Most people want to be happy. In other words, the majority of human beings are engaged — consciously or unconsciously — in actions designed to improve their levels of happiness.

Despite our best efforts, these actions can sometimes have the opposite effect. For example, chasing a promotion at work only to realize we have become burned out in the process.

Other times, our actions can make us happy in the short term but unhappy in the long term. For example, earning a large sum of money only to realize later we have over-indexed on financial success at the expanse of our relationships.

These complexities are partly why there are many definitions of happiness, and the concept has changed so much over the centuries. Happiness can in fact be described as very different things depending on the time scale you consider:

- Short-term: your current feelings and emotions, such as pleasure, joy, or sadness. This is what you experience here and now.

- Medium-term: your subjective life satisfaction. In a study about how happiness differs across cultures, it was described as the “overall appreciation of one’s life as-a-whole.”

- Long-term: your conscious approach to thriving as a human being. Aristotle called it a life of “virtuous activity in accordance with reason.”

The first two are probably very familiar to you, so it’s the third vision of happiness — the long-term one — that we will explore in this article. Aristotle coined it eudaimonia in Greek, which is sometimes translated as “human flourishing”.

Aristotle’s philosophy was that, because reason (logos in Greek) is unique to human beings, the ideal goal of human life is the fullest exercise of one’s reason. According to Aristotle, it’s not enough to be skilled or talented in order to live a good life. To achieve happiness, we must be engaged in activities that are intellectually stimulating and that drive us to excellence.

But Aristotle did not dismiss other important dimensions in one’s life, such as friends, wealth, and power. In fact, he doubted that we could achieve eudaimonia if we were completely missing one of these crucial aspects. For example, he found it hard to imagine a happy life if you were missing “good birth, good children, and beauty.”

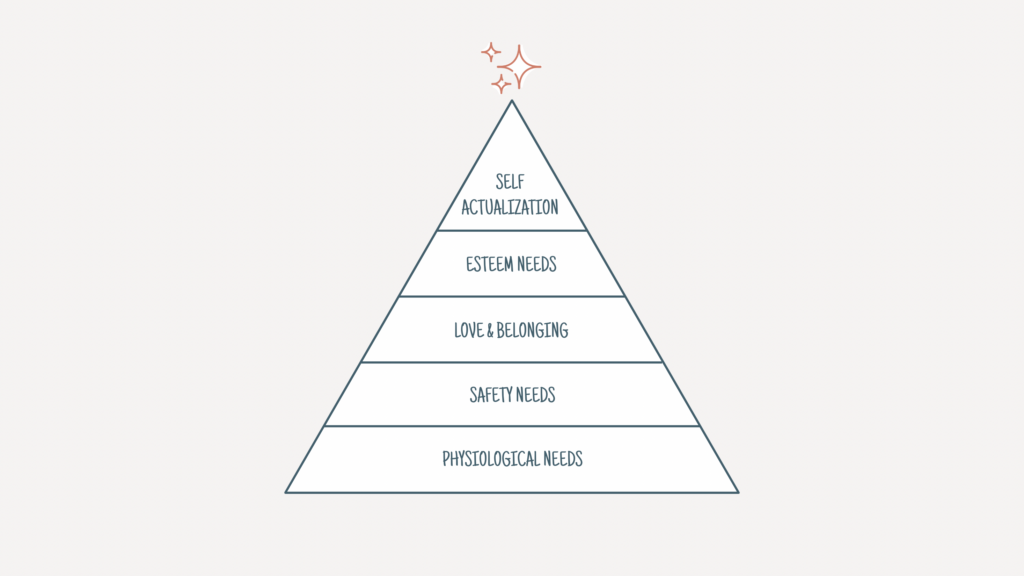

In more modern terms, it’s hard to conceive being happy if you’re without money and without friends. And this is exactly one of the most known theories of happiness in psychology, the pyramid of Maslow, is all about.

It’s an elegant theory, but Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs has been heavily contested. While research does seem to validate the existence of universal human needs, their ranking seems to wildly vary from one culture to another, and even from one individual to another.

So what are some alternative theories of happiness that better capture the diversity and complexity of the human psyche?

Theories of happiness in psychology

Measuring happiness is hard. First, is happiness objective or subjective? Is it about how you feel right now, or in general? Is it rational, or emotional?

Psychologists are still debating these questions. To highlight how important this field of research is, there is even a dedicated Journal of Happiness Studies.

But there are three main theories towards which many researchers are gravitating:

- Freedom of Choice Theory: according to research by Ronald Inglehart, a professor and scientist, the extent to which a society allows free choice has a major impact on people’s happiness. When their basic needs are met, their degree of happiness depends on how much free choice people have in how they live their lives.

- Self-Determination Theory: evidence suggests that the ability to make choices without external influence and interference is also an important factor to live a happy life. Intrinsic motivation and the willingness to grow — basically being self-motivated — can determine how happy you are.

- Positive Psychology Theory: finally, positive psychology considers that instead of trying to fix things when they get broken, we should spend more time improving our mental wellbeing in a more positive and proactive way. This theory is backed by solid research showing the beneficial impact of self-help interventions. I’ll talk a bit more about it later in this article.

While these theories offer solid guiding principles, it’s also worth noting that seeking happiness at all cost can also have adverse effects. For example, scientists found that failure to meet overly high expectations can leave you depressed.

And research shows that happiness is way less valued in Eastern cultures than Western ones. For example, harmony is ranked higher in many non-Western cultures when it comes to the most important goals to pursue in life.

It makes it worth asking ourselves: shouldn’t we accept and fully experience all of the range of our emotions, both positive and negative? Could we seek happiness in a more balanced way?

A balanced approach to happiness

Sometimes, life objectively sucks. And sometimes, things are fine, but for some reason we still don’t feel quite happy. This is why there’s more to happiness than comfort and managing our levels of happiness is an art in itself. I’m saying “art” and not “science”, because neuroscience has not made a lot of progress so far when it comes to understanding the biology of happiness.

This great paper was published a few years ago and gives an overview of the current state of affairs when it comes to the neuroscience of happiness. In short, we have made lots of discoveries around the hedonic aspects of happiness—what brings us pleasure.

We know what parts of the brain get activated when we feel pleasure, but the research trying to understand what happens in our brain when we’re happy and why is still highly speculative.

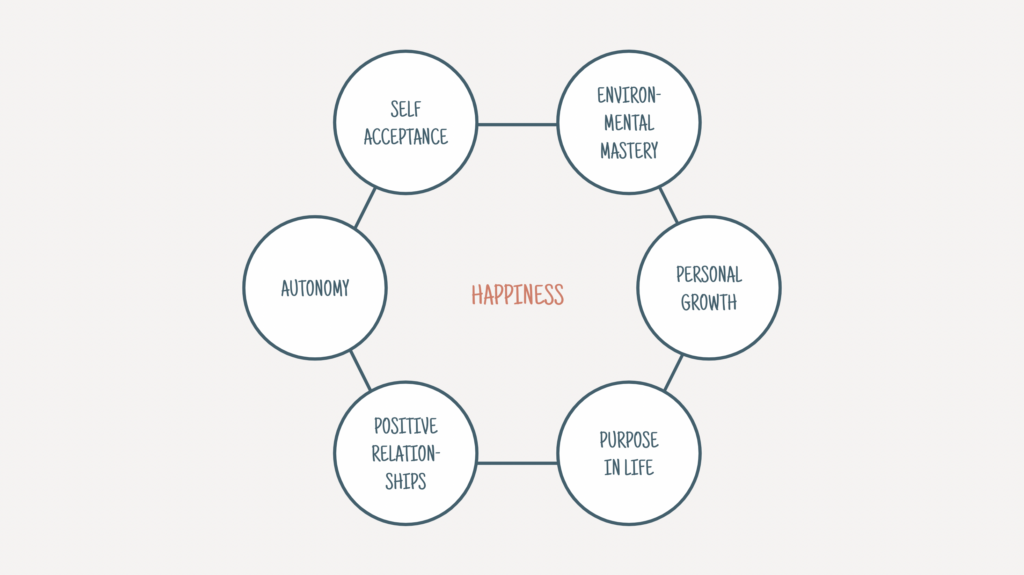

So, for now, it’s psychologists that are leading the dance. Dr Carol Diane Ryff, an American academic and psychologist, has been studying psychological well-being and psychological resilience for decades. Based on her research, she created the Six-factor Model of Psychological Well-being, a theory that outlines the key factors to our happiness.

- Self-acceptance: this is about acknowledging and accepting all aspects of yourself, the good and the bad. It’s being aware of your strengths and weaknesses, and trying to be realistic in the way you assess your own skills and talents. It’s the daily work of loving yourself despite your mistakes and imperfections.

- Autonomy: being independent in the way you think, and having confidence in your opinions despite social pressures. It indicates that you are able to make your own choices.

- Environmental mastery: this means you are feeling in charge. You are able to use opportunities as they arise to address your personal needs. You can manage external factors and activities in your day-to-day life. It comes with a feeling of being in control of the situation in which you live.

- Personal growth: this is the conscious effort to continue to improve yourself through new experiences and constantly trying to become a better version of yourself.

- Positive relations with others: Friends, family, colleagues—in order to be happy, it’s important to have meaningful relationships with others that include reciprocal empathy, affection, and various levels of intimacy.

- Purpose in life: finally, the model suggests exploring ideas you deeply care about to create significance and value in your life. For some people, this is achieved through religion, but you can create meaning through meaningful work, philosophy, or even human connections.

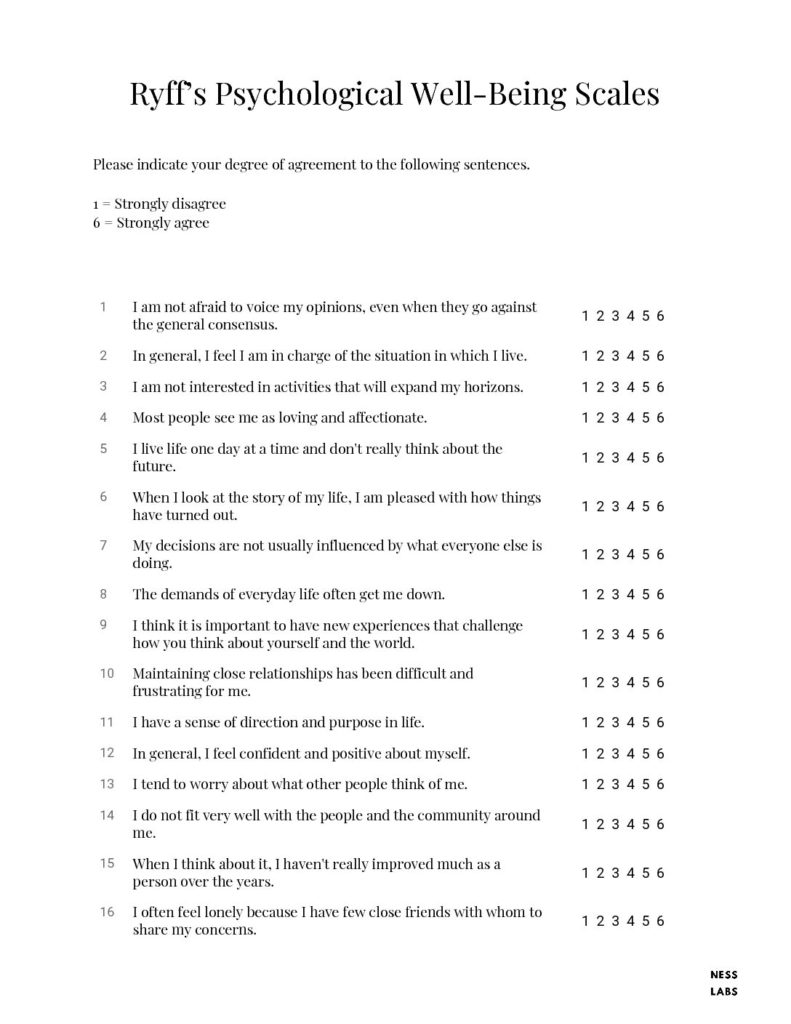

This model was developed into a psychological well-being questionnaire used to measure how happy people are by asking them to rate statements on a scale from 1 to 6.

For example, “I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world” for personal growth, or “I like most aspects of my personality” for self-acceptance. If you would like to take the test, I have uploaded a PDF of the questions and scoring instructions here.

This is all well and good if all you want to measure your happiness, but what about improving it — being happier? Can it been learned?

Teaching and learning happiness

Twenty years ago, Dr Martin Seligman, one of the founders of positive psychology, decided to try to answer this question: can happiness be taught?

In an essay which I strongly recommend reading, he explains how the field of psychology mostly focuses on treating conditions such as depression. How would one go about helping people nurture their positive emotions instead?

He started running a seminar, where he would review the scientific research in positive psychology, and also give students a bit of homework that was quite different from what they were used to.

“When one teaches a traditional seminar on helplessness or depression there is no experiential homework to assign; students can’t very well be told to be depressed or alcoholic for a week. But in Positive Psychology, students can be assigned to make a gratitude visit, or to transform a boring task by using a signature strength, or to give the gift of time to someone they care for.”

Dr Martin Seligman, Psychologist & Author.

His conclusion was that, while happiness itself cannot be taught, we can master the skills that make us happier.

In his seminar, he teaches the skill of disputing unrealistic catastrophic thoughts, the skill of savoring and taking mental photographs, the skill of contemplation, the skill of getting in the flow, or the skill of figuring out your key strengths. “Gratitude is a skill, too little practiced, that amplifies satisfaction about the past,” he says.

He gives students exercises to teach them how to connect to things larger than their own successes and failures. The students learn to mentor younger students. They read Man’s Search for Meaning.

He also notes that school curriculums are not currently designed in a way that teaches students how to live a happy life. While the university you go to has an impact on your salary, it makes no difference to your levels of happiness later in life, as measured by things such as overall life satisfaction, marital happiness, physical wellness, not being depressed, or not being an alcoholic.

This will hopefully change in the future, and it’s amazing to imagine a world where students are taught how to take care of their mental wellness.

In the meantime, though, we are lucky to have this great thing called the Internet, where you can find lots of information to train yourself and acquire the skills needed to live a happier life. I personally write about the topic of happiness in life and at work every week. You can also read the book where Dr Martin Seligman collated all of his findings.