Fake news has become a hot topic. But the deliberate disinformation of the general public via traditional outlets or social media goes beyond the news: there is also an alarming rise in “fake science.” The brain and the mind feel extremely familiar. We do spend lots of our time inside our heads. That’s why it’s easy to disseminate false—but great sounding—information about the brain. This is what a neuromyth is: an erroneous belief about how the brain works that is held by a large number of people. Let’s explore a few of them.

5 popular beliefs about the brain that are actually neuromyths

Neuroscience is pretty young—neuroimaging technologies have only been developed over the last twenty years. As a result, it’s an ever-evolving field and it’s pretty hard to separate fact from fiction. Here are a few of the most common neuromyths, how they came about, and why they’re wrong.

- We only use 10% of our brain. This neuromyth was the basis of at least two sci-fi films: Neil Burger’s Limitless, starring Bradley Cooper and Luc Besson’s Lucy, starring Scarlett Johansson. The poster for Lucy doesn’t shy away from this incorrect belief: “The average person uses 10% of their brain capacity,” it says. People love this myth because it makes them feel good. It means that you may have some huge amount of untapped potential which could unlock should you use the right techniques or tools. Marketers also love this myth because it helps them sell dubious products that are supposed to let you access the remaining 90% of your brain capacity. First, there’s lots of evidence showing that whatever an individual is doing—even if they’re told to just lay down in the scanner and not do anything—pretty much all of the areas of the brain are active. Second, it makes no evolutionary sense to have an organ that is 90% unused. Especially when it comes to the brain, which uses a staggering 20% of the body’s energy, despite being only 2% of its weight. The myth probably comes from William James, widely considered as the father of psychology, who wrote that it’s unlikely most people would ever reach 10% of their potential. Somehow, this became 10% of their brain.

- We’re either right-brained or left-brained. Every day, there are businesses paying for workshops teaching their employees that they’re either right-brained (artistic expression and creativity) or left-brained (logical thoughts and calculations). I don’t have a reference to back this up and it may not be true, but it is a fact that many people do believe this and there are lots of books being sold that promote this very incorrect idea. But imaging studies show that both parts of the brain are active when people are engaged in creative tasks. There is absolutely no reason to think that certain forms of thinking—say creative versus rational thinking—are localised in a specific hemisphere of the brain. Want to have a good laugh? There’s an article on WikiHow telling you to “breathe through your left nostril to activate your brain’s right side” to exercise the right side of your brain. At least they admit that “it’s not supported by rigorous science.”

- We have multiple intelligences. The Harvard psychologist Howard Gardner came up with the theory of multiple intelligences in the 1980s— and I say “came up with” because there wasn’t any actual data involved with this theory: it was just Gardner’s opinion that there are multiple intelligences with variable levels among people. He started with a list of seven “intelligences”—musical-rhythmic, visual-spatial, verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, and intrapersonal. But because it wasn’t enough, he then added a few more (still without any data to back his claims): naturalistic, existential, and moral intelligence; he even suggested cooking intelligence and sexual intelligence as potential candidates. First, what Gardner calls intelligence could simply be called skills. Second, research shows that our skills are not broadly independent from one another. People who tend to do well on one type of test tend to do well in them all. That’s called “general intelligence” and it has way more tangible evidence to support it than the theory of multiple intelligences. (quick note that the book Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences by Gardner has nothing to do with my own mindframing method for mindful productivity)

- IQ tests just tell you how good you are at doing IQ tests. This was one of the most surprising ones for me, because I did believe in this neuromyth before writing this article. And it’s actually a lecture at King’s College debunking this myth that prompted me to write this article. According to my lecturer (the amazing Dr Stuart Ritchie), while IQ tests are certainly flawed in all sorts of ways, they are some of the most reliable and predictive tests that exist in the whole of psychological science. A study with almost a million men who did an IQ test as part of their military service in Sweden showed that the higher the IQ, the longer they lived. I will write a whole article about this, but many studies have shown that IQ tests do predict mortality, as well as educational attainment, work success, physical and mental health, and many other things. The myth that IQ tests only tell you how good you are at IQ tests has been pretty much debunked.

- People have different learning styles. I already mentioned this neuromyth in my article about learning how to learn. But it’s worth mentioning again because it’s also a pretty popular neuromyth. The learning style theory states that people differ in the way they learn, which is due to some innate property of their brains and that teaching should be customised to their particular learning style. According to that theory, some people have more of a visual learning style, others an auditory learning style, etc. It sounds elegant, but it’s completely wrong. Research shows that changing the teaching method has no impact on students success based on their preferred learning style. In short, we do have a preferred learning style—one that feels more comfortable—but using another one has no impact on our performance. We don’t have different learning styles, we just have different learning preferences.

There are many, many other neuromyths—and I may write a follow-up article. But what’s crazy is that it’s not only the general public that believes them.

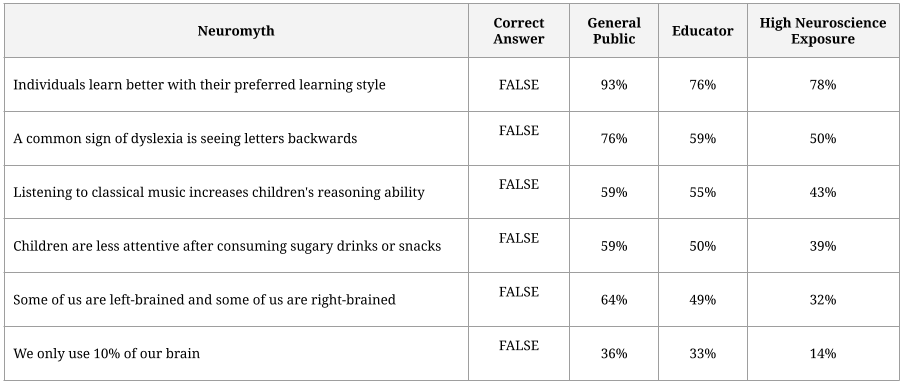

The table above was adapted from a scientific paper about neuromyths. The first column lists common neuromyths. The researchers then asked people to state whether these were true or false. People were put into three groups: the general public, educators (such as teachers), and people with high neuroscience exposure—think scientists and doctors. You can see the percentage of them for each group that believed these neuromyths to be true. For example, 59% of the general public, 55% of educators, and 43% of individuals with high neuroscience exposure believe in The Mozart Effect, a theory which suggests that listening to classical music can boost our intelligence. Which is false.

Even more depressingly, 14% of people with high neuroscience exposure believe that we only use 10% of our brain. Overall, the research found that on average 46% of the most educated people when it comes to the brain believed in these neuromyths.

The worst thing? Research shows that more education may not be able to fix this. Taking an educational psychology course does improve general knowledge of neuroscience but does not reduce belief in neuromyths. Neuromyths really do seem to be sticky. They feed into our desire to believe that everyone can be good at something, that we have untapped potential, that we are unique.

While it has been shown that it’s incredibly hard to change people’s mind when it comes to neuromyths, I hope this article will be a small contribution that may educate individuals who are willing to abandon some strongly-held beliefs about the way their brain works.