When I was a kid, my parents struggled to understand why I always looked so tired. We had a curfew and were usually pretty quiet after bedtime. What was happening?

Well, I was reading. Sometimes until dawn. Treasure Island, The Lord of the Rings, His Dark Materials, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, The Count of Monte Cristo, Iliad, Odyssey, Les Misérables, Wuthering Heights, Madame Bovary. Everything Zola: Au Bonheur des Dames, L’Assommoir, Nana, Germinal, La Bête Humaine. And of course, Harry Potter. These books have shaped who I am today, and while I don’t read as much as I used to—I have since learned about the importance of sleep—reading is still an integral part of my life.

How to read a book is such a strange question. Is there really a specific way one should go about reading a book? Isn’t the act of reading good in and for itself? Thousands of people search for “how to read a book” every month, which got me curious. Someone even wrote a book about how to read a book, which is quite meta. That person is Mortimer J. Adler, and he had some interesting thoughts on the topic.

Why we read

The question of why we read is as old as the written world itself. Galileo saw reading as a mean to gain superpowers. Aldous Huxley thought of reading books as a way to make our life full, significant and interesting. “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies. The man who never reads lives only one,” wrote George R.R. Martin in A Dance with Dragons.

I ran a poll asking people why they read books. “To learn new stuff that helps shape my view of the world”; “Overwhelming curiosity”; “To challenge myself”; “To inhabit another’s mind”; “To think differently”; “To get inspired”; “It helps me keep sane, reading is kind of a meditative activity for me”; “It makes me smarter.” Interestingly, 45% of respondents said they read a mixture of both fiction and non-fiction books. Another 41% only read non-fiction books.

“Some books are to be tasted, others to be swallowed, and some few to be chewed and digested.”

Francis Bacon.

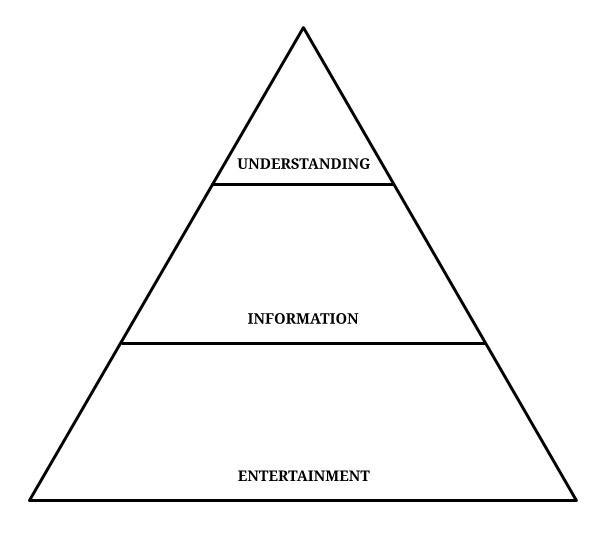

We read books for thousands of beautiful reasons. But, for the purpose of this guide, let’s distill these into three main categories.

- Entertainment. We sometimes read to relax, to escape, to dream. To hear an interesting story, to explore a new fictional world, to travel without leaving our couch.

- Information. We also often read to acquire facts about a place, a topic, or a person. Reading for informative purposes has a similar cognitive load to reading for entertainment. We don’t usually make a conscious effort to process the information.

- Understanding. Finally, we rarely read to develop new insights. Reading for understanding means actively shaping our vision of the world by questioning and analysing what we read.

When it comes to reading for entertainment, there really is no rule. As long as you enjoy the process, you should go for it. Don’t listen to people that say certain books are superior to others—it’s all about enjoying the moment. Fiction in particular should be savoured the way it tastes best to you. Whether you’re into epic novels, poetry, or comic books, who cares—the goal is to have a good time.

If you’re reading for information—such as reading the news, a biography, or a travel guide to organise a weekend trip—you could also argue there’s no need to overthink it. But it really depends on how much you want to gain from reading.

It’s especially important when it comes to non-fiction books. Do you want to read these in a passive way, or to make sure you gain deep insights and can form your own opinion? Most people are good readers when it comes to entertainment and information, but few have mastered the art of reading for understanding.

The four dimensions of reading

Adler’s main point in the first section of his work about how to read a book is that it’s best to gain knowledge straight from the source. Instead of going through a teacher sharing the main points of a book, he considered it better to read the book yourself. He called this concept “original communication”—the idea that information coming directly from those who first discovered an idea is the best way of gaining an understanding.

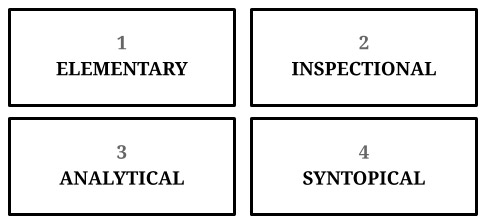

He then goes on outlining four main dimensions of reading, which are based on the goal we have when reading a book. For example, you may not have the same goal when reading Critique of Pure Reason versus, say, Fifty Shades of Grey. But it’s not only the material that matters, it’s our intention. And, according to Adler, very few people have the intention of understanding the material at a deeper level.

What does he mean exactly by understanding the material at a deeper level? Adler explains how these four dimensions of reading determine our understanding, how much we remember of what we read, and can progressively make us better active readers. Please note again these methods are best suited for non-fiction books. It would be a shame to read a good novel this way.

- Elementary reading. It’s the most rudimentary level of reading, referring to the reading level of a kid in elementary school. But even this level some people get wrong, for example by trying to use speed reading. “Every book should be read no more slowly than it deserves, and no more quickly than you can read it with satisfaction and comprehension,” Adler says.

- Inspectional reading. This step should happen before you give the book a proper read. The idea is to get the gist of the book before you decide whether or not it would be worth spending more time and get a deeper reading experience. We can do this in two ways. First, by using systematic skimming—having a look at the title, back cover, contents, and preface. This step should give you enough information to understand what the book is about and how it’s structured. Then, if you’re still interested, you can use superficial reading to get a feel for the big picture. You can take notes, but don’t stop to look things up. The goal is to get a view of the forest without getting lost in the trees. If after these two steps you still feel intrigued, move on to the next one.

- Analytical reading. Think of this step as the ultimate way to understand exactly what the author wants to communicate. Instead of a quick chat, you’re in for a long conversation. If you have taken notes in the previous phase, you can now expand on these. There are three aspects to analytical reading. First, the structural stage, where you analyse all the parts in the book—not limited to the table of contents. Outline these parts, their order and relation. Try to understand what question the author seeks to answer. Second, the interpretive stage, where you construct the author’s argument. Spot all the major keywords and distil the main propositions. What is being said? How? What’s the context? Lastly, in the critical stage, you will judge the soundness of the argument. It’s not about how much you liked or disliked the book—it’s about the merit of the premises, facts, and reasoning. By the end of the analytical reading phase, you will have a thorough understanding of the book.

- Syntopical reading. This is by far the hardest reading dimension of all four. It requires to read many books on a specific topic so you can compare their arguments. Once you have picked a research question, you will use the first reading dimensions to decide whether to use analytical reading or not for each book. You will also need to “bring the authors to terms”—to translate each author’s vocabulary into your own terms so comparison is possible across books. Syntopical reading is akin to drawing a map while exploring a new territory. It’s hard to not get lost but the journey itself is extremely rewarding.

If you want to give syntopical reading a try, a great place to start is the Syntopicon compiled by the very same Mortimer Adler who wrote the book about reading books. The Syntopicon is a collection of great ideas from western philosophy and their corresponding famous books. Some of the topics include democracy, liberty, emotion, habits, education, happiness, immortality, logic, and imagination. Writing an essay as you go is a great way to consolidate everything you learned through syntopical reading and share it with the world.

Understanding a book

How do you know when you’ve really understood a book? When you’ve gained deep knowledge rather than superficial information? Adler says you need to be able to answer four questions.

- What is the book about as a whole? This question is best answered by examining the front and back covers of the book and identifying its date, genre and general aims.

- What is being said in detail, and how? The first phase of analytical reading will help you answer that question. Look at the structure, understand the author’s argument. With many books, spending more time analysing the introduction and the conclusion is a good idea. This is where most authors get to the crux of their argument.

- Is the book true, in whole or part? The second phase of analytical reading is about questioning the argument—constructive criticism. Are the premises, facts, and reasoning sound? Are there any holes in the argument?

- What of it? This last question requires comparing the book with other resources dealing with the same topic. It’s about connecting the dots and forming your own informed opinion. Adler and Van Doren to imagine being seated at a large table beside the authors you have read and joining the conversation.

Another way to gain a deep understanding of a topic through reading is to create a mind-map connecting concepts and arguments across many different authors. If you’re really nerdy, you can even do this with novels. For instance, someone created a detailed map of all the connections between the Lord of the Rings’ characters—aptly called “One Graph To Rule Them All”. While nobody should feel forced to go to such lengths when enjoying a fiction book, we can’t argue this person has gained a deep understanding of the Lord of the Rings.

As Abraham Lincoln said, “a capacity and taste for reading gives access to whatever has already been discovered by others.” Reading a book is a way to temporarily walk into someone else’s shoes. How much you want to understand the way they think and see the world is up to you.