Most people feel that, within the constraints they need to navigate, they are in control of their decisions. But we often automatically follow a train of thought or an external cue without noticing the selective factors in our attention. This phenomenon is called the attentional bias, and it affects many of the decisions we make.

When our unconscious takes the lead

The attentional bias can be defined as our tendency to focus on certain elements while ignoring others. Jonathan Baron, Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, explains: “Attentional bias can be understood as failure to look for evidence against an initial possibility, or as failure to consider alternative possibilities.”

Our attention can be biased by external events as well as internal thoughts and emotions. For instance, being hungry may make you pay more attention to food, and holding certain beliefs will skew your thinking towards decisions that are aligned with these beliefs.

A famous example of attentional bias based on external events is found in cigarette smokers. Research using eye-tracking technology shows that, due to their brain’s altered reward system, pay more attention to smoking cues in their environment. That’s partly why a staggering 75% of quitters return to smoking within a year.

We tend to pay more attention to salient information, whether it’s relevant or not. In an experiment, Dr. Jan Smedslund, Professor Emeritus and Specialist in Clinical Psychology, asked a group of nurses to look through a hundred cards representing what they were told were excerpts from the files of a hundred patients.

For each patient, the card indicated whether the symptom was present or absent, and whether the disease was then found to be present or absent. Some patients had symptoms but no disease, others did not have symptoms but had the disease, some others did not have any symptoms nor the disease, etc. The nurses were asked to figure out whether there was a relationship between a particular symptom and a particular disease.

Now, let’s have a look at the table below, which shows the repartition of the cases:

| Disease present | Disease absent | |

| Symptom present | 37 | 17 |

| Symptom absent | 33 | 13 |

Based on this table, Pr. Jonathan Baron points out that it is possible to determine that “a given patient has about a 70% chance of having the disease, whether this patient has the symptom or not.” In other words, “the symptom is useless in determining who has the disease and who does not, in this group of patients.”

And yet, after going through the cards, 85% of the nurses concluded that there was a relationship between the symptom and the disease. Dr. Jan Smedslund concludes that “they tend to depend exclusively on the frequency of true positive cases in judging relationships.”

Pr. Jonathan Baron adds that “many other experiments have supported [the] general conclusion that subjects tend to ignore part of the table. (…) People who have the chance do not inquire about the half of the table to which they do not attend.”

But attentional bias can arise from within our minds as well. In a similar experiment, researchers Richard Nisbett and Lee Ross asked participants the following question: “Does God answer prayers?”

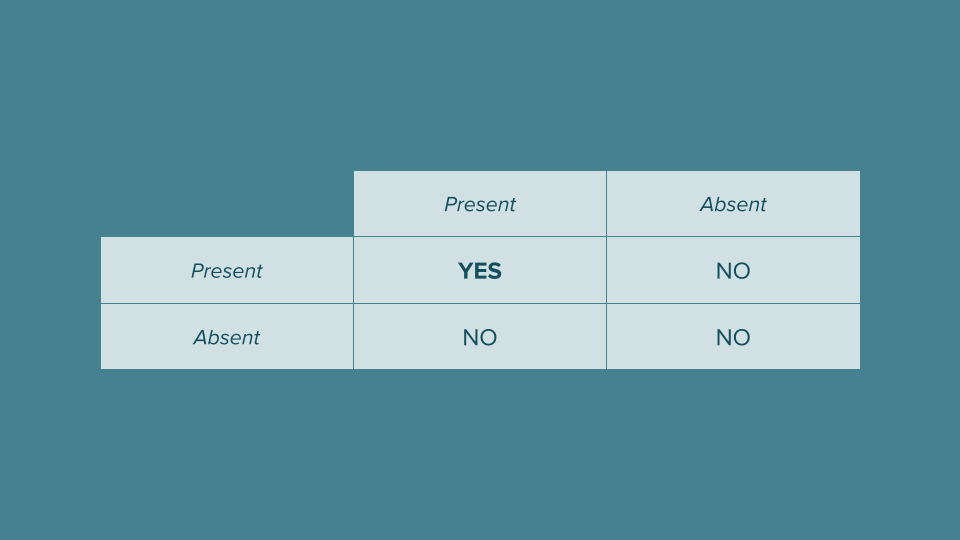

Potential answers can be explored with a similar table:

| Prayer | No prayer | |

| Manifestation | Yes | No |

| No manifestation | No | No |

Again, people who pray will be more likely to answer “yes” to this question, justifying it by saying “many times I’ve asked God for something, and He’s given it to me”, and ignoring the other possibilities. Pr. Jonathan Baron explains: “If you think that God answers your prayers, it stands to reason that some piece of good fortune is a result of prayer.”

However, he doesn’t think attentional bias is a fixed trait. He adds: “Further thinking might involve looking for alternative possibilities (such as the possibility that the good fortune would have occurred anyway) and looking for evidence that might distinguish these possibilities from our favored possibility (what happens when you do not pray). Attentional bias can therefore be correctable by actively open-minded thinking.”

How to manage the attentional bias

While it is impossible to completely get rid of the attentional bias, being aware of the existence of these unconscious processes that act like an invisible puppeteer behind our choices is a first step in reducing their impact on our decision-making. By applying metacognitive strategies to the management of your attention, you can take back control of some of your train of thoughts.

- Pay attention to your attention. Whenever you feel your attention being automatically pulled into a specific direction, ask yourself why this is the case. Is it a particularly salient piece of information, a cue that is linked to a past or current addiction, an answer that perfectly aligns with your existing values and beliefs?

- Go beyond the most obvious answer. If you find the answer to a question completely obvious, chances are some of your thinking is based on heuristics that may not be the only way to approach the problem at hand. Are there any alternative explanations? Did you fail to consider a different point of view? What answer would someone with different pre-existing beliefs give to the same question? You can take notes while you brainstorm, and list all of the alternative explanations you come up with. If you are in a work environment, this exercise also works well as a team.

- Cultivate open-mindedness. None of the previous metacognitive strategies will work if your tunnel vision prevents you from honestly considering the unconscious processes that guide your decisions, and if you are unable to consider alternative ways of thinking. Being open minded is not something you just decide to become. It can be cultivated by asking good questions, reading books outside of your usual interests, and connecting with people who think differently.

Proactively managing your attentional bias requires a bit of effort, but it will make you a better thinker, leading to better decisions and a higher sense of self-awareness. It’s worth giving it a try!