Do you know someone who always seems to jump to conclusions? While this behaviour may be more obvious in some people than in others, we are all prone to it. In fact, doctors themselves often jump to conclusions: “Most incorrect diagnoses are due to physicians’ misconceptions of their patients, not technical mistakes like a faulty lab test,” writes Dr Jerome Groopman in How Doctors Think. Why do we do it, and how can we avoid jumping to conclusions?

The psychological term for jumping to conclusions is “inference-observation confusion”, which is defined as when people make an inference but fail to label it as one, ignoring the risk involved. The inference-observation confusion happens when we fail to distinguish between what we observed first hand from what we have only assumed. As a result, we reach unwarranted conclusions without having all the facts.

Often, jumping to conclusions comes from good intentions. To sound compassionate and invested in what someone is telling us, we may interrupt them by saying “wow”, “what a shame”, or “I know what you’re going to say!” When, in fact, we have no idea how the person wants us to feel nor what they are going to say next. In The Lost Art of Listening, Dr Michael Nichols explains how such assumptions may achieve the opposite of our goal: instead of sounding supportive, we may come across as dismissive.

The story of the “Gerbil-Caused Accident”, described by Jan Harold Brunvand in his Encyclopedia of Urban Legends, is a perfect illustration of well-intended inference-observation confusion. In the story, a woman is driving to her son’s show-and-tell session at school, with a pet gerbil in a box on the passenger seat. The gerbil escapes and starts crawling up her leg inside her pants. The woman pulls over, gets out of the car, and begins to jump up and down, shaking her leg to get rid of the gerbil. A passerby thinks the woman is having a seizure, so he approaches her and wraps his arms around her to help. Another passerby sees the struggle, and assumes the first passerby is an attacker, so he punches him the face. The gerbil finally gets out of the woman’s pant leg, and she tries to explain what really happened.

The three types of inference-observation confusion

While we often jump to conclusions with good intentions, there are three main cognitive distortions that account for most inference-observation confusions.

- Mind reading. When we infer a person’s probable thoughts from their behaviour and nonverbal communication. For instance, a manager asks an employee if they know about a file that has disappeared. The employee starts looking away or appears to be uncomfortable, and the manager infers that they must be responsible for the file’s disappearance, even though there are other potential explanations, such as the employee feeling unjustly accused, or them knowing about the person responsible but not wanting to rat them out.

- Fortune telling. When we predict an outcome before we have enough evidence. For example, when we tell ourselves there is no point in starting a diet because we will break it anyway, or when we don’t even attempt to participate in a competition because we are certain there is no way we will win. These inflexible expectations for how things will turn out before they happen often prevent us from taking action.

- Labelling. When we use overgeneralizations by labeling all the members of a group with the characteristics seen in some, or when we assign a label to someone or something based on the inferred character of that person or thing. For instance, someone who committed a crime becomes a criminal. We also often label ourselves, which makes use jump to conclusions when it comes to our own abilities.

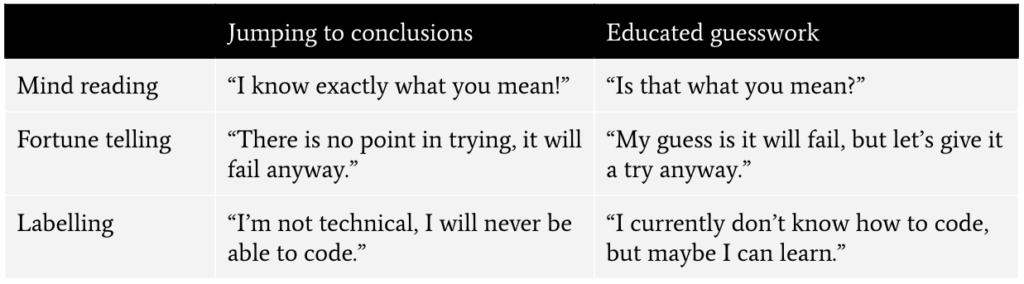

Whether we practice mind reading, fortune telling, or labelling to jump to conclusions when it comes to ourselves or others, each subtype of inference-observation confusion often leads to erroneous conclusions. While our instincts can be powerful tools, it is crucial to manage them and to question instinct-driven conclusions.

The art of educated guesswork

That is not to say you should never draw any conclusions—which would be pretty unpractical. But there is a balance between the two extremes of jumping to conclusions or not drawing any conclusion at all. As Samuel Butler (the novelist, not the 17th-century poet) said: “Life is the art of drawing sufficient conclusions from insufficient premises.”

Instead of jumping to conclusions, we can hold our instinctive thoughts in mind, while leaving enough room to explore alternative conclusions. This can be achieved by shifting the way we phrase our instinctive thoughts.

To avoid mind reading, replace “I know exactly what you mean!” by “Is that what you mean?” For fortune telling, say “My guess is it will fail, but let’s give it a try anyway” instead of “There is no point in trying, it will fail anyway.” Finally, “I currently don’t know how to code, but maybe I can learn” will lead to a better growth mindset than “I’m not technical, I will never be able to code.”

Prince Charles once said: “As human beings, we suffer from an innate tendency to jump to conclusions, to judge people too quickly, and to pronounce them failures or heroes without due consideration.” But I prefer what a good friend of mine likes to say: “Don’t jump to conclusions. You never know where you might land.”