Taking smart notes is one of the most efficient ways to increase your productivity and your creativity. But what kind of notes? Once you start considering all the mediums, techniques, strategies, and formats available to you when taking notes, the combinations are almost infinite.

This attempt at a taxonomy of notes was inspired by a conversation between software engineer Andy Matuschak and Conor White-Sullivan, founder of Roam Research. Andy published his own taxonomy of note types, which includes “ephemeral scratchings”, “prompts and incomplete notes”, as well as evergreen notes. In response, Matt Brockwell shared his four levels of evergreen notes and Alex Chamessian a taxonomy based on aims, types, and sources of notes.

The exercise is not new. In a 1962 book about study methods, Edgar Wright and Jean Wallword proposed a first taxonomy of notes based on the source of the note, separating “note-taking” from “note-making.” They argued that note-taking happened while listening, and note-making while reading. According to them, note-making is a more relaxed process, as one can take their time to abbreviate the facts and ideas they read.

In 2015, Professor Alaa M. Al-Musalli published a paper detailing the taxonomy of skills necessary to note-taking. Beyond accurate analysis, rapid writing, and the ability to easily read back, there included literal skills, inferential skills, critical skills, and creative skills.

To my knowledge, there is no taxonomy consolidating all of these approaches. Here is an attempt at solidifying these classification methods. In theory, you should be able to describe any kind of note by selecting its corresponding class within each taxon.

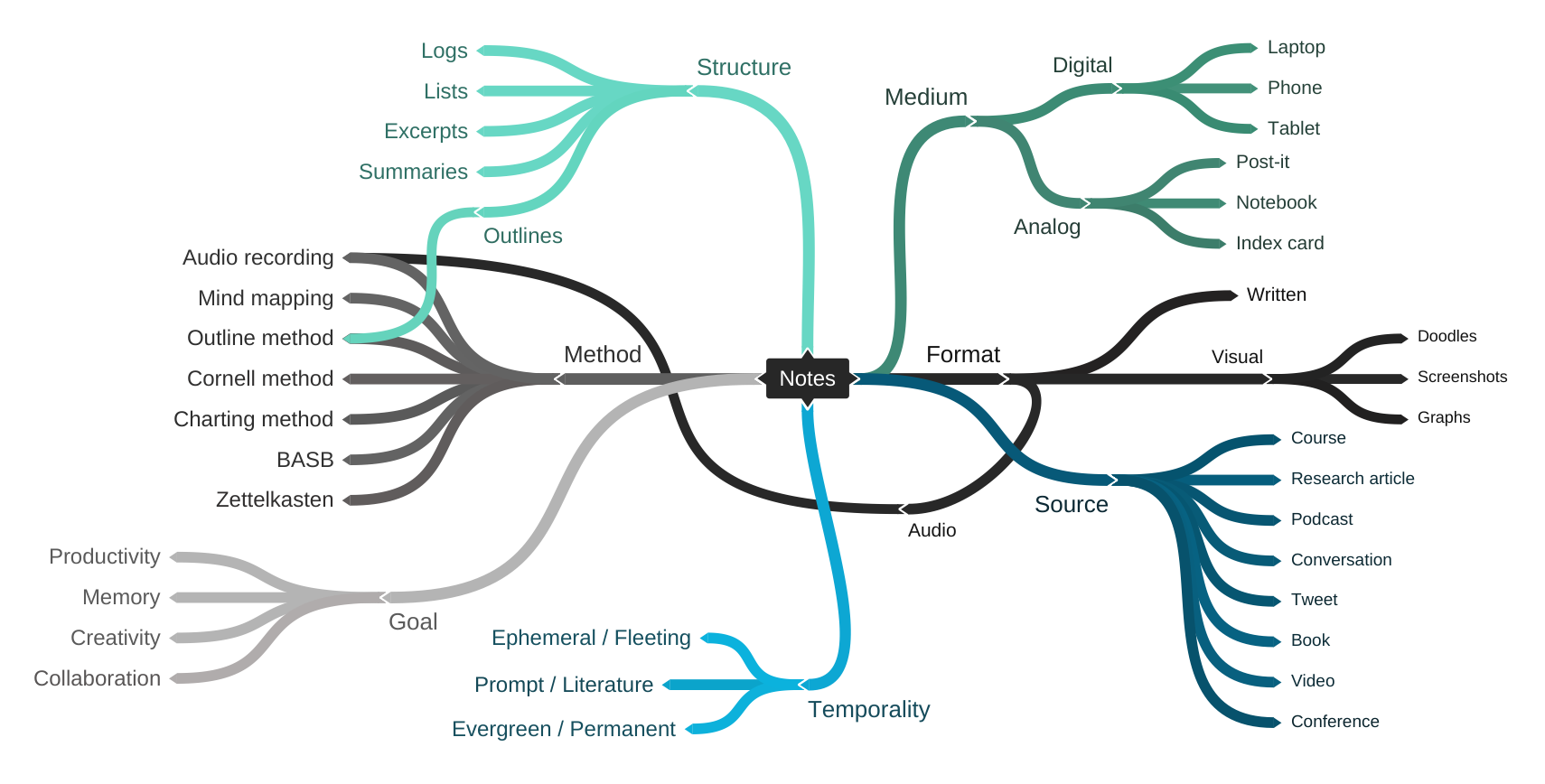

The many ways of classifying notes

I identified seven different taxons, with many classes overlapping with each other. For example, “outline” is both a method and a structure, and “audio” is both a method and a format.

- Medium. Where the note is recorded. This could be digital (on a phone, tablet, laptop) or analog (post-it note, notebook, index card, etc).

- Goal. Why the note is recorded. Notes can be taken with a variety of aims, such as productivity, memory, creativity, collaboration.

- Temporality. When and for how long the note is recorded. Notes can go from quick and ephemeral (“fleeting note”) to living archives you keep on adding to (“evergreen note”).

- Format. How the note is recorded. The note could be written (bullet points, excerpts), audio (voice note), or visual (screenshots, doodles, graphs).

- Method. There is a bit of overlapping with the format, but this looks at the specific method used for taking the note, such as the Cornell method, mind mapping, or Zettelkasten.

- Structure. How the note is arranged. Logs, lists, and excerpts are lower-effort, whereas outlines and summaries are more involved. Again, some overlap with format.

- Source. Was the note generated from a book, a research paper, a newspaper article, a tweet, a podcast, a conversation?

This taxonomy is by no mean exhaustive. Each taxon is missing many classes—for instance, there is an infinity of potential sources for notes—and I excluded some taxons, either voluntarily, such as the specific skills involved in note-taking as defined by Al-Musalli, or because I didn’t think about them.

One of the reasons why I enjoy using Roam as a note-taking tool is its versability. While some formats are not natively supported yet, most methods, structures, aims and temporalities work well within Roam. Want to give it a try? Check out my beginner’s guide to Roam.