I have been meaning to write about procrastination for a while, but… Well, I procrastinated. We procrastinate when we delay or postpone the stuff we should be doing. Procrastination is incredibly common and something we have all struggled with at one point or another.

Some people procrastinate out of fear of being judged for their work, so they just avoid completing the task. Others are thrill-seekers that claim to enjoy the rush that comes with racing to meet a deadline.

It’s a universal challenge, which bears the question: what is it about the human mind that drives us to put off tasks are actually quite important to us?

A little history of procrastination

Humans have always struggled with procrastination. The problem goes back at least as far as Ancient Greece. In Plato’s Protagoras, Socrates asks how it is possible that, if one judges an action to be the best, one would do anything other than this action.

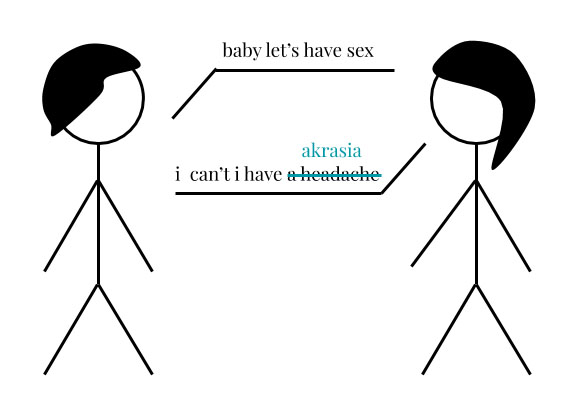

Aristotle used the word akrasia—or “weakness of will”—to describe this state of acting against one’s better judgment. The term was later used several times in the Bible and described as a “sin of the mind.” Paul the Apostle even warns husbands and wives to not fall prey to akrasia as a reason to deprive each other of sex!

When we get stuck into an akratic loop, we know we “should” do something, but we resist doing it. The sister word “procrastination” itself comes from the latin “pro”, which means “forward”, and “crastinatus”, which means “till next day.”

Procrastination makes it difficult and stressful to finish certain tasks or to meet deadlines, so why do we do this to ourselves?

The science behind procrastination

Many people think that procrastination is due to lazy habits or just plain incompetence, but it couldn’t be further from the truth. Procrastination actually finds its roots in our biology. It’s the result of a constant battle in our brain between the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex.

The limbic system, also called the paleomammalian brain, is one of the oldest and most dominant portions of the brain. Its processes are mostly automatic. When you feel like your whole body is telling you to flee from an unpleasant situation, it’s your limbic system talking. It’s also tightly connected to the prefrontal cortex.

The prefrontal cortex is newer, less developed, and as a result somewhat weaker portion of the brain. This is the part of your brain where planning complex behaviours, expressing your personality, and making decisions happen. The prefrontal cortex is “the part of the brain that really separates humans from animals, who are just controlled by stimulus,” explains Dr Tim Pychyl, a psychology professor and the author of The Procrastinator’s Digest: A Concise Guide to Solving the Procrastination Puzzle.

Because the limbic system is much stronger, it very often wins the battle, leading to procrastination. We give our brain what feels good now. In fact, procrastination can also be seen as the result of a battle between your present self and your future self.

“We have a brain that is selected for preferring immediate reward. Procrastination is the present self saying I would rather feel good now. So we delay engagement even though it’s going to bite us on the butt.”

Dr Tim Pychyl, Author & Psychologist.

And the later biting on the butt exactly the problem. Procrastination can be extremely harmful, not only on a professional level, but also on an emotional level.

You have probably heard someone claim this at least once: “I know I procrastinate, but it’s fine, I perform better under pressure.” But that feeling of performing better under pressure is likely to be an illusion.

A study conducted by Dr Dianne Tice and Dr Roy Baumeister tracked the performance, stress, and overall health of a group of college students throughout the semester. While the procrastinators originally displayed lower levels of stress, at the end of the semester, not only were they more stressed, but they also earned lower grades. So much for performing better under pressure.

How to be kind to your future self

While it’s great to better understand the science behind procrastination — and to stop blaming yourself — it would be even better to give our prefrontal cortex a little help in fighting the good fight against our lazy, self-indulgent limbic system.

And there’s some good news: because it doesn’t arise from a fixed structure in the brain, we can actually overcome procrastination. Here are five simple tricks you can start experimenting with today.

- Do the worst thing first. Putting off dreaded tasks will sap your mental energy, while checking it off your list will make you feel more productive.

- Create smaller chunks. Make the job smaller by defining tasks that feel more manageable. Commit to only do the first one, and see how you feel afterwards.

- Try the 10-minute trick. Set a timer and commit to working on the task for just ten minutes. Work as hard as you can during that time.

- Work in public. Leverage the power of positive pressure by publicly committing to your goals. It can be as simple as telling a friend or posting a tweet.

- Give yourself a reward. Pick something self-indulging that would make you very happy as a carrot for your limbic system. That’s your gift to yourself should you work—even a little—one sub-item of the task you’ve been avoiding.

Another important factor is your environment. Design your workspace in a way that minimises distractions, whether physical or digital. This means putting your phone in another room while you work, only keeping the necessary tabs open in your browser, and marking yourself as offline in Slack.

If you’re at home, work from an uncluttered table. If you work from an office or a coworking space, consider investing in noise-cancelling headphones. They also work wonders at making it clear to your colleagues that you’d rather not be interrupted.

You can also implement “micro-costs” that require you to make a small effort in order to procrastinate, such as having to use a separate laptop for gaming. The additional delay could give enough time to your prefrontal cortex to kick-in and help you change course.

Research from Stockholm university tested these self-help strategies with a group of a group of 150 self-reported procrastinators and found a reduction in procrastination. If you suffer from chronic procrastination, though, there may be a bigger underlying problem worth looking at. “You might need therapy to better understand your emotions and how you’re coping with them through avoidance,” says Dr Tim Pychyl.

And while most scientists agree that procrastination can be beaten through retraining ourselves, building mental strength, and self-help techniques, don’t beat yourself up if you’re an occasional procrastinator. Now you know it’s perfectly natural and rooted in our biology.