Scholars have discussed the mechanics of persuasion since ancient times. Persuasion encompasses every aspect of culture, with rhetoric as a crucial tool to influence every sphere of society, from mundane negotiations to big national debates. One could argue any form of communication is a form of persuasion. Whether through writing or talking, at home or at work, with friends or customers, chances are you spend a good amount of your time trying to persuade someone of something. In Rhetoric, Aristotle defines three main ways to persuade people: ethos, pathos, and logos.

Peter Gould famously said: “Data can never speak for themselves.” Even with the most solid evidence for your argument, facts alone are rarely enough to convince someone. Instead, you need to use rhetorical appeals to deliver your message. Researchers have described how you can use these rhetorical appeals to credibility, emotions and logic in order to increase their persuasiveness. Let’s have a look at these together.

“Persuasion is clearly a sort of demonstration, since [people] are most fully persuaded when we consider a thing to have been demonstrated.”

Aristotle.

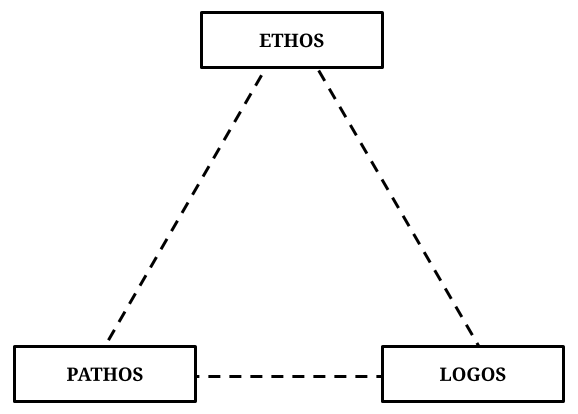

The three modes of persuasion

Aristotle called these the three artistic proofs. Combined together, they allow any orator to make their message more powerful, and increases their likelihood to convince their audience. While they are extremely advantageous skills to master in order to persuade people, they’re also useful in order to understand how you’re being persuaded yourself.

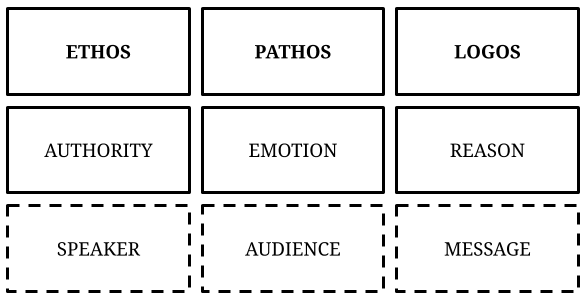

While ethos is focused on you, logos is focused on the message, and pathos on the audience. The three modes of persuasion are deeply intertwined and work best when used together.

And it all starts with knowing your audience. What makes them tick? What do they value? What beliefs do they hold? In order to construct a convincing argument and persuade people to think in a different way, you not only need to know what your point is, you need to know who you want to persuade. Only then, you can use the three modes of persuasion to appeal to authority, emotions, and logic.

Ethos: appeal to authority

Ethos is all about building trust. It can be defined as how well you convince your audience that you are qualified to speak on the subject. It may seem obvious that if someone is listening to a talk about design, they’re more likely to believe a professional designer than a professional cook, but there are many ways to create credibility.

The most obvious one is to use credentials, either yours or by being introduced by a prominent authority in the field who can vouch for your expertise. The perceived power of credentials is partly why people care so much about their job titles. We tend to unconsciously apply unofficial rubrics to evaluate a person’s credibility based on apparent qualifications. And this is also why a job title may often not be enough to establish your ethos.

Beyond your job title, mention your actual achievements. Instead of saying you’re a lead designer at a big company, mention a couple of major campaigns or products you worked on and what success you had. Instead of saying you’re a developer, mention how many times one of your project was starred on GitHub. It may feel like bragging, but it’s an important part of establishing your ethos. “Been there, done that” is an authentic and ethical way to build trust.

Another important aspect to bolster your credibility is to create a sense of mutual identification with your audience. Between two speakers with the same achievements and credentials, people will tend to trust the one they can connect with at a deeper level.

In Perspectives on Medical Education, researchers share an interesting example.

"While burnout continues to plague residents, medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. Medical educators owe it to their residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service."

By using similitude, the new version builds rapport with the audience, thus increasing the credibility of the speaker as part of the medical community:

"While burnout continues to plague our residents, medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. We owe it to our residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service."

The first version creates social distance. The second creates social connection. To establish your ethos, go beyond your official credentials: share concrete achievements, and encourages a sense of cohesion with the audience.

Pathos: appeal to emotions

The terms empathy, sympathy and pathetic are all derived from the word pathos, which means “suffering” or “experience” in Greek. It consists in appealing to your audience’s emotions—to make them feel what you want them to feel by triggering specific emotional reactions. Great storytellers are usually skilled masters of this mode of persuasion.

Pathos doesn’t have to be overly dramatic. In fact, a lack of subtlety may hurt your argument. Instead, you can evoke pathos through an emotional tone, an uplifting story, and by using meaningful language, such as metaphors. Appeal to your audience’s imagination through storytelling such as personal anecdotes.

It is more likely people will care about what you have to say if you seem to care. Showing passion and emotion can greatly impact your audience’s mindset.

Let’s have another look at our previous example.

"While burnout continues to plague our residents, medical educators have yet to identify the root causes of this problem. We owe it to our residents to delve into this area of inquiry to secure their wellbeing over their lifetime of clinical service."

Using the concepts of duty and service taps into the sense of responsibility of the audience. It grabs people’s attention by inspiring action. As you can see, focusing on the vocabulary you use—adding an implied level of meaning—can have a profound effect on the resulting narrative.

One of the most famous examples of pathos used in a speech is “I Have a Dream” by Martin Luther King.

“I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. And some of you have come from areas where your quest—quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.”

Remember, you don’t need to go overboard to elicit an emotional response. In order to work, pathos needs to be used sparingly, where it has the strongest impact, and in a way that feels natural. If forced, pathos can have the opposite effect, making people distance themselves to avoid the awkwardness of your emotional outpouring.

Logos: appeal to reason

Finally, you obviously need for your message to make sense—or at least to seem logical. Unfortunately, it is possible to use the three modes of persuasion to convince an audience of something wrong. It’s more evident than ever in today’s world where false information spreads like wildfire by misusing ethos (apparent authority), pathos (emotional storytelling), and logos (superficial logic).

Logos is the way you present your arguments in a logical order, which must feel so straightforward and rational that no other alternative can be conceived by your audience. Ideally, these steps should follow each other so naturally that your audience arrives at the logical conclusion just before you announce it yourself, giving them the feeling of figuring it all out themselves—which is intellectually gratifying.

While facts are important, a lot of the power you will get from logos lies in how you connect these facts. The syllogism “All men are mortal; Socrates is a man; therefore, Socrates is mortal” is a famous example of such logical connections between facts to arrive to an irrefutable conclusion. But, as you know, such connections can be used to arrive at a false conclusion (“All horses have four legs; my dog has four legs; therefore, my dog is a horse”).

This is why the mere appearance of logic should not automatically inspire trust when you’re the one being persuaded. Pathos can be misleading, especially when you’re not familiar enough with the subject matter. When combined with a sense of authority from the speaker and the use of emotional triggers, it may be difficult to tell true from false.

How to use ethos, pathos, and logos

The three modes of persuasion can be used in any form of communication. Next time you write an article, post on social media, record a podcast, or give a presentation at work, remember to use ethos, pathos, and logos to better persuade your audience.

- Establish ethos. Ethos starts long before you begin to make your case. You need to build your reputation by developing deep expertise in the topics you want to address. Don’t wait for people to find out you know a lot about these things. Put yourself out there. For example, I have a deep interest in mindful productivity. The reason why companies book my workshops is because they read enough of my articles to be convinced I know what I’m talking about. When it comes to the content of your speech or article, make sure to know your audience so you can better connect with them through a sense of similitude. You can reference common experiences, cite publications they read, quote authors they admire.

- Develop pathos. Pathos is all about your ability to tell stories. First, choose which emotion you want to elicit. While some people are great at bringing people on a rollercoaster of emotions, it’s often better to stick to one main emotion. Second, decide which part of your message you want to use as an emotional trigger. Pathos works best when used sparingly. Finally, use some of the many rhetorical tools at your disposal to bring the emotion to life: rich words, analogies, metaphors, humour, surprise. Your body is also a great communication tool. Make eye contact with your audience, and match your gestures to the emotion. If you’re giving a presentation, another way to create emotion is to use visuals.

- Convey logos. With logos, your goal should be to make your message logical and understandable. Avoid technical jargon and stick to plain language. Do not hide behind complicated words. Be as explicit and concrete as possible, using examples and comparisons with facts the audience is already familiar with. Outline each steps and connections in your reasoning. Insist on the most important points. Again, if you have slides, getting visual can greatly help convey logos with diagrams and charts.

Ethos, pathos, and logos should not necessarily be used in that particular order. While it’s commonplace to start by establishing ethos, you should live up to it during the entirety of your message. And, in some cases, you may want to start with an emotional anecdote to set the stage for the rest of your story.

As a master of logical reasoning, Aristotle believed that logos should be the most important of the three modes of persuasion, but he admitted that in reality it’s not enough to use logos only. Does the audience respect you? Does your message evoke emotions? Does it make sense? If you can answer yes to all three questions, you’re well on your way to persuade your audience.