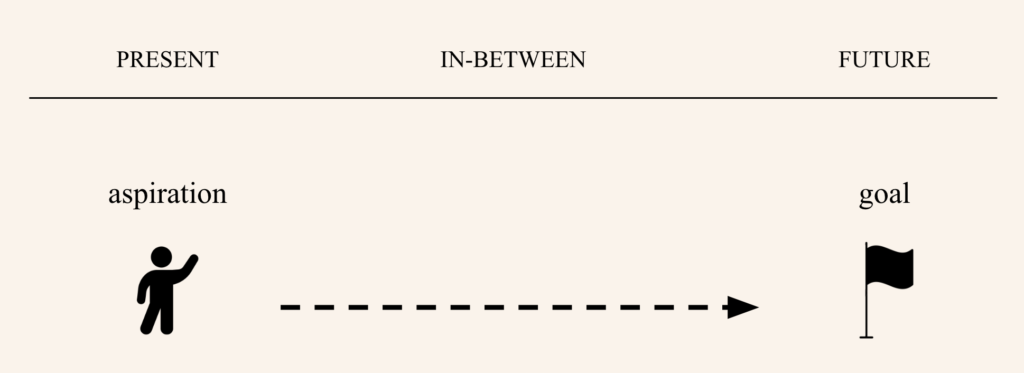

Success is commonly defined as reaching one’s goals. Getting accepted into a prestigious program, building a profitable business, becoming a doctor, completing an online course… Whatever the goal may be, success is simply bridging the gap between where we are and where we want to go.

The Internet and our bookshelves are filled with exhortations to stay motivated, manage our time more effectively, and stick to our plan. If success is so easy to define, why is it then that we often struggle to establish, pursue, and reach our goals?

The way we manage goals is broken, to the point where many people are questioning the very nature of ambition. And it is true that chasing ambitious goals may feel pointless when everything feels so chaotic.

But ambiguity and opportunity are two sides of the same coin. Navigating uncertainty is how we learn and how we change. To flourish in our increasingly turbulent world, it is imperative we foster radical change at a realistic scale. Instead of applying rigid, linear models of goal management, we need to create space for our goals to emerge.

A Tale of Success and Failure

When we talk about goals, we suggest a desired outcome attained through some form of prolonged effort. Goal-setting usually goes like this: we define a target state, and then we map our journey to get there. It all sounds sensible: goal-setting allows you to decide where you want to go, and to define how you will get there.

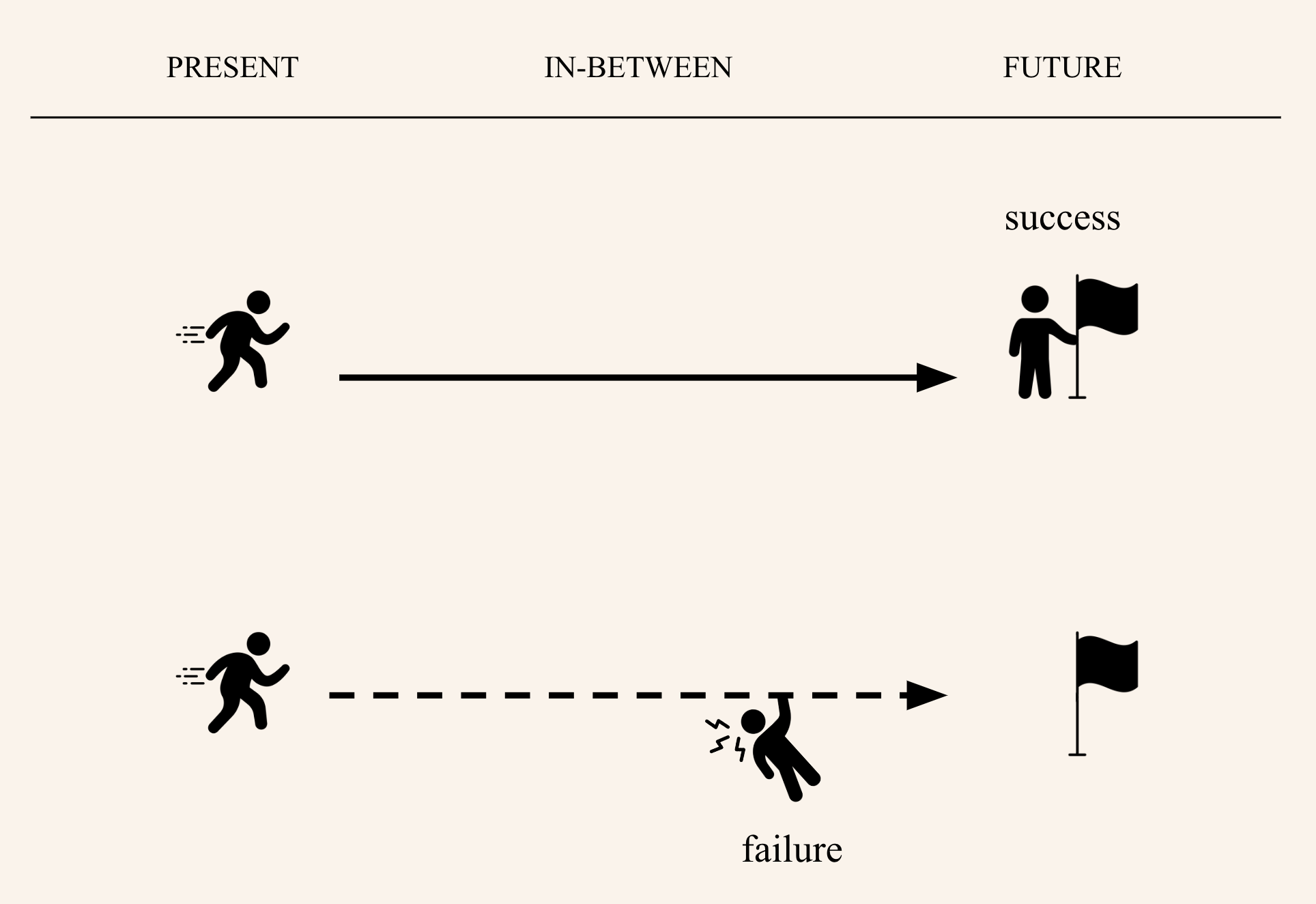

Then, we expect to reach our goal. And this is where things start to go wrong. See, there are only two possible outcomes: either we successfully reach our goal, or we fail.

It’s easy to see why failure leads to disappointment. When any outcome other than the expected one is perceived as failure, it’s no wonder we start questioning our self-worth, wondering what went wrong, or blaming external factors — rightly so or not. Our reaction may vary, but the experience feels the same: distress and doubt.

What’s more surprising is what happens when we successfully reach our goal.

Designed for disenchantment

In the process of working toward a goal, we come to imagine what it will feel like to achieve it. For example, we start thinking: “When I graduate, I will feel accomplished” or “When I launch this product, I will have more free time to spend with my family” or “When I get this job, I will feel like my career is on track.”

Unfortunately, the happiness we feel when reaching a goal is short-lived. Dr Tal Ben-Shahar calls this the arrival fallacy. We give a big presentation, only to go back to our daily routines. We finish a project, then realize there are two more to work on. We receive a promotion, but still feel unsure about our career path. Life doesn’t seem that different after reaching a goal.

It doesn’t help that modern life has created a giant public leaderboard that maintains the artificial need to “keep up” — to persist on climbing the ladder as new rungs are incessantly added.

Because of social media, we compare ourselves to our peers more than ever before. LinkedIn notifies us of the success of not just our colleagues, but all the people we studied with in school. Instagram is a constant reminder of the supposedly perfect lives of everyone in our network.

This proverbial “rat race” feeds into the arrival fallacy: If only we can climb one more step — if only we can get that promotion, give that big presentation, grow our online audience, hire a team, buy that house — then, we’ll finally feel at peace.

But both successful and failed goals end up letting us down, so any expectation seems to be a recipe for disenchantment.

The logical solution would be to let go of our ambitions and altogether abandon the idea of goals. In the words of Peter La Fleur, a character played by Vince Vaughn in Dodgeball (2004): “I found that if you have a goal, you might not reach it. But if you don’t have one, then you are never disappointed.”

This sounds great in theory, but it goes against our very biological makeup. All living species are goal-oriented in nature. In fact, this is the key difference between living organisms and nonlife: all organisms have goals.

These may be very basic goals, such as survival and reproduction, but goals nonetheless. Even sponges collaborate with other species to survive, and plants turn toward the sun to get the most sunlight.* As special as we like to think of ourselves, humans are no different. We are goal-oriented creatures. We need a sense of purpose to drive our actions, to survive and to thrive.

Even so, goal-setting keeps on failing us. We sense that we need goals, but we know something is terribly wrong with the way we define and pursue them.

Here lies the paradox of goals: Setting goals is a guarantee for disillusionment whether we reach the desired state or not, and yet working toward goals is an important part of evolving as a person. How can we resolve this paradox?

From Goals to Growth Loops

Notice the vocabulary we use to talk about goals. Goals drive us forward, we set out to achieve our goals, we make progress toward a goal. Those are called orientational metaphors. In our collective psyche, goals rely on a sense of movement. And that’s not wrong. But we may be misguided as to the direction of this movement.

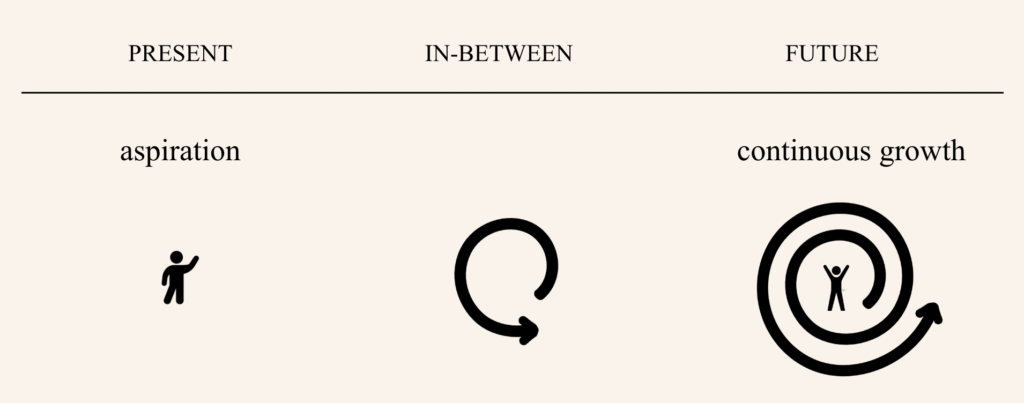

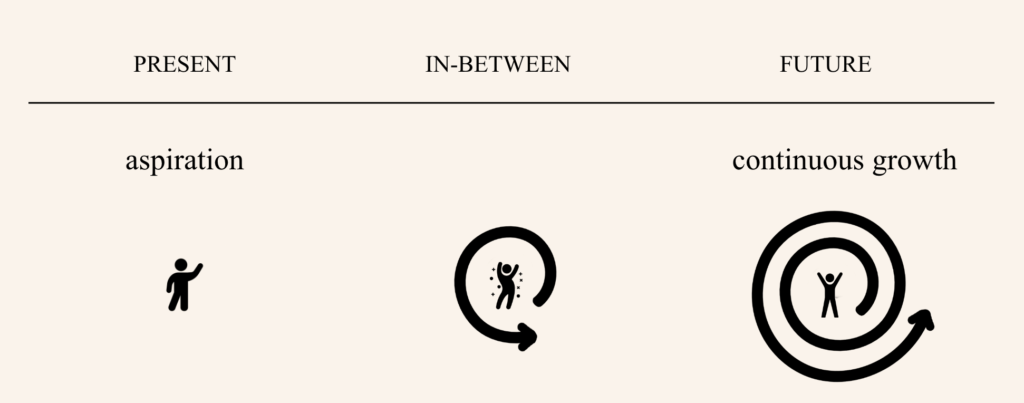

Instead of a linear scale progressing from a present state to a desired outcome (the classic “up and to the right”), goals should be conceived as cyclical.

Let’s break it down.

Two key ingredients are required to pursue a goal: the will and the way. The will is our motivation — a reason why we want to achieve the goal, which gives us the energy to push ourselves. The way is our ability to map out the steps to take and acquire the skills we need to execute the required actions.

In simple situations, or when following a default path as prescribed by society, the will and the way are fairly easy to define. For instance, your goal might be to get a promotion, and the steps might even be outlined in a corporate handbook with a clear rating scale.

However, life is rarely this simple — and, in fact, you may not want to live such a life where your goals are predefined and the way to achieve them is preprocessed for you.

What if we don’t know where we are and where we want to go? What happens when the will and the way are unclear?

It is tempting during such liminal moments to cling on to a ladder — any ladder — to regain an illusory sense of control. As long as there is movement, it feels like progression. But this temporary hack is rarely sustainable. Soon, we start noticing the cracks.

We have the nagging sense of dread that we are on the wrong path, but we are not sure what to do next. In our modern world with its infinity of potential goals to pursue, which ones should we explore? How do we know which one is right for us?

As you can see, linear goals are inherently fragile.

The solution, inspired by nature itself, is to design growth loops by practicing deliberate experimentation.

As Nassim Taleb puts it: “It is in complex systems, ones in which we have little visibility of the chains of cause-consequences, that tinkering, bricolage, or similar variations of trial and error have been shown to vastly outperform the teleological — it is nature’s modus operandi.”

A teleological approach consists in choosing your next action based on its end goal. In contrast, “bricolage” (from my native language, French), can be roughly translated to “making small changes to something in an attempt to improve it.” If the first attempt works, that’s great. If it doesn’t, we try again.

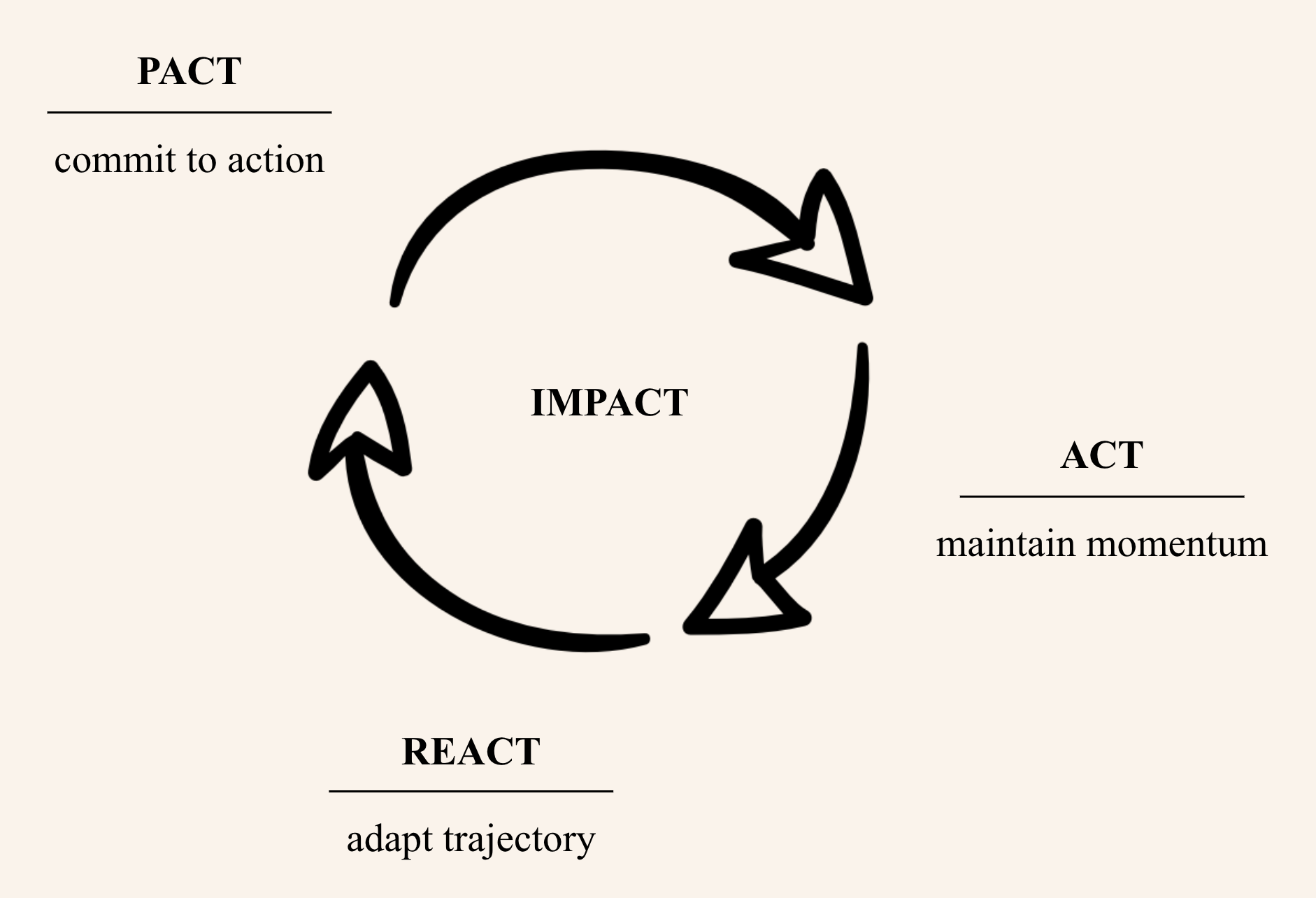

This process sets in motion a cycle of deliberate experimentation: First, we commit to an action. Then, we execute the target behavior. Finally, we learn from our experience and adjust our future actions accordingly.

Each cycle adds a layer of learning to how we understand ourselves and the world around us. Instead of an external destination, our aspirations become fuel for transformation. We don’t go in circles, we grow in circles. Goals turn into growth loops.

Our ancestors instinctively knew of this circular model of growth. In many cultures, the wheel is a symbol of growth and success. The cyclic ages of Hindu cosmology, the wheel of life in Buddhism… The wheel combines the idea of progress and wholeness: it is complete and yet it keeps on moving. It represents the perpetual change and transitory nature of life.

This cyclical model also aligns with the way our mind naturally works. The brain is built on a giant perception-action cycle with a circular flow of information between the self and the environment, and a system constantly conveying whether a signal should be intensified or stopped.

This feedback loop is so well established, it is considered the theoretical cornerstone of most modern theories of learning and metacognition.

Instead of ignoring ancestral wisdom and modern scientific knowledge by blindly pursuing goals at the expense of our mental health, we should consider going back to a circular model in which goals are continuously discovered and adapted — in conversation with our inner self and the outer world.

An Antidote to Uncertainty

We cannot think of goals without thinking of space and time. Space: where am I and where do I want to be? Time: how long will it take me to cross that gap? The uncertainty that surrounds the space-time continuum of goals is not just conceptual — it’s deeply emotional. For instance, a big gap may feel scary. Not moving fast enough can give us time anxiety.

By turning goals into growth loops, we can embrace the idea that achievement is simply the continuation of the learning cycle itself. Sure, the future is uncertain, but our personal growth is inevitable.

Cycles of deliberate experimentation can help us let go of the chronometer. Growth loops may feel slower and they don’t come with a shiny finish line, but each layer of learning contributes to our ongoing success. And, perhaps paradoxically, we can often progress faster by allowing for the possibility of getting things wrong and facing challenges.

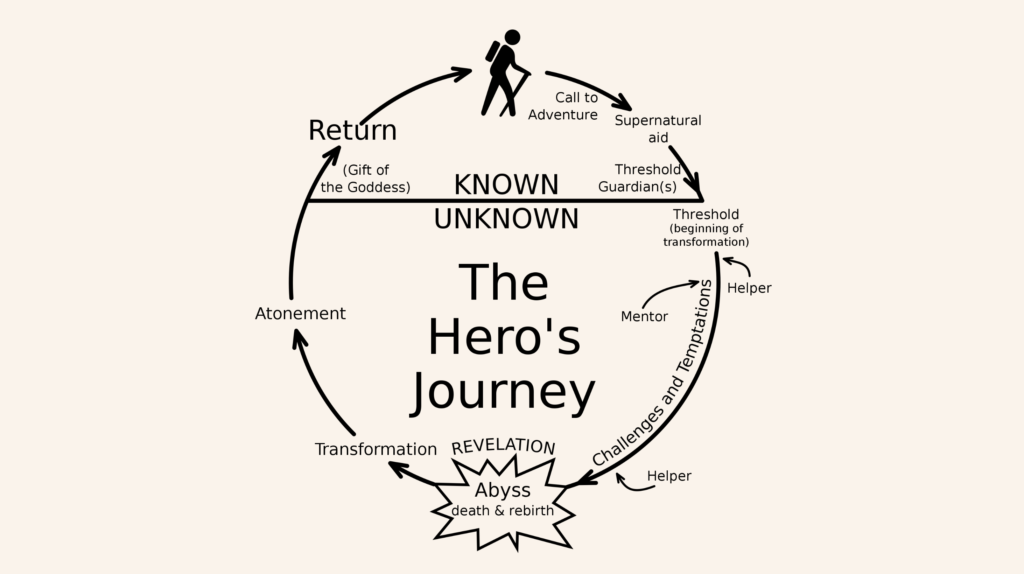

This is the archetypal hero’s journey, where the hero embarks on an adventure, equipped with their current knowledge, and returns transformed by their experience.

Some of the most successful endeavors are based on growth loops. The scientific method relies on formulating hypotheses, testing them, and implementing the results into the design of future experiments. Sports teams commit to a strategy, apply it during a game, and keep on adapting their approach through each cycle of training and competition.

If you like cooking, you already apply growth loops in at least one area of your life: chefs experiment by adding an ingredient, tasting to see if it works, and keeping or discarding the change depending on the result over many attempts.

Beyond the outcome, growth loops allow us to truly enjoy the journey instead of falling prey to the arrival fallacy. The space between where we are and where we want to be is not a purgatory anymore, it’s a playground — a place we can fill with learning opportunities and, yes, even fun!

How to Design Growth Loops

Growth loops are extremely simple: we simply need to commit to action, monitor our progress, and reflect on the results so we can keep on adding layers of learning through each cycle. There is no need to worry about the ultimate destination: success emerges as a result of the repeated experimentation and learning.

Here’s how you can design your own growth loops:

- Pact. Choose an action you want to commit to. It could be something you’ve always wanted to experiment with, or something you’ve just recently heard about. It could even be something you suspect you won’t enjoy, but don’t know for sure because you’ve never given it a proper try. Your pact needs to be Purposeful (something you care about), Actionable (something you can do today), Contextual (based on your current situation), and Trackable (a yes/no action).

- Act. Now, just do it! You need to stick to that action for long enough so you can collect sufficient data. This requires monitoring your progress (a good old habit tracker can do the job) and taking care of your mental health so you can maintain motivation and momentum.

- React. Once you have enough data (which will depend on the nature of your pact), you need to start regularly reflecting on your progress. Is your current pact having a positive impact on areas of your life you care about, such as health, well-being, or relationships? How does it feel to perform this action? Is it energizing or draining? Do you want to keep on going with this pact for one more cycle, or should you tweak it or abandon it?

- Impact. Keep on going through the first three steps of the cycle (Pact, Act, React), and you will start noticing the impact on areas that feed into the ultimate goal: living a happy, healthy, fulfilling life.

Through this process, we develop our own mental models, collect personal stories, and become not a radically different person, but simply the most intentional version of ourselves. This way, success becomes a form of self-cultivation — the development of personal wisdom and inner strength based on our experiences.

Life itself is movement, a perpetual transformation. If we are going to spend most of our time navigating this in-between, figuring out where we are and where we want to grow, we may as well enjoy the dance with uncertainty. Here lies the solution to the paradox of goals.

* To be clear: at a macro-level, evolution has no goal. We evolve as species through a blind game of trial-and-error, where the behaviors most prone to supporting reproduction automatically become more prevalent. However, at the level of each organism, our actions are driven by conscious and/or unconscious goals.