As Einstein wrote in 1936: “All of science is nothing more than the refinement of everyday thinking.” Why is it that a skill as important as thinking is not a key focus in traditional schools? Why don’t we have classes on decision-making, cognitive biases, and mental models? Can we learn how to think better?

It’s a common misconception that brilliant thinkers are born that way, but thinking is a skill which can be practiced just as any other skill. And the good news is: it’s never too late to start proactively applying thinking tools and strategies.

The average human mind is fairly similar across the board. What differentiates between poor thinking and good thinking is the way we decide to use our mind. Lazy shortcuts and cognitive biases will result in poor thinking. Conscious mental models and emotional awareness will result in better thinking.

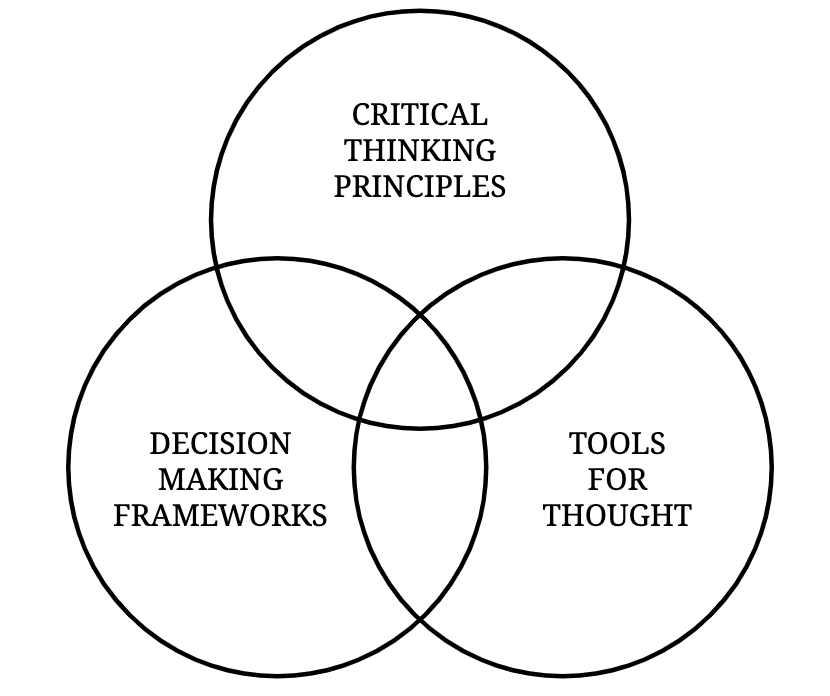

Critically thinking through problems can lead to more efficient solutions. Networked thinking can lead to more creative ideas. Being skeptical of your memories and intuitions can prevent painful mistakes. This guide will explore how to think better with principles, frameworks, and tools for thought.

Table of contents

5 principles to be a better thinker

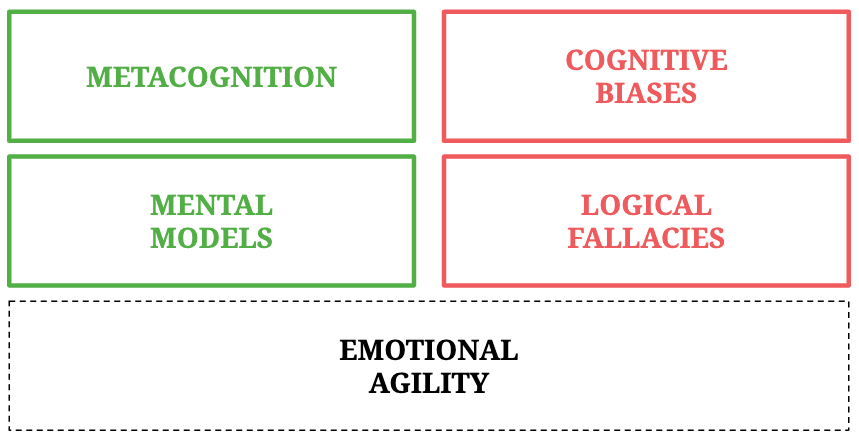

The basics of thinking better are fairly simple. Mainly, they rely on creating healthy thinking habits that encourage us to always question our initial intuitions, to avoid shortcuts, and to consider the second-order consequences of our decisions.

- Think about thinking. Metacognition is the practice of purposeful introspection. Instead of considering the process of thinking as a background operation, metacognitive skills allow people to bring their thought processes to the foreground, so they can be analysed, and potentially improved. Metacognition requires to make space for self-reflection, often in the form of journaling, regular reviews, or working with a thinking buddy.

- Be aware of cognitive biases. The human mind is powerful, but it has limitations. Cognitive biases are systematic errors in thinking that occur when people are processing information. Whether our biases are linked to our memory, our attention, these mental mistakes are often deeply rooted. While it’s hard to always avoid their trap, being aware of our thought processing errors is a first step in managing cognitive biases.

- Avoid linear thinking and logical fallacies. Taking shortcuts when thinking rarely results is the most optimal solution. Second-level thinking is necessary in order to consider the complex ramifications of the decisions we make. As investor Howard Marks puts it: ““First-level thinking is simplistic and superficial, and just about everyone can do it. All the first-level thinker needs is an opinion about the future (…) Second-level thinking is deep, complex and convoluted.”

- Study useful mental models. Some mental models are rooted in biological observations, while others have been described in behavioural studies. They constitute frameworks that give people a representation of how the world works, that guide our thoughts and behaviours and that help us understand life. As a tool that is reflective of the complexities of human nature, mental models need to be used in context, and often in combination. Studying and designing your own mental models is a lifelong learning experience which can lead to better long-term thinking.

- Practice emotional agility. Finally, do not make the mistake of dismissing the influence of emotions on the decision-making process. The rational brain and the emotional brain work in combination: whether you are feeling anxious, stressed, excited, or angry can impact the way you think. Emotional agility encourages you to observe your inner world and to build resilience. Such a compassionate and honest relationship with your emotions will help in limiting their clouding effect on your judgement.

Improve metacognition and mental models, reduce cognitive biases and logical fallacies, and practice emotional agility. While there is no such thing as perfect thinking, these general principles will help you progressively become a better thinker, or at least notice flaws in your thought processes.

Frameworks for better thinking

Beyond general ways to think better, there are structured frameworks that can be used to make better decisions.

“The more you learn, the more you have a framework that the knowledge fits into.” — Bill Gates.

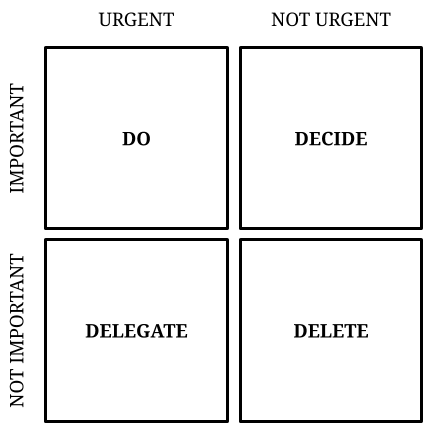

- Eisenhower matrix. Very few decision-making frameworks are as simple and powerful as the 2×2 Eisenhower matrix of prioritisation. First, you make a list of everything you want to do. Then, you categorise them based on the following criteria: urgent and important, important but not urgent, urgent but not important, neither urgent nor important. The categories determine whether you should prioritise, delay, delegate, or remove a task from your list.

- DECIDE framework. The DECIDE framework is incredibly simple to memorise and to apply: define the problem, establish the criteria, consider the alternatives, identify the best alternative, develop and implement a plan of action, and finally, evaluate the solution. Because it carefully evaluates the alternatives and the selected solution, it helps avoid first-level thinking and linear decision-making.

- NASA risk matrix. NASA is known to have a process for everything. The NASA Risk Matrix—also called risk scorecard—helps determine the level of risk associated with a particular situation, and decide how to react.

- Systematic inventive thinking. Using subtraction, multiplication, division, task unification, and attribute dependency, systematic inventive thinking builds an innovation equation to help you think not outside, but inside the box.

- Validity and reliability matrix. Are your mental models accurate? Are they consistent? This 2×2 matrix looks at the validity and reliability of mental models so you can make sure you are using the right mental models for the appropriate situation, and that you can trust to obtain similar results when using the same mental models repeatedly.

- Pre-mortem. In the case of complex projects, anticipate failure with prospective hindsight by performing a pre-mortem. The exercise consists in imagining that a project has failed, and working backward to determine what could have led to the failure.

As with all frameworks, they are not universal, and need to be applied based on the context, the particular challenge, and the goal we want to achieve. Some of these frameworks are quick and easy to use, such as the Eisenhower matrix which can help clean up a to-do list, whereas others are more involved, such as a pre-mortem. Pick the most appropriate frameworks for the job, and feel free to tweak them so they work for your particular use case.

Tools for thought

In order to make the most of these strategies and frameworks, you may want to consider using some tools for thought, which can help consolidate your mental models and serve as a platform for self-education and self-reflection.

- Note-taking apps. I personally use Roam, which has many alternatives, but you could use any note-taking app that fits your note-taking style. While gardeners enjoy apps with bi-directional links and knowledge graphs, architects like more structured note-taking systems such as Notion, and librarians tend to value a simple system to easily store and retrieve their notes such as Evernote. Whatever you choose, a note-taking app is a great tool to build a scaffolding system around your thoughts and to learn how to think better. You can use it for journaling, tracking tasks, brainstorming, doing research, and mapping decisions.

- Digital gardens. To cultivate your thoughts over the long term and benefit from the input of fellow thinkers, you may want to build a digital garden where you can plant seeds of ideas, connect thoughts together, and gradually implement feedback from others or your own new discoveries. Here is my own digital garden, with more examples in this article.

- Spaced repetition softwares. There is no point reading about cognitive biases and mental models if you forget them as soon as you move on. In a sea of unproven learning strategies, spaced repetition is the strongest evidence-based technique to remember anything. Some note-taking apps have a spaced repetition system embedded in the platform. If not, you can use popular apps such as Anki and SuperMemo.

- Mapping tools. Whether you create mind maps or concept maps, visual graphs are a great way to consolidate your thinking. While there are some cool apps, you don’t need anything fancy to start thinking in maps; pen and paper will do. However, if you do want a more powerful too, my favourite one is Scapple (by the same developers as the writing tool Scrivener). I used it to create this mental map.

- Online communities. Another form of scaffolding for the mind is online communities (any form of community of curious minds will do, but the online aspect ensures people are always available whenever you need to discuss your thinking). For instance, Ness Labs offers a private community with online forums and regular virtual meetups, featuring conversations about the human mind. There are many communities around the web that can be used to tackle specific challenges with the help of like-minded people. Some other communities where people come to think together include Change My View, LessWrong, The InterIntellect, the Skeptics Stack Exchange, the Psychology & Neuroscience Stack Exchange, the r/philosophy subreddit, and the Foundation for Critical Thinking community.

Ultimately, the process itself of learning how to think better requires hard work, but it can be fun and fulfilling. Identifying your cognitive biases, deciding which mental models to apply, and having thought-provoking conversations with fellow curious minds is an enriching experience, where the journey matters more than the destination. Good thinking is the result of deliberate practice. So take your time, and fail like a scientist. Good thinking is a precious skill it is worth investing in.