We all know that one chain-smoker who lived an old, healthy life. We read everyday about Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg—college dropouts who started billion-dollar companies. And we tend to attribute our own success to dedication rather than luck. These are all typical examples of survivorship bias.

Survivorship bias is a common bias that leads to false conclusions by focusing on the elements that made it past a selection process, and overlooking the ones that did not. We see the ones who “survived” and pay no attention to the ones who failed.

Nobody would have written a long article on one of the many, many chain-smokers who die from cancer. However, every publication was eager to cover the story of Batuli Lamichhane, a woman who at the time was 112 years old and smoked 30 cigarettes a day. She celebrated her 118th birthday in March 2020, making her one of the oldest living persons in the world. Quite the story, huh?

In the case of Batuli Lamichhane, we know enough about the toxicity of cigarettes to realise this is a lucky fluke, but many smokers will still hope they are part of these lucky few who somehow are not affected by their smoking habit. And that’s not all. Beside this extreme example, we fall prey to the survivorship bias on a daily basis.

The survivorship bias is ubiquitous

None of the countless entrepreneurs who dropped out of college to launch a startup and failed ended up on the cover of Forbes. Companies that don’t exist anymore are not included in historical market performance reviews. When trying to predict the future from the past, the survivorship bias is an ubiquitous experimental flaw.

This tongue-in-cheek tweet prompted me to write an article about survivorship bias:

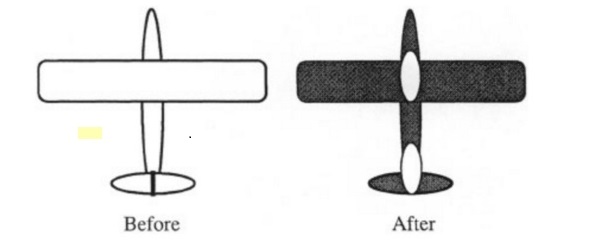

One of the most famous examples of survivorship bias happened during World War II. The U.S. military was trying to reduce aircraft casualties. In order to figure out which parts of the aircrafts were most vulnerable, they analysed the patterns of the bullet holes from planes returning from conflict. The results were clear: the wings and the tails were receiving the most bullets. Thus, the conclusion was to increase armour in these areas.

A statistician called Abraham Wald stepped in and suggested an entirely different conclusion: the U.S. military should increase the armour around the engine of the aircrafts, he said. The planes that come back are the ones that got hit in the wings and tail. The ones that got hit elsewhere—the engine—didn’t get back and therefore were not included in the U.S. military’s analyses. In The Black Swan, financial statistician and author Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls this data clouded by survivorship bias the “silent evidence”.

The issue of survivorship bias is also evident in business. As Daniel Kahneman puts it in Thinking, Fast and Slow: “A stupid decision that works out well becomes a brilliant decision in hindsight.”

Most entrepreneurs—if not all—don’t know what they’re doing. They don’t have a meticulous step-by-step plan to follow. Yet, we tend to try to emulate the “recipe” used by the few ones that achieved success.

In most cases, these successful entrepreneurs will create an after-the-fact narrative to explain how their vision turned into reality, omitting to admit the part luck and circumstances played in their success. And, because of the survivorship bias and our love for good stories, we tend to believe them.

How to avoid the survivorship bias

While optimism can actually be helpful, inflating our likelihood of success because we forget to include failures in our dataset will add unnecessary risk to an already complex decision-making process. There are three strategies you can apply to avoid the survivorship bias:

- Look for what’s missing. We tend to focus on the visible. Instead, pay attention to the invisible. Whether looking at successful entrepreneurs, bullets in aircrafts, or chain-smokers, go past the obvious winners: consider all the elements that did not make it past the selection process.

- Accept the role of luck. Whether you or someone else becomes successful, try to not fall in the trap of attributing your success to skills and hard work only. However hard someone worked, there is very likely there was an element of luck—whether meeting the right person at the right time, receiving unexpected support, or stumbling upon a valuable piece of information.

- Beware of retrospective recipes. When people ask: “How did you do it? What made you successful?” it’s tempting to answer with a detailed step-by-step plan, but it’s rarely a reflection of reality. Share your mistakes, your failures, as well as your breakthrough, but do not present these as more than your personal journey, and encourage people to figure out their own recipe. Similarly, be cautious with overly prescriptive content claiming to know the exact correct steps to success.

It feels reassuring to think we can just reproduce whatever a tiny percentage of successful people did. But if it worked this way, we wouldn’t have so few highly successful artists, scientists, writers, designers, and entrepreneurs. Instead of trying to apply a “tried-and-tested” recipe for success based on a non-representative sample, a better use of our time would be to define what success means to us.