Have you ever had a teacher who was very smart but terrible at teaching? An expert who used so much jargon you could not follow their explanation? This is called the “curse of knowledge”, a term coined in 1989 by economists Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein, and Martin Weber.

It’s a cognitive bias that occurs when someone incorrectly assumes that others have enough background to understand. For example, your smart professor might no longer remember the challenges a young student faces when learning a new subject. And the expert might overlook the need to simplify concepts, assuming everyone knows what they know.

As Baruch Fischhoff, professor at the Institute for Politics and Strategy at Carnegie Mellon University, puts it: “It might be asked whether this failure to empathize with ourselves in a more ignorant state is not paralleled by a failure to empathize with outcome-ignorant others.”

When familiarity leads to false assumptions

One of the most famous illustrations of the curse of knowledge is a 1990 experiment which was conducted at Stanford by a graduate student named Elizabeth Newton. In this study, she asked a group of participants to “tap out” famous songs with their fingers, while another group tried to name the melodies.

When the “tappers” were asked to predict how many of the songs would be recognised by the listeners, they would always overestimate. The “tappers” were so familiar with what they were tapping, they assumed listeners would easily recognize the melody.

These findings have interesting implications. For example, research suggests that sales people who are better informed about their product may be at a disadvantage compared to less-informed sales people.

This is because the better-informed sales people fail to adjust their pitch to the level of knowledge of their prospects. Since the knowledge gap is smaller, lesser-informed sales people also find it easier to align on a pricing that both parties deem acceptable.

Understanding the curse of knowledge is one thing, but how can you actively overcome it in your everyday interactions? By implementing simple strategies to bridge the knowledge gap.

How to bridge the knowledge gap

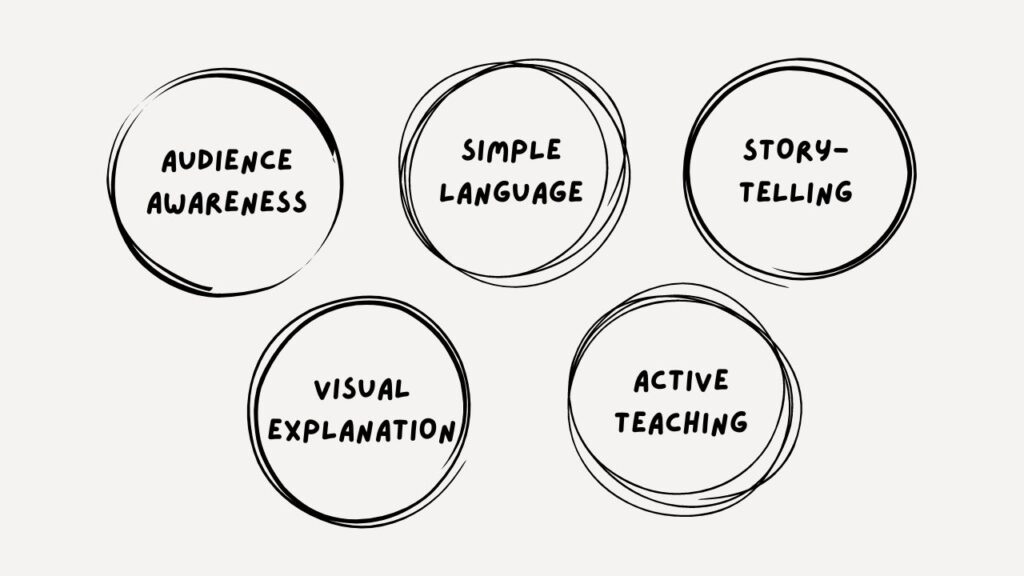

You can avoid the negative effects of the curse of knowledge by constantly questioning your assumptions as to how much exactly your audience knows.

- Get to know your audience. Try to know how much they know. If you’re talking to a friend or colleague, assess the extent of their knowledge before starting your explanation. If you’re talking to potential customers, ask a few questions before starting your sales pitch.

- Simplify your language. Don’t hide behind jargon and complex terminology. Use simple language and clear examples to make your point easier to understand even with limited knowledge.

- Use storytelling. Stories can make information more relatable and memorable. Relate complex concepts to familiar experiences. Analogies and metaphors can also make abstract ideas more concrete and understandable.

- Show, don’t tell. A picture can be worth a thousand words. Instead of a lengthy explanation, see if you can create a visual, a graph, or an illustration that conveys the same content in a more accessible way.

- Engage in active teaching. Encourage questions and discussions. Pause at every step to ensure the person is following. By engaging your audience, you can better gauge their level of understanding and adjust your explanations accordingly.

What’s great about simplifying your explanations is that it reinforces your own knowledge. If you can’t explain something without using complicated jargon, you’re probably not as familiar with it as you think. Making the effort to explain concepts in simpler terms ensures you truly understand them.

We also remember things better when we create our own version of the material. The Generation Effect shows that actively manipulating new information helps form relationships between concepts, making them easier to recall when needed.

Being aware of the curse of knowledge is the first step; actively trying to avoid it and improving your own learning process is the second. By doing so, you’ll enhance your communication skills but also deepen your understanding and retention of the information.

This conscious effort to bridge the knowledge gap can lead to more effective teaching, better learning outcomes, and more meaningful interactions—win, win, win.