When you think about people conducting experiments at home, you might picture scenes from old horror movies – a wild-haired scientist in a dark basement, mysterious bubbling potions, and mad declarations along the lines of “It’s alive!”

Fortunately, the reality of personal science isn’t so dramatic. It can be as simple as a few careful observations about our own lives: noticing how different foods affect our energy, tracking what helps us sleep better, or documenting changes in our mood.

This kind of self-study has been around for as long as humans have been curious about how their minds and bodies work. Let’s explore the origins of personal science and how you can practice it in your daily life and work.

Personal science through the ages

Throughout history, humans have studied themselves to understand how their bodies and minds work. Ancient healers documented the effects of different remedies. Philosophers kept detailed records of their thoughts.

These weren’t just random observations – they were early examples of self-experimentation. One of the most remarkable examples comes from the psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus. In the 1880s, he conducted extensive memory experiments on himself, methodically testing how quickly he learned and forgot nonsense syllables. His findings about memory and learning are still relevant today.

The term “personal science” itself is relatively new. Psychologist Seth Roberts defined it as “using science to solve your own problems.” When the concept first appeared in academic literature in 2016, researchers described it as “an interest in collecting data about their own bodies or lives in order to obtain insights into their everyday health or performance.”

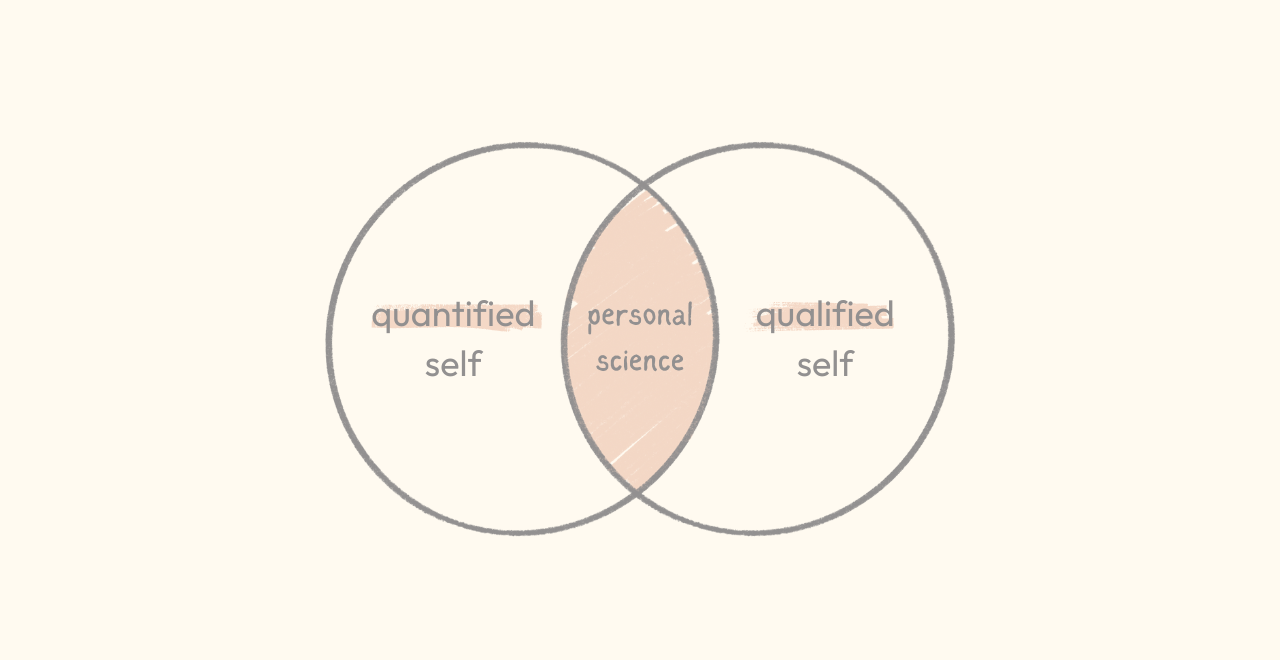

Technology has transformed how we study ourselves. What started as the quantified self movement – a small group of enthusiasts using technology to track their activities – has become mainstream. Today, millions of people use smartphone apps and wearables to monitor everything from steps to sleep patterns.

But while these tools are useful, they’re just one part of a much bigger picture. Personal science isn’t just about collecting numbers – it’s about understanding our individual experiences and making meaningful improvements to our lives.

Beyond the quantified self

The rise of fitness trackers and health apps has made personal data collection easier than ever. But this focus on numbers and metrics can obscure that not everything that matters can be measured, and not everything we measure matters.

As sociologist Jenny Davis notes, “self-quantifiers don’t just use data to learn about themselves, but rather, use data to construct the stories that they tell themselves about themselves.”

That’s why the qualified self is as important as the quantified self. Whether it’s an athlete documenting how different warm-up routines affect their performance, or a salesperson tracking their energy levels throughout the day… Some of the most valuable self-knowledge comes from qualitative observation.

And long before digital tracking became popular, people were documenting their lives in rich, qualitative ways. They would record detailed observations about their daily experiences, relationships, and inner lives.

Personal science done well combines both measurement and meaning-making: when we track aspects of our lives across several dimensions, we can make sense of how we live. Our personal records become tools for self-discovery.

This is what sociologist Deborah Lupton calls the “reflexive monitoring self” – a practice where we continuously observe and reflect on our experiences, creating a feedback loop to develop a deeper awareness of our patterns, whether it’s habits or responses to different situations. This reflexive process helps us make more informed decisions about our work, health, and relationships.

Tools for personal science

The beauty of personal science is that you don’t need expensive equipment or complex protocols to get started. Here are some effective tools that anyone can use:

- Journaling. The simplest and most versatile tool for personal science is a notebook. Whether paper or digital, regular journaling helps you spot patterns and connections you might otherwise miss. The key is consistency – even brief daily notes can build into valuable insights over time.

- Digital tracking. Apps and wearables have made data collection almost effortless. They’re particularly useful for things that are hard to track manually, like sleep patterns or heart rate variability. But remember to focus on metrics that actually matter to you rather than tracking everything just because you can.

- Tiny experiments. You could try a new morning routine for two weeks while keeping other variables constant, or test different work environments to find what helps you focus best. Document both what you did and how it affected you throughout the experiment.

- Weekly review. Set aside time each week to reflect on your observations and experiments. Ask yourself: What worked and what didn’t? What patterns am I noticing? What experiments should I try next?

- Curiosity circle. Meet regularly with other experimentalists to discuss the ways you are capturing your observations, reviewing the data, and testing different assumptions in your personal and professional lives. Learn from each other to improve your approach to personal science.

Personal science isn’t about creating monsters or magical potions. It’s about systematic curiosity and the desire to understand ourselves better. We’re all scientists of our own lives, conducting the most important experiments of all: discovering what helps us live better, healthier, and more fulfilling lives.