When you want to learn or build something new, it’s tempting to just get going. Read as much as you can, do some tutorials, work on some related projects. Short-term, this gives you a motivation boost. You feel like you’re moving forward. But, after a while, you notice that you’re not progressing as fast as you expected. You may even start burning out. Turns out, cramming content inside your brain is not the most effective way to grow. Instead, you need to develop your metacognition.

What is metacognition?

The word “metacognition” literally means “above cognition” — it’s one of the most powerful forms of self-monitoring and self-regulation. It’s a fancy word for something fairly simple once you break it down.

Put simply, metacognition is “thinking about thinking” or “knowing about knowing.” It’s being aware of your own awareness so you can determine the best strategies for learning and problem-solving, as well as when to apply them.

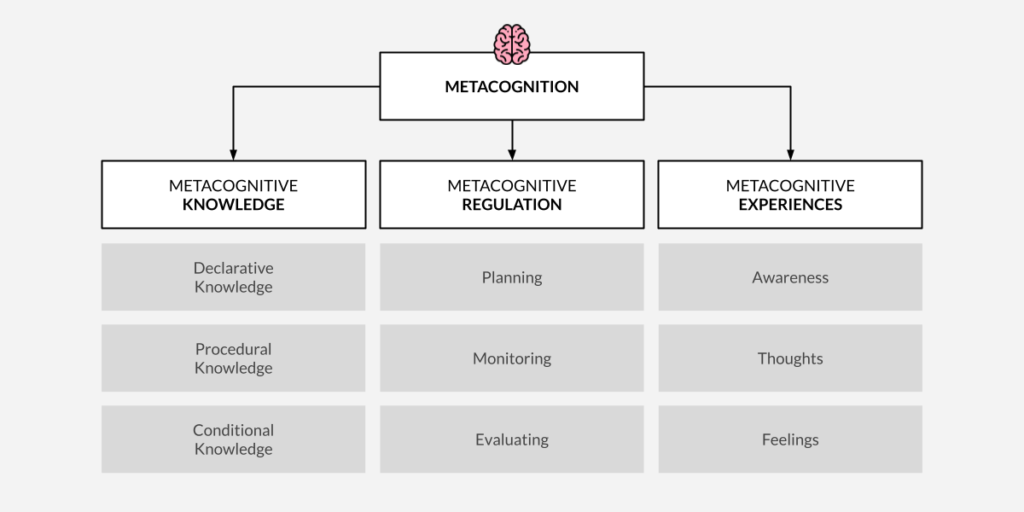

Researchers have identified three main components that make up metacognition. These are not clear, separate aspects, but rather interact together in complex ways to influence the way you learn, create, and solve problems.

- Metacognitive knowledge. What you know about yourself and others in terms of thinking, problem-solving, and learning processes.

- Metacognitive regulation. The activities and strategies you use to control your thinking.

- Metacognitive experiences. The thoughts and feelings you have while learning something new or trying to solve a problem.

Metacognitive knowledge in particular can be divided into three further categories. The first is declarative knowledge — the knowledge you have about yourself as a learner and about what factors can influence your performance. The more you know about yourself, the higher your metacognitive knowledge will be.

The second is procedural knowledge — what you know about learning in general, such as learning strategies you read about or that you have applied in the past. The more you learn about learning, the more procedural knowledge you will have.

Finally, conditional knowledge refers to knowing when and why you should use declarative and procedural knowledge, allocating your mental resources in a smart way to learn better. The more mental models you have in your toolbox, the more you will develop your conditional knowledge.

Even if you don’t remember all those details, just know that metacognition is understanding your thought processes and emotions and the patterns behind them. It’s the highest level of mentalisation — an ability that is part of what makes us human.

The benefits of metacognition

Metacognition can help you maximize your potential to think, learn, and create, all while taking care of your mental health. Beyond the elevated self-awareness and consciousness you’ll experience by applying metacognitive strategies, scientists have investigated some of the many benefits of metacognition.

- Learn better. Research shows that high-metacognition learners identify challenges much faster and change their tools and strategies to better achieve their learning goals. Metacognition can even compensate for IQ and lack of prior knowledge when it comes to solving new problems.

- Make decisions faster. Monitoring and controlling your ongoing cognitive activity can make you aware of your cognitive biases and help avoid mistakes, or at least not reproduce the same mistakes twice. In addition, because of heightened awareness, metacognition leads to a reduction in response time, which reduces the time to solve a problem or complete a task.

- Be more creative. According to Dr Markus Lång, all narrative works of art can be defined as metacognitive artifacts which are designed by the creator to anticipate and regulate the cognitive processes of the recipient. Intrinsically speaking, creativity is thinking about thinking.

- Improve your mental health. Metacognition gives you the ability to understand your mental health and to adapt your strategies to cope with the source of any distress. As such, researchers defined metacognition as the process that “reinforces one’s subjective sense of being a self and allows for becoming aware that some of one’s thoughts and feelings are symptoms of an illness.”

As you can see, metacognition really is the mind’s Swiss Army knife. That one ability can help you learn better, make decisions faster, be more creative, and improve your mental health. So, how can you experience those benefits?

The ingredients of metacognition

Metacognition has many components, but it doesn’t mean that it has to be complicated to apply. According to scientists, there are only three skills you need to master in order to improve your metacognition.

- Planning. Before you start learning something, tackling a new problem, or exploring a creative idea, think about the appropriate strategies you will use, as well as how you will allocate your time and energy. This phase is based on your metacognitive knowledge — of yourself (declarative knowledge), learning strategies (procedural knowledge), and when to use them to maximise your performance (conditional knowledge).

- Monitoring. While learning, solving a problem, or working on a creative project, stay aware of your progress. Are you struggling with certain aspects in particular? Are there other elements that seem to be a breeze to go through? Instead of passively experiencing your thoughts and feelings, ask yourself these questions to see what works and what doesn’t.

- Evaluating. When you’re done with a chunk of work, consider how well you performed and re-evaluate the strategies you used. Make any necessary changes before starting to work on the next part of your project.

As these may feel quite abstract, let’s have a look at some simple strategies you can use to put these principles into practice.

How to develop your metacognition

“Thinking about thinking” sounds great in theory, and there’s lots of research demonstrating its many benefits. But what does it look like in practical terms? Here are some activities you can experiment with to develop your metacognition.

- Keep a learning journal. If you already keep a journal, you can add a section at the end of each day answering a few questions about what you’ve learned, what went well, what didn’t, and what you want to learn next. Plus Minus Next journaling is a great approach to keep a learning journal, or you can have more of a free-flow approach — whatever feels most comfortable. The goal is to be aware of your progress, the challenges you face, and the strategies you will apply to improve your thinking, learning, and decision-making.

- Think aloud. While mind wandering can contribute to creativity, it can also be unproductive when not paired with a phase of focused thinking. Thinking out loud may feel a bit strange, but it will help you stay on track when practicing metacognition. Another way to think out loud is to find a thinking buddy — someone you meet with regularly to discuss your progress and challenges, and to suggest metacognitive strategies to each other. You can then take notes about the discussion in your learning journal.

- Apply mental models. Mental models are frameworks that give us a representation of how the world works, a set of beliefs and ideas that we form based on our experiences that guide our thoughts and behaviors and help us understand life. For example, knowing about the availability heuristic helps you think about human relationships. Knowing about temporal discounting helps you pay attention to the consequences of your decisions, even if they are far in the future. Building your own toolbox of mental models is a productive way to practice metacognition.

- Use a tool for thought. After a while, you will start accumulating a collection of metacognitive strategies based on mental models and knowledge about yourself. To make the most of these strategies, it can be helpful to use a tool for thought so you can easily store and retrieve them based on the challenge at hand. For instance, you could tag your metacognitive strategies depending on whether they are more relevant for learning or problem-solving, or if they are more useful to deal with procrastination or creative anxiety.

In his treatise On the Soul, Aristotle (384–322 BC) wrote: “What thinks and what is thought are identical.” Thinking is combining your existing knowledge into new ideas. Metacognition is the act of observing and reflecting on our thoughts. It’s the mind’s Swiss Army knife: when practiced regularly, it can make you a better learner, decision-maker, and creator, all while supporting your mental health.