In French, “cultiver son jardin intérieur” means to tend to your internal garden—to take care of your mind. The garden metaphor is particularly apt: taking care of your mind involves cultivating your curiosity (the seeds), growing your knowledge (the trees), and producing new thoughts (the fruits). On the surface, it’s a repetitive process. You need consistency and patience. But each day tending to your “mind garden” is different: discovering a new learning strategy, having a eureka moment, connecting the dots between two authors, getting involved in a lively conversation with an expert.

“So plant your own gardens and decorate your own soul, instead of waiting for someone to bring you flowers.”

— Jorge Luis Borges

A gardening guide for your mind

First, you need to seed your mind garden with quality content. The format may impact how close you are to the source. For instance, reading a research paper will probably give you deeper insights into a specific scientific process and the methods behind the team’s findings, whereas reading a book about a broader topic will give you lots of superficial nuggets of information.

The depth of the content you consume is not a measure of quality. Reading broad content is also a way to plant many seeds, which you may decide to nurture or not in the future. On the other side of the spectrum, some papers published in peer-reviewed publications don’t stand up to scrutiny (fraud accounts for 60% of retraction of published papers). Having a diverse information diet is more important than striving for an unattainably perfect information diet.

When consuming content, grow branches on your knowledge tree by taking notes. Short notes, long notes—it doesn’t matter as much as writing your thoughts in your own words. That’s called the generation effect, and it states that you better remember information when you create your own version of it.

Over time, you will find yourself going back to certain corners of your mind garden more often than others, and that’s alright. That’s you developing your unique perspective and own gardening expertise.

A mind garden is not a mind backyard. It’s not about dumping notes in there and forgetting about them. To tend to your garden, you need to plant new ideas. The best way to do this is by replanting stems and cuttings from existing ideas you’ve added to your garden—by consistently taking notes, and combining them together, a bit like grafting (Conor White-Sullivan, the founder of Roam, calls this idea sex). Sometimes, two seemingly remote or even incompatible ideas will give birth to a new insight. (look at the pomato, a weird hybrid of tomato and potato)

When you find some of these new combinations particularly interesting, share the seeds with fellow gardeners. Leverage the knowledge of other mind explorers. Keeping a digital garden where you can have a shareable copy of your ideas is a great way to contribute to the growth of our collective intelligence.

Creating a digital garden

While the notion of a mind garden may seem conceptual, it can manifest in very practical ways. The best demonstrations of well-tended mind gardens I have recently seen were all digital gardens of some sort. Here are some of my favourite:

- Andy Matuschak’s working notes. A thinking environment featuring evergreen notes with a unique navigation system, where you can compare notes side by side and explore various sub-links in an organic way. As you will see later in this article, my own digital garden was heavily inspired by Andy’s.

- Tom Critchlow’s wikifolder. Tom seems to have coined the term “digital garden”—his related concepts of streams (Twitter), campfires (blog), and gardens (personal wiki) are very interesting.

- Joel Hooks’ digital garden. A great blog post explaining the philosophy behind Joel’s blog, inspired by Tom Critchlow’s principles: a place to post “ideas, snippets, resources, thoughts, collections.”

- Gwern Branwen’s website. Incredibly unique, this digital garden features completion, certainty, and importance levels of each article, a change log with the latest updates, and link previews on hover. (also, dark mode)

- Meaningness by David Chapman. More of a book that’s being written publicly than a simple digital garden, this website features lots of interesting ways to connect the dots as well, with link previews, glossary explanation on hover for important words, and work-in-progress pages.

Maggie Appleton collated a list of digital gardens which I encourage you to explore. Many interesting examples which may be a reflection of the many ways our minds work.

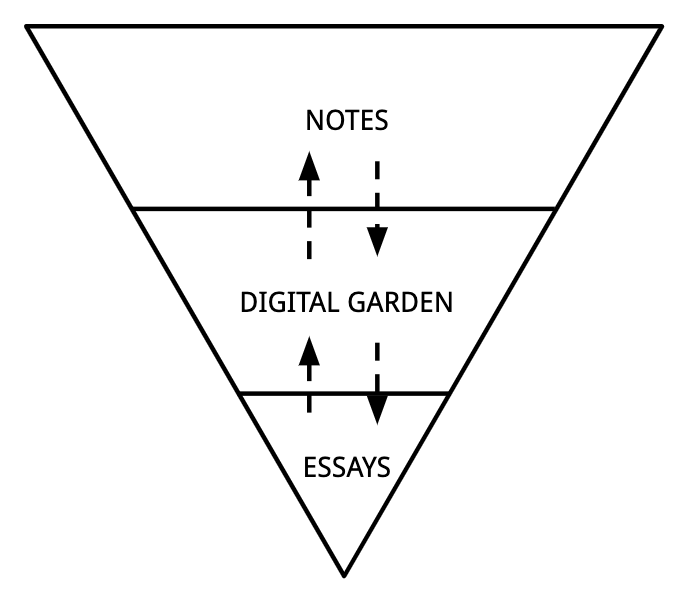

As I mentioned, I recently decided to create my own digital garden as an experiment. You can have a play with it here. Having several places to publish content may seem confusing, but it’s fairly simple:

- Your note-taking app, such as Roam or one of its open source alternatives for instance, can be used for collating snippets, ideas, and raw thinking. Use it to seed your garden and connect the dots.

- Once you have managed to articulate a new idea (new to you at least), write down a few more structured sentences, and add it to your digital garden as an evergreen note.

- You can stop here, but for people who have a proper blog or a newsletter, you may want to publish longer essays there.

Ultimately, the goal is to make sure all the information you consume (your input) can lead to increased productivity and creativity (your output) instead of festering and getting forgotten in your mind backyard. If you end up creating your own digital garden or just an analog version of your mind garden, please let me know.

P.S. Want to create your own digital garden? Check out this article with options that work whether you know are to code or not. I also run a small Telegram group for digital gardeners.