We live in a society where speed has become a measure of performance. We try to quickly go through our to-do lists, keep up with fast-evolving market demands, and rapidly ship product updates.

Sure, we’re productive, in the oldest sense of the term — from Latin producere, which means “to bring forth”. But it somehow doesn’t feel like we are going forth. We dreadfully sense that for all the work we do, we’re not really growing.

We’re stuck in a pointless pursuit, trying to outrun each other and ultimately outrunning ourselves. As a result, the breakneck pace of blind productivity is leaving many people burnt out.

In a 1953 article, famous physicist Samuel Goudsmit already wondered “whether [all the] contrivances physicists have lately rigged up to create energy by accelerating particles of matter [weren’t] playing a wry joke on their inventors. “They are accelerating us too,” he says. In protesting against the speedup, Goudsmit can speak with authority, for in the course of only a few years, he, like many other contemporary physicists, has seen his way of life change from a tranquil one of contemplation to a rat race.”

We could argue that speed is not problematic in and of itself. In fact, many of us find ourselves able to work quite fast on a project when we feel passionate about it — as if wind was blowing through our sails and easily pushing us forward. But it’s because such projects come with a sense of direction.

A mental model for directed growth

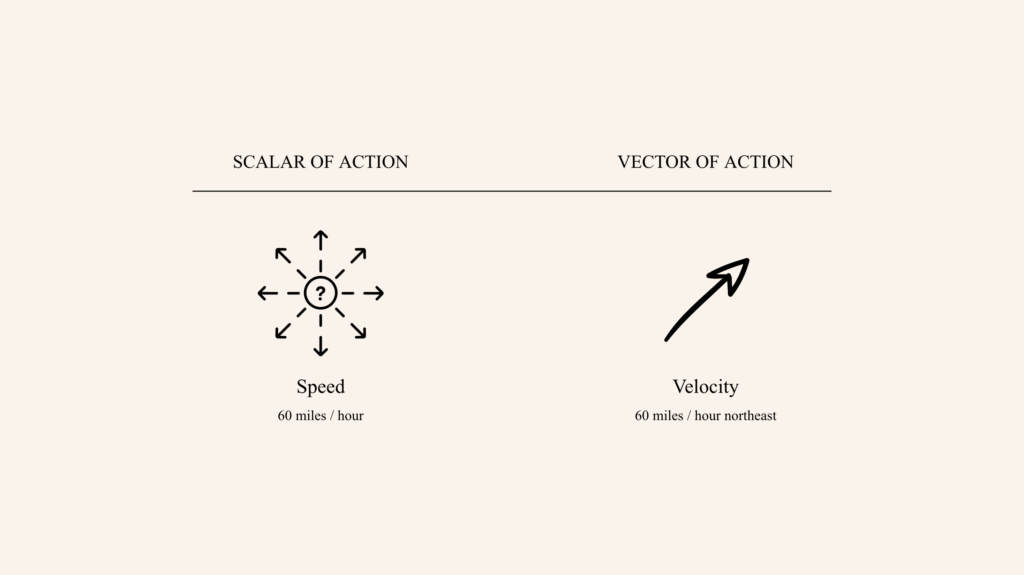

Speed itself doesn’t have direction. When you say that you’re moving at a certain speed (“I’m driving 80 miles per hour”), it doesn’t tell you anything about where you’re going.

This is what mathematicians call a “scalar” — a quantity that can be fully described by its magnitude alone. Speed is a scalar, and so are volume, mass, and time. When you’re talking about how fast or how big something is, you’re describing it as a scalar.

In contrast, a vector is described by both its magnitude and its direction. Velocity is an example of vector: it not only tells you how fast you’re going, but also where you’re going — for instance, “I’m driving 80 miles per hour to the south.”

Thinking about your actions as vectors instead of scalars is a helpful mental model to manage your goals. You’re working a lot (magnitude), but are you learning (direction)? Your team is shipping product updates fast (magnitude), but is customer feedback improving (direction)?

How to design effective vectors of action

Once you understand this mental model, you can consider your vectors of action so it becomes easier to objectively assess your progress, your impact, and your well-being.

- Consider velocity over speed. Remember to not only consider the magnitude of actions — i.e. how fast you’re going, how much work you’re producing — but also the direction of your actions. When considering your actions, think about your trajectory, such as your learning goals, personal growth, opportunities for self-discovery, and wider impact.

- Reflect on your sense of direction. Do you feel like you’re being pulled in different directions? That you’re unclear as to where exactly you — or your team — are going? Or maybe you are going in the right direction, but at the expense of your well-being. Block time to regularly review both your progress and its impact on your emotional and mental health. There is no point making progress if you burn out in the process. Reviewing your external success and your internal experience will help you more sustainable work practices.

- Keep adjusting your trajectory. If you notice that you’re not going anywhere or not going in the right direction, make changes to get on a path that makes sense to you. These changes can be small such as tweaking a workflow or implementing a new routine, or bigger such as exploring a new career or starting a side project. Again, what matters is that these changes improve the direction of your actions.

Vectors of action offer a more holistic view of your progress and whether you’re going in the right direction. Seeing your actions as a vector and not a scalar is a simple mental model to reflect and make adjustments to the way you work, so you can maximize personal growth without sacrificing your mental health. In the words of Dr. Scott Barry Kaufman: “Growth is a direction, not a destination.”