressure mounts, you can feel the tension gripping your mind and body, causing your patience to wear thin.

In those stressful situations, it’s not uncommon to experience automatic negative responses that arise from the complex interplay between our thoughts and emotions. We may find ourselves snapping at a colleague or retreating into quiet as we try to cope with the crushing weight of anxiety.

So it’s not surprising that we tend to perceive stress as a negative phenomenon that should be minimized at all costs. In fact, a common misconception is that stress is inherently bad.

But stress is just your body and your mind’s response to external challenges. Depending on the particular stressors and your reaction, stress can be detrimental (distress) or beneficial (eustress).

The prefix -dis in “distress” has the same root as words like disconnect, dissatisfaction, and disingenuous. In contrast, “eustress” literally means “good stress.” It was coined by endocrinologist Hans Selye in 1975 to describe a positive cognitive response to stress.

Distress versus eustress

Distress can have a terrible impact on productivity, creativity, and mental health. On the other hand, eustress has been found to enhance performance and overall well-being, especially in the workplace. When you experience eustress, you’re pushed to do your best.

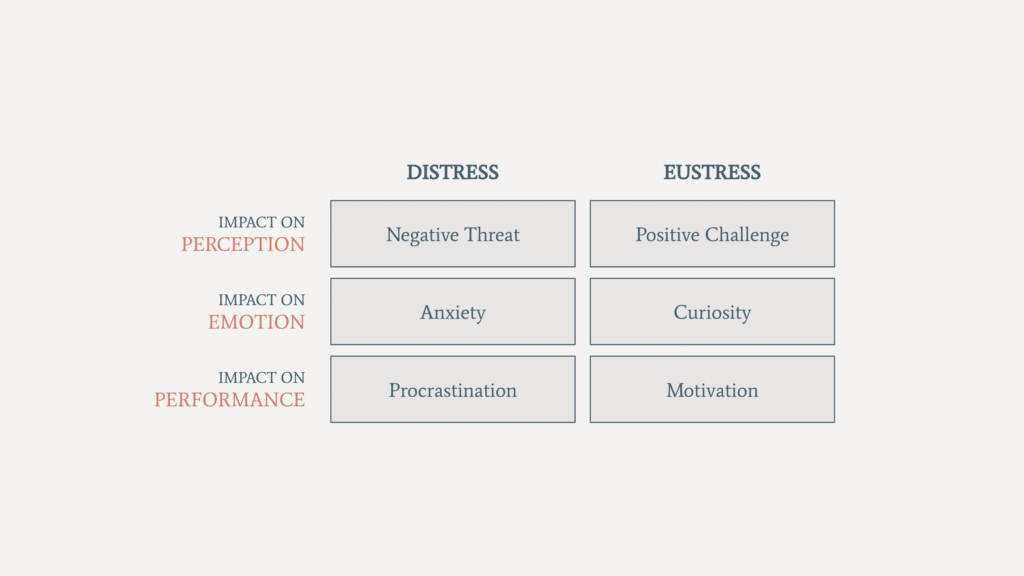

In short, distress results in anxiety; eustress is exciting. Distress leads to procrastination, while eustress is a source of motivation. Overall, distress has a negative impact on performance. On the other hand, eustress acts as a performance enhancer.

Here is an overview of the key differences between distress and eustress:

Experiences that lead to eustress are usually perceived as challenging but still within our coping abilities, leading to heightened focus and motivation. That delicate balance is where lies the secret to eustress.

A balancing game

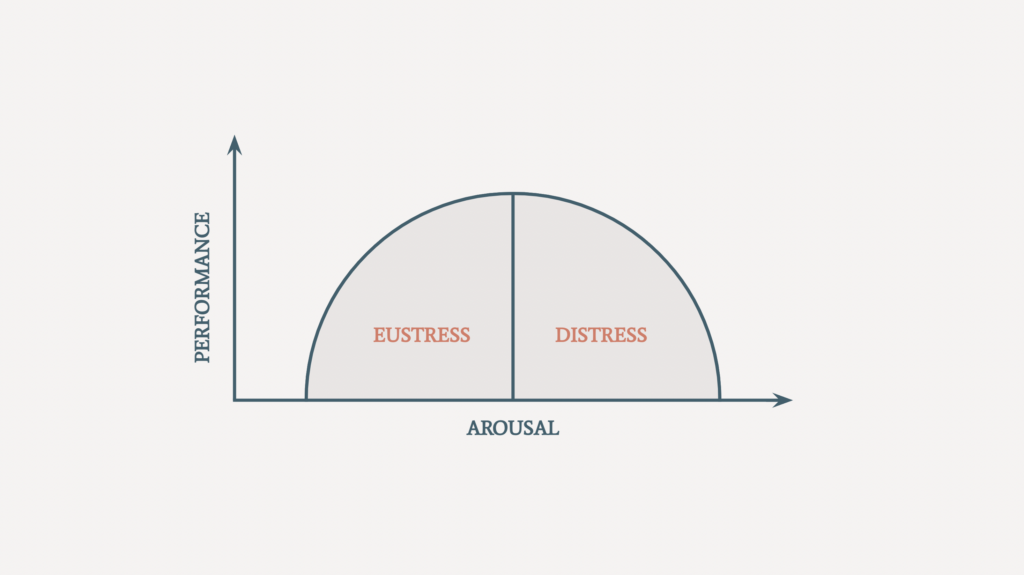

You need just the right amount of pressure to unlock the benefits of eustress. This is known as the Yerkes–Dodson law, originally developed by psychologists Robert M. Yerkes and John Dillingham Dodson in 1908, which states that performance increases with mental or physiological arousal—but only up to a limit.

But if you manage to strike that balance, eustress offers many benefits, especially for ambitious people who enjoy an interesting challenge. Some of the benefits of eustress include:

- Flow. Researchers described flow as the “ultimate eustress experience—the epitome of eustress.” When in flow, we are focused on the challenge and fully present. We become so fully absorbed in what we are doing, we lose track of time and can effortlessly ignore external distractions.

- Resilience. Because eustress is based on perception, cultivating eustress can help in reacting more positively to challenging situations, resulting in higher emotional agility. It can help us build better coping skills and boost confidence by reframing stressors as valuable learning opportunities.

- Self-efficacy. Your judgment of how you can carry out a required task or take on a specific role is a measure of your level of self-efficacy. Experiences of eustress allow you to accumulate evidence of your abilities and competence, and in turn, encourage you to explore more ambitious ideas.

The good news is: Though not all stress can be reframed as a positive experience, you can proactively manage many external stressors, so they result in productive eustress instead of paralyzing distress.

How to foster eustress

As eustress is a positive reaction to stress based on perception rather than objective stressors, the potential sources of eustress vary greatly between people. These are examples of stressors that are commonly perceived as positive:

- Learning a new skill. Working hard to learn something new is, for many, a safe source of eustress, creating the right amount of challenge while staying in control of the learning experience.

- Starting a new job. Because it’s a combination of using existing skills and learning new ones, while quickly forming relationships in a new environment, starting a new job can be challenging in the best ways, resulting in eustress. Similarly, receiving a promotion or moving teams can create good stress.

- Going on a holiday. Traveling to a distant place with a different culture can create eustress by forcing us to leave our comfort zone. Although travel can bring about distress—canceled flights, stolen items—many people view it as a fulfilling challenge.

- Starting a family. Whether getting married or having a child, starting a family can be a source of eustress by offering a novel challenge and many opportunities for personal growth.

- Moving. Finally, moving houses implies leaving the comfort of a familiar place behind to start a new life. The process is a source of negative stress for many people but can lead to eustress because of its inherently adventurous nature.

There are many other potential sources of eustress, such as playing competitive sports, some challenging video games, participating in a tournament, or having a complex but constructive debate with someone.

In order to find your own sources of eustress, the key is to experiment with positive stressors and to practice metacognitive strategies to reflect on their impact on your stress levels. A simple method to keep track of your stressors—whether they result in distress or eustress—is the Plus Minus Next method.

If you only remember one thing: Not all stress is bad and it can be a healthy source of motivation as long as you find your own positive stressors.