We often tend to prefer complex solutions over simple ones; complicated marketing jargon over clear explanations; multi-steps implementations over more direct execution. Complexity can lend an aura of authority to products, which marketers are exploiting to project authority and expertise. Complex processes can also delay decision-making, giving us the illusion of productivity. Why is it that we struggle so much to embrace the power of simplicity? And how can we balance complexity and simplicity?

Nothing left to take away

Simple thinking can lead to safer plans, better communication, and easier execution. The power of simplicity is apparent throughout history, where strategists and artists alike strived for simplicity:

- Keep it simple, stupid. Allegedly coined by aircraft engineer Kelly Johnson, the KISS principle makes simplicity a key goal in design by stating that most systems work best if they are kept simple. One day, Kelly Johnson handed his team of design engineers a handful of tools, with the challenge that the jet aircraft they were designing must be repairable by an average mechanic in the field under combat conditions, only using these tools—forcing them to keep the design stupidly simple.

- Less is more. Famous architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who is considered one of the pioneers of modernist architecture, always kept repeating this aphorism to whoever would hear him: less is more. His approach was to arrange the necessary components of a building to create an impression of extreme simplicity, sometimes repurposing some elements so they would serve several purposes.

- Simplify, then add lightness. One of the leaders of the minimalist movements, Colin Chapman, the founder of Lotus Cars, urged his designers to “Simplify, then add lightness.” Designer of the world’s first ever stressed monocoque racing car, built with an entire chassis in aluminium sheet, Colin Chapman strived to use as few parts as possible in his cars. Today, many product designers still use the magic of subtraction to innovate.

In literature, the power of simplicity is also around. When trying to solve a crime, the most famous fictional detective believes that “the simplest explanation is often the most plausible.” Antoine de Saint Exupéry also wrote: “It seems that perfection is reached not when there is nothing left to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.”

The allure of complexity

Despite the benefits of simplicity, we still often tend to overcomplicate our decisions. Dutch systems scientist, Edsger Wybe Dijkstra, considered by many a pioneer of computer science, once said: “Simplicity is a great virtue but it requires hard work to achieve it and education to appreciate it. And to make matters worse: complexity sells better.”

Marketers are well aware of the allure of complexity, and exploit our complexity bias by making their products sound more sophisticated and their brand more authoritative. Jargon is used to impress rather than to inform consumers.

Let’s read these: “Utilising a Vita-Ciment® Complex, Kérastase Resistance Bain Force Architecte, is a strengthening shampoo that has been specially formulated to cleanse and fortify damaged hair at erosion levels 1-2” or “Enriched with amino acids, a wheat protein derivative and ceramide R, it smooths and strengthens the hair, whilst creating an even surface and a hydrophobic layer which protects the hair from humidity”—do you understand what is being said? Most people wouldn’t. No matter, both of these are popular shampoos.

We associate complexity with expertise, innovation, and authority. Paradoxically, we will often trust products touting complicated statements such as the ones above more than a simple, straight-to-the-point message. But complexity is not always all smoke and mirrors. In fact, a little bit of complexity can do wonders when it’s balanced with simplicity.

Complexity is a moving target

As we have seen, simplicity can lead to innovative thinking and improve decision-making, and complexity is often used to impress rather than to be helpful. We all tend to easily fall prey to the complexity bias. This is not to say all complexity should be eradicated from our lives. Complex experiences can be enriching and exciting.

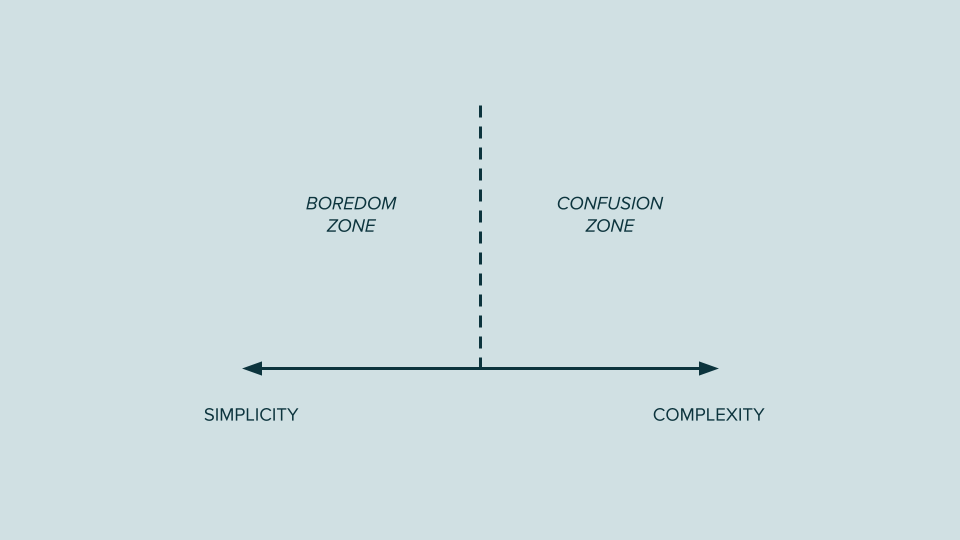

In Living with Complexity, Professor Donald Arthur Norman wrote: “We need complexity even while we crave simplicity. Some complexity is desirable. When things are too simple, they are also viewed as dull and uneventful. Psychologists have demonstrated that people prefer a middle level of complexity: too simple and we are bored, too complex and we are confused. Moreover, the ideal level of complexity is a moving target, because the more expert we become at any subject, the more complexity we prefer.”

Rather than fully eliminating complexity, we should be mindful of the way we manage it in our life, in our work, and in our creative projects. Watching a complex movie, enjoying the complex aroma of a cup of tea, or studying a complex topic can all give us rich experiences; on the other hand, an overly complex project plan may lead to mistakes and hide fundamental flaws.

Finding the right balance is a delicate exercise. Ask yourself: is this level of complexity adding to the experience, or overcomplicating it? What could be removed without perverting the essence of the experience? Is complexity in this particular case a feature or a bug? If you are working on a project, ask your teammates and users: is this too complex and confusing? Is this too simple and boring? Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication—it may feel paradoxical, but it takes some complex questions to reach it.