When I was in school, a friend of mine was offered the opportunity to coach the newly formed volleyball team. He didn’t think he had what it took to do a good job, but there was no one else better qualified, so he accepted. While they trained several times a week, my friend kept on telling other students how they didn’t stand a chance in the next tournament. The team was new and inexperienced, he said. Guess what happened?

No, not a miracle. They lost the tournament. I think they finished second-to-last. My friend had been so adamant about the team losing that he transferred that expectation to all the team members. Because they thought they would lose, they lost. My friend created a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The power of expectations

In 1965, a Harvard psychologist called Robert Rosenthal administered an IQ test to all students in a single California elementary school. While the exact scores were not disclosed to the teachers, they were told that about 20% of the students could be expected to be “intellectual bloomers”—with a better academic performance than expected in the following year. The names, which in reality had been chosen at random, were only communicated to the teachers.

One year later, the same IQ test was administered again. The 20% of students that were supposed to be “intellectual bloomers” did much better than their classmates. The difference was particularly significant with younger children in first and second grades. The effect discovered in Oak School Experiment study has become to be known as the “Pygmalion Effect”—the phenomenon where someone expecting something results in the prediction coming true.

“If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.”

The Thomas Theorem, as formulated in 1928 by William Isaac Thomas and Dorothy Swaine Thomas.

Also known as The Rosenthal Effect, it consistently shows that a teacher, manager, or supervisor’s high expectations of someone increase the person’s performance. What’s very interesting about the Pygmalion Effect is that it has been proven true even when the person with the expectations tries their best to hide them. That’s because we communicate a lot of what we think and feel through unspoken ways, such as body language and facial expressions.

To illustrate how powerful seemingly hidden expectations can be, let’s have a look at a famous story from the early twentieth century. William Von Osten, a mathematics teacher and horse trainer, managed to teach a horse how to perform arithmetic. The horse, named Clever Hans, would solve calculations such as adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing and share the result by tapping his hoof a certain number of times. Questions could be asked both orally and in written form. And Clever Hans was right 90% of the time. The animal understandably became a sensation.

In 1907, psychologist Oskar Pfungst decided to investigate the extraordinary phenomenon. What he found was that when placed behind a curtain so he couldn’t see the spectators, or when wearing blinders, or when the questionnaire did not know the answer to the question, the horse could not manage to perform the calculations correctly anymore. The horse had never been counting; he had been reading cues from the audience to determine when to stop tapping his hoof. The more excited people looked, the close he could guess he was getting to the right answer.

If a horse can read human body language this easily, you can imagine how well we can pick up these cues amongst ourselves. By merely thinking that someone will perform well, you can increase their performance.

And it works the other way around. The counterpart of the Pygmalion Effect is called the Golem Effect. Studies show that supervisors with negative expectations will produce behaviours that impair the performance of their subordinates and make the subordinates themselves produce negative behaviours. This is why checking your assumptions is important in order to avoid creating negative feedback loops.

Designing positive feedback loops

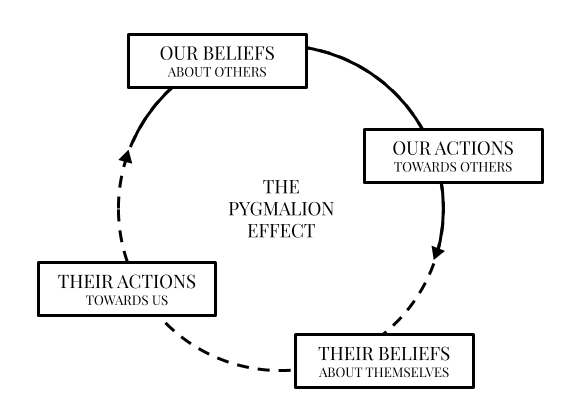

Whether you are a manager, a parent, a teacher, or have any position of influence and authority on others, being aware of the Pygmalion Effect—and its counterpart, the Golem Effect—is essential if you want to have a positive impact on their performance. Our beliefs about others influence our actions towards them, which impact their beliefs about themselves and their actions towards us, reinforcing our beliefs.

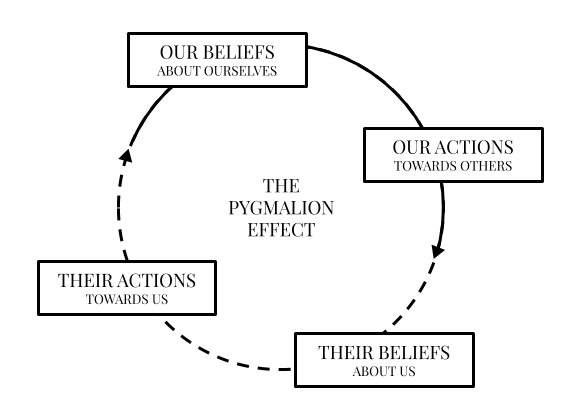

But the Pygmalion Effect also applies to your personal growth. Your beliefs about yourself impact your actions towards others, which influence their beliefs about you and their actions towards you. For instance, if you believe you are a hard worker, you will work hard, and people will think you are a hard worker and treat you as such.

In order to design positive feedback loops and nudge yourself and others towards success, you need to examine your beliefs and expectations.

- Be mindful of your expectations of others. Take some time to think about your beliefs and expectations of people around you—family, friends, colleagues. When you find negative expectations, try to reframe them in a more positive light. It’s not an easy exercise and it requires kindness and an open mind, but it can have a great impact on people’s self-expectations and thus performance.

- Question your internal beliefs. Now, turn to your beliefs about yourself. How do you expect yourself to perform? Identify any negative expectations and work on reframing them as well. Take your time, and be honest and kind with yourself.

- Develop a growth mindset. Coined by Carol Dweck, a professor of psychology at Stanford University, a growth mindset—as opposed to a fixed mindset—is when you believe you can accomplish anything with enough hard work. You don’t see your abilities and skills as fixed, and you see obstacles as challenges on the path to growth.

These sound like three simple steps, but they require a high level of introspection and honesty. Taking these steps will result in subtle changes that may not be visible at first, but simple being aware of the Pygmalion Effect can help you design positive feedback loops and write the self-fulfilling prophecy you want to see happen. It’s a way to gently push for the outcomes you wish for, both for yourself and for others.