When being able to do everything prevents you from achieving anything

This morning, I sat in front of my laptop and asked myself a simple question: what should I work on today?

Looking at my projects in progress, I have three literature reviews I find interesting, an app idea that could be useful for the Ness Labs community, and a dashboard I’ve started building for my team.

With AI tools like Claude Cowork and OpenClaw, each one feels only a few prompts away from a solid first draft: research outlines appear instantly, interfaces prototype themselves, and code that once required weeks is now written in minutes.

Technically, I can do almost anything. Practically, I’ve noticed a worrying shift: I keep starting new things and finishing very few. It feels like being surrounded by infinite drafts.

What should you work on when everything is technically possible? This question is what I call the Omnipotence Dilemma.

Power without progress

We’ve reached a point where, for the first time in humanity’s history, virtually anyone can work on anything. You have a team of infatigable skilled workers ready to do research, build apps, send emails, and answer all your questions along the way.

We tend to think more capability automatically leads to more progress, so that sounds great in theory. But what I’m noticing is that when the cost of taking action approaches zero, a strange dynamic seems to appear.

First, when starting something no longer requires much sacrifice, it stops functioning as a decision. You don’t choose one path instead of another – you can begin several at once, and nothing forces prioritization anymore. You can rapidly prototype ten versions of something without ever deciding what it is actually for.

And when a draft, plan, or prototype can be generated instantly, creation starts to feel like selection rather than authorship. This is the rise of what’s been called autocomplete culture: instead of wrestling with an idea, you refine options already proposed to you. Yes, you can generate anything, yet less of it feels fully yours.

Limited time, skills, and resources once forced us to choose, and those choices accumulated into a direction. In my first year as a neuroscience student, I also took web development classes. I loved them, and I’m still glad I learned the basics which are useful to me every day. But after a few months, I had to decide where most of my time and attention would go.

This didn’t mean choosing just one thing (impossible for a hypercurious mind!), but it did mean prioritizing. I decided that I’d spend ~60% of my time on neuroscience, 20% on writing, and the remaining time on learning other skills (including webdev) as needed. And in that way, scarcity helped shape my identity. Today, that sense of scarcity is gone.

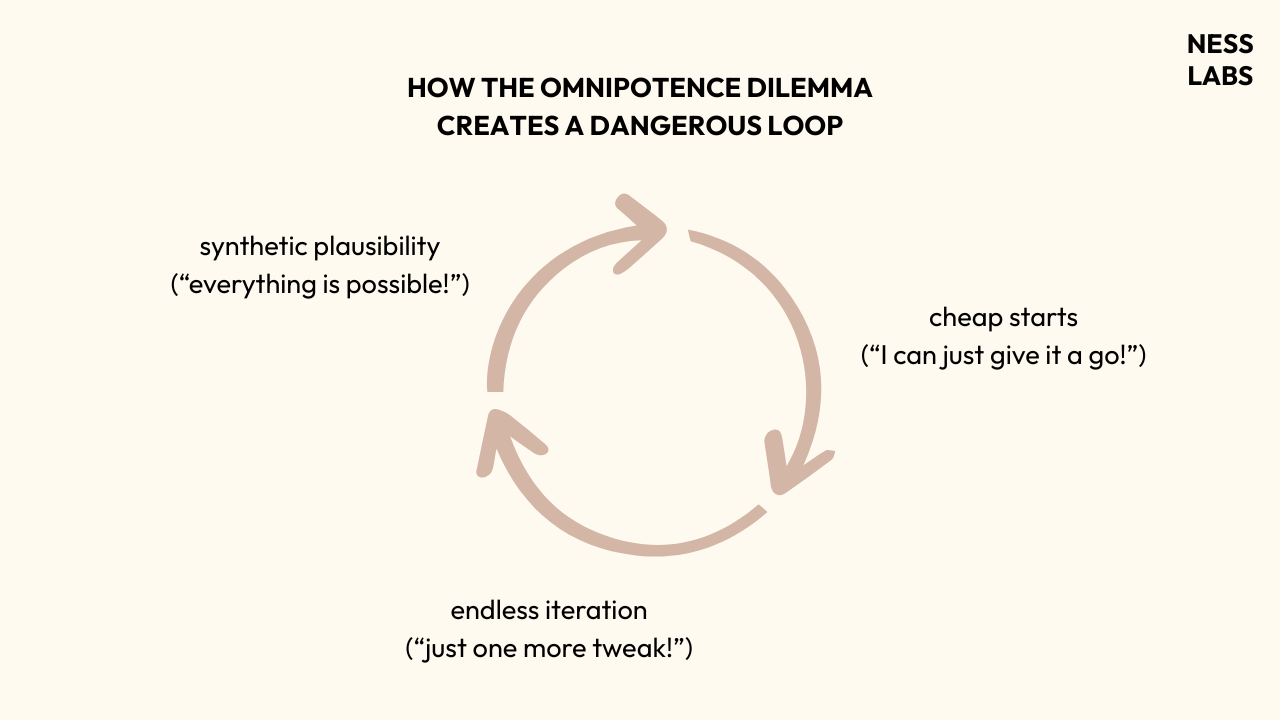

Taken together, these dynamics form a dangerous loop:

1. Synthetic plausibility. AI can construct convincing plans for nearly anything. When almost every idea sounds viable and every path appears reasonable, prioritization becomes harder.

2. Cheap starts. Beginning something used to require at least some commitment, even if just in the form of time investment. But starting has become effortless – just one prompt and you’re on your way – and the stakes are so low that it’s almost a form of consumption.

3. Endless iteration. Projects are endlessly refined, abandoned or replaced, creating the sensation of progress even when nothing meaningful moves forward.

The deeper cost is that you outsource the hardest but most important part of creative work: forming a view. What becomes scarce is no longer skill or access. What becomes scarce is attention, conviction, taste, trust, time, and responsibility.

And what worries me the most is that this cost shows up slowly. Projects that don’t quite make sense. A subtle loss of our ability for strategic thinking and meaning-making. Being unable to articulate why in the first place you’re doing this work.

Sandboxing your curiosity

Instead of thinking like a maximizer trying to pursue every promising direction, it helps to think like a scientist running experiments.

An experiment has a clear scope. It has a duration. It produces learning whether it succeeds or fails.

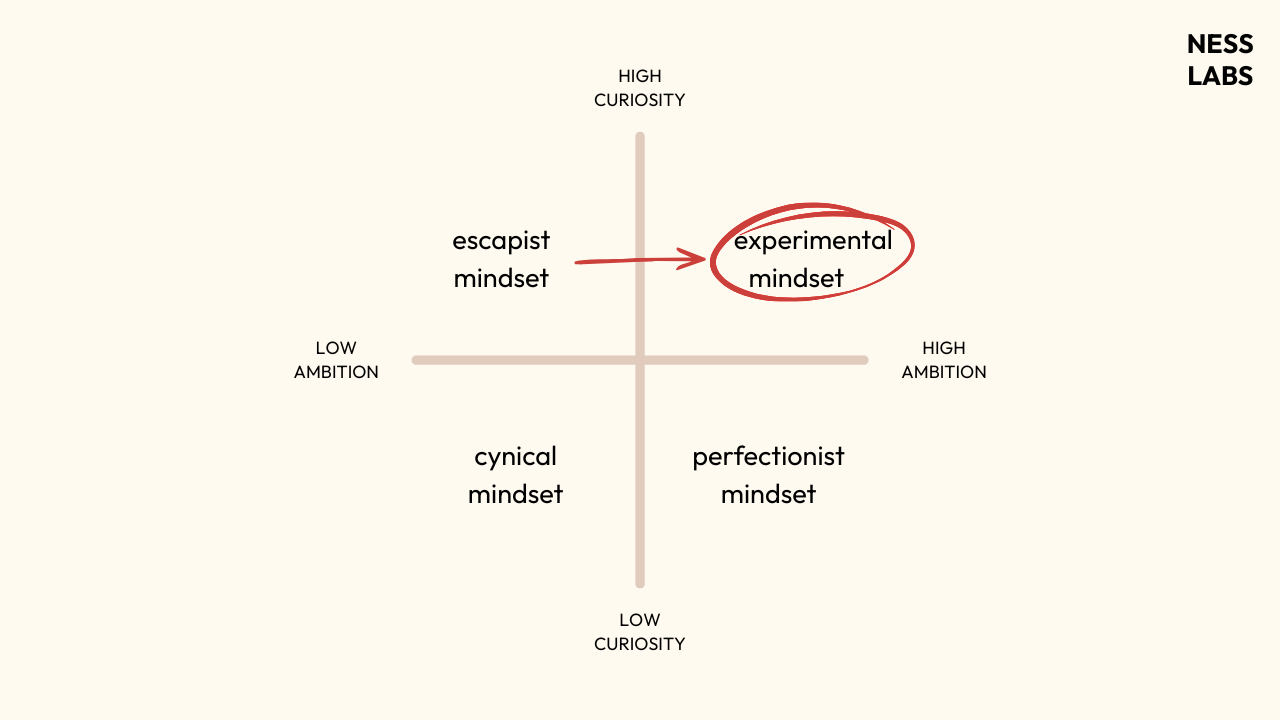

It allows you to shift from an escapist mindset to an experimental mindset by choosing projects at the intersection of curiosity and ambition – work that genuinely interests you while also stretching your capabilities and contributing something meaningful.

Then, to apply that experimental mindset, turn your area of curiosity into a mini-protocol using this format:

I will [action] for [duration].

Whether that’s a two-week prototype, a month of writing, ten published essays around a topic you truly care about, this kind of tiny experiment provides a clear sandbox for you to explore and actually learn and grow.

At the end of your experiment, take time to reflect. What worked? What didn’t? Based on what you learned, what would you like to experiment with next? This allows you to replace the dangerous AI slop loop I described earlier with a metacognitive loop, where each iteration is an opportunity for self-discovery.

In an age of near-omnipotence, curiosity has never been easier to satisfy. And yet, meaningful progress still requires committing to your curiosity – not by pursuing everything at once, but by choosing an interesting path to explore deeply enough for something meaningful to emerge.