Worry is traditionally seen as a negative emotion. But is it possible worry has a positive function, and that we just don’t tend to use it well? Physician and researcher Martin L. Rossman argues that worry is actually an adaptive function to better solve problems and imagine creative solutions. And worrying well is a skill anyone can learn.

Worry is a product of imagination, one of the key mental faculties that separate humans from other living beings. Both worry and imagination are based on remembering things from the past and projecting ourselves into the future. If we didn’t have an imagination, we wouldn’t worry. They’re two sides of the same coin.

Dr Martin L. Rossman jokes that this is what lobotomies are about—and to a certain extent, most medications treating anxiety. If we could perform a safe “imaginectomy”, we could get rid of worry… At the expense of our imagination. Instead of getting rid of our imagination—and thus our creativity—we should try to use it better.

The difference between worry, anxiety, and stress

While worry, anxiety, and stress are closely related, here are important differences to be aware of in order to start worrying well.

- Worry. A repetitive/ruminative form of thinking about the future or the past. Paradoxically, because many of the things we worry about may never happen, or may have not objectively happened, our mind may interpret it in a way that assumes worrying was what prevented the negative event to happen. Worry happens in the prefrontal cortex—the thinking part of the brain.

- Anxiety. An uncomfortable feeling of fear, apprehension, or dread, often in the gut or chest, accompanied by physical symptoms such as rapid heartbeat and sweating. Anxiety comes from the limbic system, also called the emotional brain.

- Stress. A physical response (fight or flight) to a threat, real or imagined. In our modern life, many threats are imagined, but stress was designed by nature to ensure our survival. It’s characterised by an adrenaline and cortisol surge, and increased blood levels to your muscles.

All of them are not intrinsically bad. For instance, short-term anxiety can be a sign something is not quite right; a symptom you need to listen to in order to bring what causes your anxiety into awareness. Maybe you are uncomfortable with a situation at work, maybe you have been avoiding looking into your finances. Similarly, stress, as a response to a threat, is a built-in survival mechanism. If the threat is real, your body getting into stress mode is a good thing.

Both are bad if they’re either chronic or too intense. A panic attack is a form of acute anxiety which is extremely distressing for people who suffer from it. Chronic stress has a terrible impact on the body and the mind. And the same goes with worry: it can be positive or negative.

Functional worry versus futile worry

Worrying well may sound like an antinomy. Functional worry (“good” worry) anticipates and solves problems. It is functional to worry about certain future events instead of burying your head in the sand. For instance: “I’m worried about whether I’ll be able to pay for my kid’s education” or “I worry I won’t be able to find a good school”—these are valid worries. The main question you can ask yourself to figure out whether a worry is functional or not is: “Is it likely that I could do something about this?”

Futile worry (“bad” worry) is circular, habitual, almost magical. It doesn’t lead to any solution, and it makes you feel scared, which is not helping since the fear makes it harder for you to use your brain. Dr Rossman gives the example of what happened in 2012: “I’m worried the world is going to end in December.” Well, that’s something you may as well put on your “bad” worry list—even if it’d been true, there’s really not much you could have done about it.

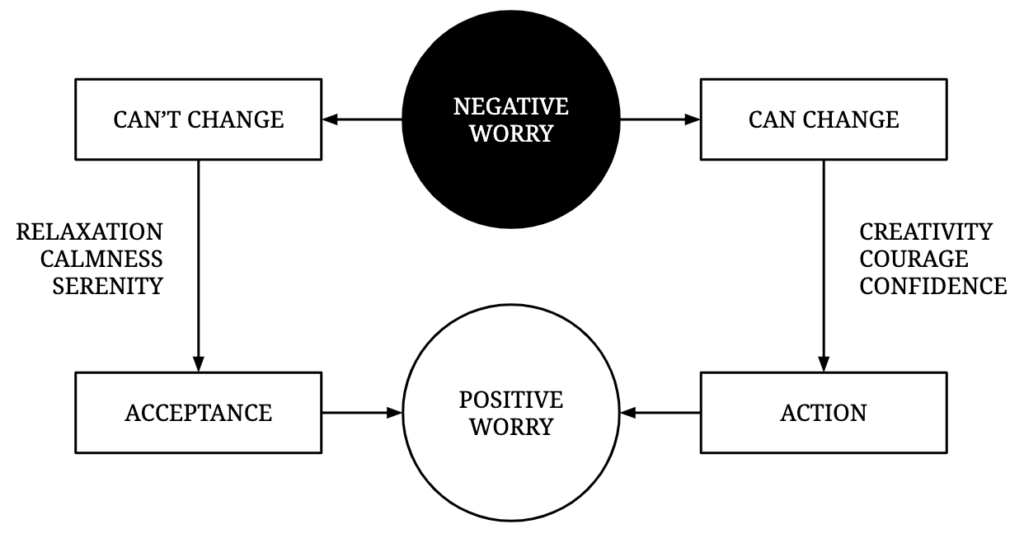

Beyond your ability to do something about it, how do you tell the difference in practice? Dr Rossman cites the Serenity Prayer: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference.” For people who are not religious myself, he recommends removing the “God” part and focusing on everything that comes after. It’s a simple mantra to help you separate worries into things you can change and things you cannot change.

If you’re not sure about a specific worry, how do you get more wisdom?

- Talk to people you think are wise. These could be friends, teachers, people who have helped you navigate complex situations in the past.

- WWJ/B/DL/Y do? What would Jesus, Buddha, the Dalai Lama, or Yoda do? When you don’t have access to a wise friend or teacher, you can use this imaginary technique. We usually don’t struggle to give advice to our friends when they come to us with their worries, but we’re struggling to help ourselves in the same way. What would somebody you imagine is genuinely wise do in this situation?

- Inner wisdom imagery. It may sound strange, but you could even get into a relaxed, meditative state, and imagine you are walking in a garden with a person you consider wise (maybe your wise grandma) and are having a conversation with them. This exercise can help you approach your worries from a place of wisdom.

Worrying well is about tapping into the wisdom of real or imagined people, you can turn your negative worry into a positive one—whether a worry you accept, if the circumstances are out of your control, or one you can take action upon. You can watch the full lecture by Dr Rossman here.