In many cultures, freedom and autonomy are considered critical to our well-being. Having the ability to do what we want, when we want, and to explore our options seem like healthy attitudes. This is why supermarkets are filled with so many variations of similar products.

We think that the more choices we have, the better off we are. But the relationship between choice and psychological well-being is not as straightforward. Having too many options can be overwhelming. The many potential outcomes that may result from making the wrong decision result in overchoice.

“Autonomy and Freedom of choice are critical to our well being, and choice is critical to freedom and autonomy. Nonetheless, though modern Americans have more choice than any group of people ever has before, and thus, presumably, more freedom and autonomy, we don’t seem to be benefiting from it psychologically.”

Barry Schwartz, Psychologist.

Too much information

Named after British and American psychologists William Edmund Hick and Ray Hyman, the Hick–Hyman law describes the time it takes for a person to make a decision as a result of the possible choices they have. It states that increasing the number of choices will logarithmically increase the decision time. For example, research shows that when looking for an option in an alphabetical menu, people will take longer to select a particular command if the list is longer.

Making a decision involves knowing what you want, understanding what options are available, and then making trade-offs between the available options. It makes sense that the more information we have, the longer it takes to scan it, consider it, ponder it—thus prolonging the decision time. Picking between two options is indeed quicker than picking between ten options.

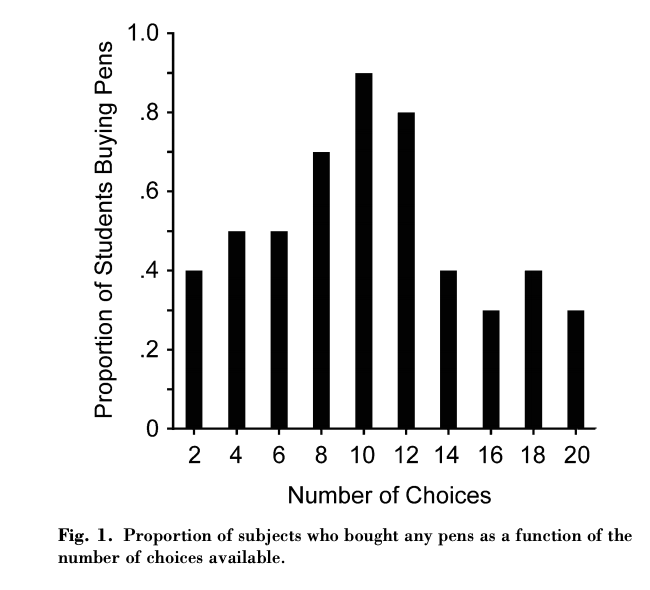

But what’s interesting is that overchoice does not only impact decision time. Having too many options is not only bad for decision making, it’s bad for our mental well-being. Many studies have documented overchoice, and found that it leads people to delay or completely opt-out of decision-making, report lower choice satisfaction, and make poorer decisions when they are faced with a large number of options.

Overchoice or choice overload

Making a choice can be seen as a battle between freedom and commitment. While we are exploring options, we’re free to pick any. We feel autonomy. But, once we make a choice, we are committing to an option, and therefore closing the door to the other ones. This may mean having to make trade-offs or missing opportunities. Having too many choices makes this battle between freedom and commitment even more complex.

The term “choice overload” was coined by Alvin Toffler in 1970. It occurs when people are in a situation where many equivalent choices are available to them. Research found that the satisfaction of choices by number of options available follows an inverted U model—in other words, there is a sweet spot with not too few, and not too many options—just enough to maximise our perception of freedom and our mental well-being.

If we have too few options, we feel frustrated. Too many, and we may experience analysis paralysis, fear of a better option, and even regrets afterwards. Did we really make the right choice? Wasn’t another option better than the one we picked?

Unfortunately, it is very rare that we have complete control over the number of options presented to us. But the good news is: there are ways to manage overchoice.

How to overcome the paradox of choice

In his book The Paradox of Choice, Barry Schwartz designed in six-step method to make good choices when faced with overchoice.

- Figure out your goal. Before even starting to consider the options, ask yourself: “What do I want?” We often rush into analysis mode, when we should really take a step back and consider our goal—what we expect to get out of this choice. This is called expected utility. The idea of this six-step process is to align your expected utility with your remembered utility—what you will actually get from making a particular choice.

- Evaluate the importance of your goal. We often make rules of thumb based on anecdotal evidence, without taking the time to really think about what we want to achieve. Before making a choice, stop for a second to ask yourself if your perceived goal is in line with what you actually want.

- Frame the options. Instead of looking at the options in a vacuum, group them together so they are easier to evaluate. For example, if you are looking at potential options for a Friday night dinner, you could frame them by types of food, or eating-out or eating-in.

- Evaluate the options. Now, you can finally evaluate how likely each of the options is to meet your goal—your actual goal which you have determined in step 2, not necessarily the first one that came to mind in step 1. Be as honest as you can with yourself.

- Pick the winning option. The only wrong choice you can make is to not choose. Based on your goal, your framing, and your evaluation, pick an option and go with it. It doesn’t mean that if you’re looking at different shoes to buy you should necessarily buy a pair. Not buying a new pair of shoes is also a valid option.

- Revisit your goal. Based on your experience, go back to step 1 and 2 and evaluate whether your decision resulted in the outcome you expected—the expected utility. If that wasn’t the case despite going through all of these steps, chances are you didn’t define the right goal in the first place.

We don’t always have control over how many options we are presented with, but we do have control over how we react and control our decision-making process. While experiencing overchoice can be overwhelming, it is manageable when using a more structured approach to decision-making.