Stephen King didn’t become a bestselling author by reading about writing—he became one by writing every single day. The same applies to many successful people across various fields.

They didn’t just gather information—they took deliberate action, committing to daily practice that helped them refine their skills. Yet, so many of us continue to endlessly collect information while avoiding actual practice. Why?

In truth, most of us don’t suffer from a knowledge deficit—we suffer from a doing deficit. We take online courses and read books but rarely apply what we learn. The hard part isn’t learning what to do; it’s doing what we already know. So how can we shift from passive thinking to active doing?

Why We Resist Deliberate Practice

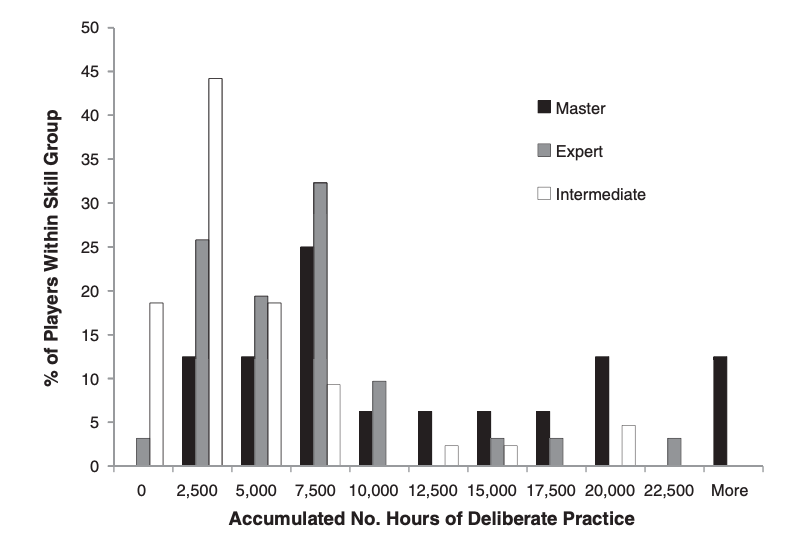

“Deliberate practice occurs when an individual intentionally repeats an activity in order to improve performance,” explains psychologist Guillermo Campitelli. Research shows that deliberate practice is necessary to master new skills, and that it takes about 3,000 hours of deliberate practice to reach an intermediate level of proficiency in a skill.

Deliberate practice isn’t just about putting in time; it’s about challenging yourself at the edge of your abilities. In addition, many skills are cumulative—you need to master the basics before moving onto more advanced topics.

However, understanding deliberate practice is one thing; actually doing it is another. Why is it so difficult to move from thinking to doing?

- Lack of immediate results. Deliberate practice can be slow and repetitive because you need to drill the same content over and over again in order to solidify the new connections in your brain. Although the fact that you’re struggling is actually a good sign, it can feel frustrating and make you want to quit.

- Discomfort with uncertainty. Deliberate practice involves venturing into the unknown. Unlike consuming content, which is relatively comfortable, practicing forces you to confront potential setbacks which you cannot predict.

- Fear of failure. When you start deliberately practicing, you will inevitably struggle and make mistakes. This can be demoralizing, leading you to retreat back into the safer territory of passive learning and thinking.

These challenges aren’t just theoretical—they’re deeply emotional in nature, and that’s why they often prevent us from committing to real, tangible practice even though we know at a rational level that we need to actually practice what we study.

Practice over Perfection

It’s easy to consume more information and convince ourselves that we’re making progress. But knowledge alone isn’t enough to build new skills. You need to take action. As Thomas Sterner, author of The Practicing Mind, puts it: “Progress is a natural result of staying focused on the process of doing anything.”

- Writing a book. In addition to reading about the best strategies from published authors to write a book, commit to writing one page every day.

- Learning a new language. Don’t just explore blog posts from polyglots; also sign up to a service that allows you to practice with a native speaker.

- Getting in shape. Once you’re done watching a few videos from fitness coaches to study the most effective routines, block time in your calendar to actually put these into practice.

- Learning how to code. Instead of just reading tutorials, commit to code something new every day.

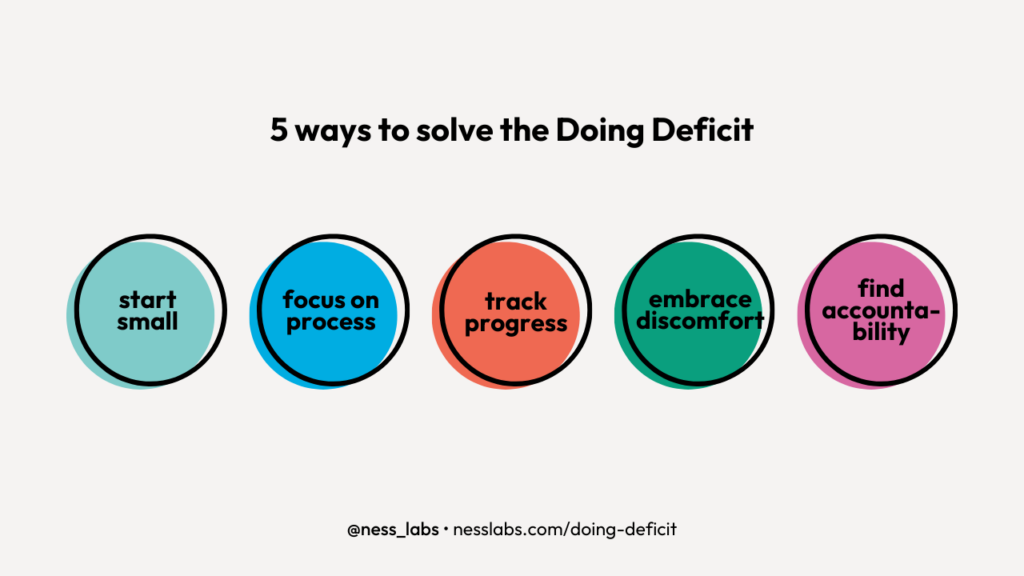

So how do you actually move from passive learning to active doing? Here are five practical strategies:

1. Start small. Choose one small action you can commit to. Rather than focusing on a huge task (like “write a novel”), narrow the scope of the action to something manageable, like “write 200 words a day.” The key is to make the commitment small enough that you won’t be tempted to skip it, but meaningful enough to build momentum.

2. Focus on the process. Don’t choose goals that are outcome-based like “become fluent in a language” or “get in shape.” Instead, direct your energy towards the process itself. The only goal is to show up consistently and to enjoy the journey. The reward is in the daily act of showing up, not in reaching a specific destination.

3. Track your progress. Just like a scientist, keep a journal of your practice sessions. Document what you did, how it felt, and what you learned. This will help you notice patterns and incremental improvements over time.

4. Embrace discomfort. Accept that mistakes are part of the process. When you feel resistance, lean into it—it’s a sign you’re pushing your limits. It’s often in those moments of discomfort that you’ll experience creative flow.

5. Find accountability. Tag team with someone who can help hold you accountable. Whether it’s a friend, a mentor, or an online community, having someone check in on your progress can help keep you on track even when things get hard.

Ultimately, solving the doing deficit is about answering this question: Are you willing to practice deliberately even when it’s uncomfortable? And, one step further: can you find satisfaction in the discomfort?

It requires welcoming failure and trusting that, over time, those small efforts will compound into meaningful progress. It means showing up every day, even when progress feels slow, and enjoying the slow process of mastering something new—finding joy is in the act of doing, not in reaching a specific destination.