“I am not a writer. I’ve been fooling myself and other people.”

John Steinbeck, very talented and successful author who won the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Yesterday, I launched my newsletter on Product Hunt. The launch went incredibly well, with 1,300 new subscribers joining the list, lots of kind comments, and a second spot in the daily rankings. But today, when I woke up, I felt weirdly anxious. In a few days, I’ll need to send my weekly newsletter to all of these new people who gave me their precious email address. What if they’re disappointed in the content? What if they regret subscribing? What if they think I’m not a good writer?

I felt something similar when I was working at Google. Surely, someone would sooner or later discover that I didn’t belong there. Everyone around me sounded smarter, more on top of things. But, one day, I discovered an internal Google+ group (yes, it was a long time ago) called “The Impostors Group.” In it, lots of anonymous posts by fellow colleagues about their fear of being exposed as a fraud and fired from the company. It was somehow a relief to find out that I wasn’t the only one.

Impostor syndrome is real and has been well documented. It’s a psychological pattern in which people doubt their accomplishments. Despite external evidence of their competence, people experiencing impostor syndrome will remain convinced that they do not deserve their success, attributing it to luck or thinking that they have somehow deceived others into thinking that they are more intelligent than they actually are.

The 5 types of impostor syndrome

While most of the early studies around impostor syndrome have been focused on high-achieving women, research shows that it can affect both men and women equally. The term impostor syndrome was coined by Dr. Pauline Clance and Dr. Suzanne Imes in 1978, which they defined as an individual experience of self-perceived intellectual phoniness.

Dr Valerie Young, who is today considered the leading expert on the impostor syndrome, has identified five main categories of self-defined impostors:

- The perfectionist. Many people who suffer from impostor syndrome are perfectionists. Perfectionists set excessively high goals for themselves. When they fail to reach their goals, they experience unhealthy self-doubt. If you’re often dissatisfied with your performance and ruminate about how you could have done things better, your perfectionism may result in experiencing impostor syndrome.

- The natural genius. These people were often told that they were smart from a very young age. They’re used to performing well relatively easily. Because of this, they also set their internal bar for success incredibly high. And when they’re not able to do something quickly and easily, they become anxious. In a demanding environment with complex and challenging work, people who fall under the natural genius category are prone to experiencing impostor syndrome.

- The soloist. While being independent can be a good thing, soloists take it a step too far. They see asking for help as a weakness, and try to do everything on their own. They fear that asking a question to a colleague may reveal the fact that their not up to par with the job. If you struggle to ask for help and try to do everything on your own, you may be a soloist suffering from the impostor syndrome.

- The super(wo)man. People in this category will tend to work harder than everyone else in an attempt to hide what they believe is a lower level of competence. They will work longer hours without telling their colleagues about it, accept any project that comes their way, struggle during downtime, and often sacrifice their hobbies to get more done at work.

- The expert. Finally, the experts are people who measure their competence based on how much they know. Experts believe that they don’t know enough—and that they will never know enough—and fear being exposed as unknowledgeable or inexperienced. Some may constantly be seeking out trainings or certifications to compensate for their perceived lack of knowledge, or try to gather as much information as possible when starting a project, which can lead to procrastination.

As you can imagine, many of the behaviours showcased in these five categories can lead to burnout. The constant worry that comes with the impostor syndrome often takes a toll on people’s mental health. And it doesn’t help that for most people who suffer from this phenomenon, secrecy is the rule. After all, the impostor syndrome is all about not being found out. Luckily, there are ways to deal with it.

How to deal with impostor syndrome

There’s no magic bullet to beat impostor syndrome, but there are a few strategies you can apply to better manage the anxiety and start accepting that nobody made a mistake, and you belong to the group of smart and talented people you get to work with.

- See yourself as a work in progress. Learning and skill-building takes time and are a trial-and-error process. Accept that growing as a person involves making mistakes. If you’re not making mistakes, you’re probably stagnating. Which is probably worse in the long term than your colleagues somehow realising that you shouldn’t be there.

- Practice just-in-time learning. Instead of trying to be an expert on everything and hoarding knowledge for false comfort, acquire relevant skills when needed for specific tasks. This will be much more productive, and much more manageable.

- Realise that there’s no shame in asking for help. If you don’t know how to do something or struggle to solve a problem, ask a coworking. Asking good questions is actually a great skill to have, but it takes practice.

- Practice internal validation. Nobody should have more power to make you feel good about yourself than you. Instead of seeking external validation, nurture your inner confidence with positive affirmations. Yes, it can feel cheesy to talk to yourself, but research shows that these kind of self-affirmations activate the brain systems associated with reward, as well as decrease stress, increase well being, improve performance and make people more open to behaviour change. Nothing to lose in giving it a try!

- Celebrate your achievements. Everytime you reach a milestone, take the time to celebrate your hard work. It’s great to be a forward thinker and of course there’s no need to spend too much time thinking about the past, but give yourself a pat on the back before moving onto the next goal.

- Fail like a scientist. Finally, see failure as part of a bigger experiment which is your life. Scientists often have to repeat experiments thousands of times to get a conclusive answer. And more often than not, the answer they get is that their initial hypothesis is wrong. Not performing the experiment would have allowed them to stay in a cozy limbo of being not wrong, but is that what a scientist would prefer? Apply this principle to cultivate your curiosity and reduce your fear of failure.

Impostor syndrome can come and go depending on the job, the people you work with, and your current mental state. Recognising the signs and making a conscious effort to fight the symptoms are the first steps in dealing with it.

Real impostors don’t suffer from impostor syndrome

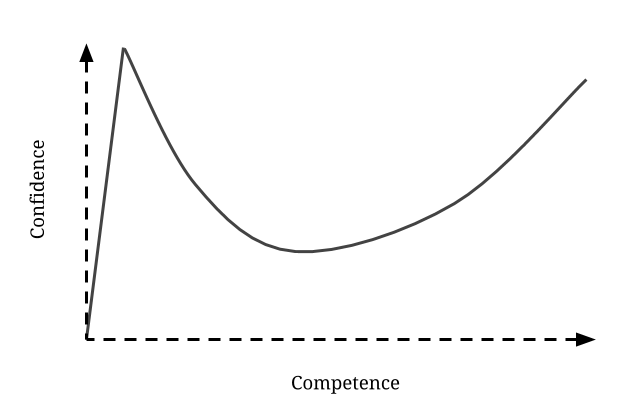

Finally, something that’s good to be aware of is that people who don’t have imposter syndrome might have reason to question their competence. This is due to the Dunning-Kruger effect, a cognitive bias in which people mistakenly assess their cognitive ability as greater than it is. It’s basically being ignorant of your own ignorance.

“In short, those who are incompetent, for lack of a better term, should have little insight into their incompetence—an assertion that has come to be known as the Dunning–Kruger effect.”

David Dunning, Social Psychologist & Professor of Psychology.

There is evidence suggesting that imposter syndrome correlates with success and that high levels of self-confidence may not correlate with actual abilities.

“They don’t feel at all like frauds—they feel they know exactly what they’re doing and how could other people not know what they’re doing. But it turns out, they don’t know enough to know how little they know.”

Jessica Collett, Professor of Sociology.

Some famous people who have reportedly experienced impostor syndrome include Michelle Obama, Neil Amstrong, Tom Hanks, and Emma Watson (each link is to the interview in which their share their experience with the phenomenon). So if you are battling with impostor syndrome, at least tell yourself that you’re in good company.